The litany of shorter work week prophecy is prodigious. Keynes famously predicted a 15-hour work week for “our grandchildren” in 1930. Fifteen years later, in a letter to T.S. Eliot, Keynes parenthetically suggested a 35-hour work week for the U.S. in the immediate post-war period. In 1961, Clyde Dankert cited a New York Times article from 1949 in which a “well known labor economist” predicted a 20-hour work week by 1990 and a ten hour week by 2050. Eight years later, a vocational educator forecast the 20-hour week by 2000. Also in 1961, Dankert himself suggested 1980 as the year by which, “the thirty-hour workweek should be widely established and some progress made toward the twenty-five-hour week.” Three years later, he was somewhat more circumspect, “In time we should reach the 30-hour week and even the 25-hour week, but despite all the talk about the leisure society, that time is not now and will not be for quite some years. In a 1957 newsletter, First National City Bank of New York calculated that it would take 31 years to achieve a 32-hour work week if productivity increased at an average of between two and three percent a year and if workers chose to take the benefits in the same proportions of wages and hours as they had from 1909 to 1941.

Topics:

Sandwichman considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

The litany of shorter work week prophecy is prodigious. Keynes famously predicted a 15-hour work week for “our grandchildren” in 1930. Fifteen years later, in a letter to T.S. Eliot, Keynes parenthetically suggested a 35-hour work week for the U.S. in the immediate post-war period.

In 1961, Clyde Dankert cited a New York Times article from 1949 in which a “well known labor economist” predicted a 20-hour work week by 1990 and a ten hour week by 2050. Eight years later, a vocational educator forecast the 20-hour week by 2000. Also in 1961, Dankert himself suggested 1980 as the year by which, “the thirty-hour workweek should be widely established and some progress made toward the twenty-five-hour week.” Three years later, he was somewhat more circumspect, “In time we should reach the 30-hour week and even the 25-hour week, but despite all the talk about the leisure society, that time is not now and will not be for quite some years.

In a 1957 newsletter, First National City Bank of New York calculated that it would take 31 years to achieve a 32-hour work week if productivity increased at an average of between two and three percent a year and if workers chose to take the benefits in the same proportions of wages and hours as they had from 1909 to 1941. Alternatively, a four-day work week could be attained in eight years if productivity gains were applied exclusively to work time reduction. A similar calculation had been made by Fortune editor, Daniel Seligman in 1954:

A calculation made by Fortune for the years since 1929 suggests that in the past quarter-century U.S. workers have been taking about 60 per cent of the productivity pie in the form of income, about 40 per cent as leisure. Assuming that the four-day week for non-agricultural employees will be attained when the total work week is in the vicinity of 32 hours, that productivity continues to increase at an average of 2 or 3 per cent a year, and that something on the order of the recent 60-40 ratio for income and leisure continues in effect, the 32-hour week should be spread throughout the whole non-farm economy in about 25 years.

As did the City Bank forecast, Seligman noted that the shorter work week could be achieved even sooner if workers were willing to forego wage increases.

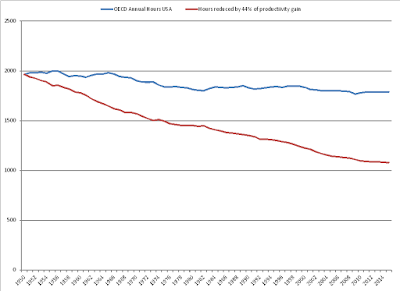

In fact, productivity gains from 1954 to 1979 averaged 2.4 percent per year. From 1957 to 1988, annual productivity gains averaged 2.2 percent. Assuming 40 percent of actual historical productivity gains, ten paid holidays, and four weeks annual vacation, a 32-hour workweek should have been realized by around 1990 — aside from the likelihood that progressive reduction of the hours of work would have accelerated productivity gains.

Using the same assumptions, the work week in 2016 should be around 26 hours. Or perhaps people would prefer to continue with the 32-hour week and take three months annual vacation. These calculations overlook the fact that reduction of the hours of work had already stagnated in the early post-war period. If we backdate the 40 percent of productivity reduction to 1950, the 32-hour mark could have been reached seven years earlier.

Edward Denison estimated that 10% of historical productivity gains could be attributed directly to hours reduction. The chart below factors in that additional 10% productivity gain and compares actual average annual hours, 1950 – 2015 with potential hours if reduced according to Seligman’s and Denison’s assumptions:

But you can’t have it now. You just can’t. How about a tax cut for the richest, instead?