By Jeff Soplop What Happened to the Political Price for Lying? (Part one of two) James Comey’s recent interview on ABC has resurrected questions about the importance of honesty in public officials. One of the key themes of Comey’s interview, and apparently his soon-to-be-released book, is that Donald Trump is “morally unfit” to be president because, among other things, he lies constantly. Certainly Comey’s statements reflect a broad public despair about how untrustworthy the institution of the presidency is, as shown in the following chart from the Pew Research Center. Figure 1 The level of public trust in government has actually been on a long-term decline over the last half century. And that decline isn’t limited to the presidency. The following chart

Topics:

Dan Crawford considers the following as important: Journalism, politics, Taxes/regulation

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

by Jeff Soplop

What Happened to the Political Price for Lying? (Part one of two)

James Comey’s recent interview on ABC has resurrected questions about the importance of honesty in public officials. One of the key themes of Comey’s interview, and apparently his soon-to-be-released book, is that Donald Trump is “morally unfit” to be president because, among other things, he lies constantly.

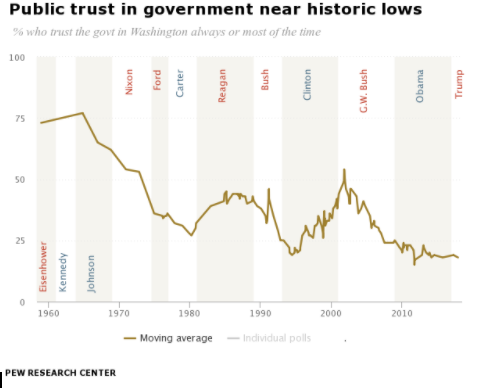

Certainly Comey’s statements reflect a broad public despair about how untrustworthy the institution of the presidency is, as shown in the following chart from the Pew Research Center.

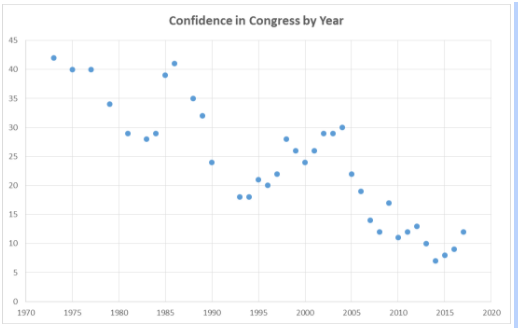

The level of public trust in government has actually been on a long-term decline over the last half century. And that decline isn’t limited to the presidency. The following chart uses data from Gallup to show percent of respondents who say they have a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of trust in Congress by year from 1973.

With the American public holding such little confidence in the federal government, the value of an honest politician seems like it should be at an all-time high. But if that were the case, a politician known to be a consistent liar would pay a heavy price for his duplicity.

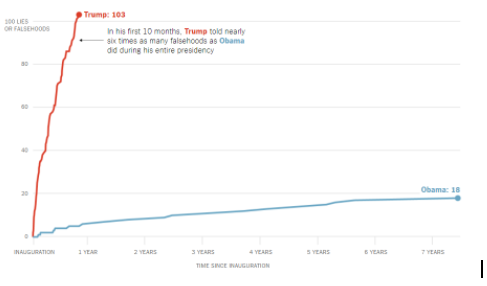

Donald Trump’s election appears to disprove any such premium on honesty or penalty for lying. Take, for example, the following chart from The New York Times benchmarking Trump’s falsehoods to Obama’s.

Or consider the analysis done by PolitiFact that shows only 16% of Trump’s public statements are true or mostly true, with the rest being some type of falsehood. A similar analysis by The Washington Post found that Trump made 1,628 false claims in 298 days for an average of 5.5 (public) lies per day. Objectively, then, Trump is an incredibly dishonest man.

Trump’s dishonesty has been well known and well documented throughout his career and presidential campaign. So only a few possibilities can explain his election; his voters must be either delusional about his dishonesty, they don’t care about honesty, or they do care but not very much.

Starting with the delusional possibility, it seems unlikely that most of the 62,984,825 people who voted for Trump are entirely unable to discern fact from fiction. So while I can’t rule it out, I’m going to move on.

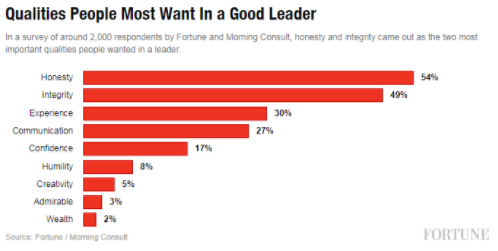

To address whether voters say they care about honesty, we can examine polling data, such as the chart below from Fortune, which shows that honesty is actually the number one quality people say they want in a leader, followed closely by integrity.

In fact, when broken out by political party, the Fortune poll showed that Republicans actually ranked honesty higher, at 57%, than Democrats did at 46%. (On a side note, this data is from 2016 and the most recent I could find. It would be interesting to refresh these poll numbers and see if opinions have shifted since then.)

If voters say honesty is important, and they’re not delusional, the incongruity of electing an inherently dishonest person indicates the voters themselves are not being terribly honest about how much they value honesty.