Some History In 1980, a letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine by the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program stated “the risk of addiction was low when opioids such as oxycodone were prescribed for chronic pain.” It was a brief statement by the doctors conducting the study which was cited many times afterwards as justification for the use of oxycodone. In a June 1, 2017 letter to the NEJM editor, the authors reported on the broad and undocumented assumptions made as a result of the 1980 Letter on the Risk of Opioid Addiction. Using bibliometric analysis of the impact of this letter to the editor, the citations of the 1980 letter were reviewed to determine the citation’s portrayal of the letter’s conclusions. Identified in the

Topics:

run75441 considers the following as important: Healthcare, Hot Topics, Journalism, politics, Recall Report Organization, run75441

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Some History

In 1980, a letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine by the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program stated “the risk of addiction was low when opioids such as oxycodone were prescribed for chronic pain.” It was a brief statement by the doctors conducting the study which was cited many times afterwards as justification for the use of oxycodone.

In a June 1, 2017 letter to the NEJM editor, the authors reported on the broad and undocumented assumptions made as a result of the 1980 Letter on the Risk of Opioid Addiction. Using bibliometric analysis of the impact of this letter to the editor, the citations of the 1980 letter were reviewed to determine the citation’s portrayal of the letter’s conclusions.

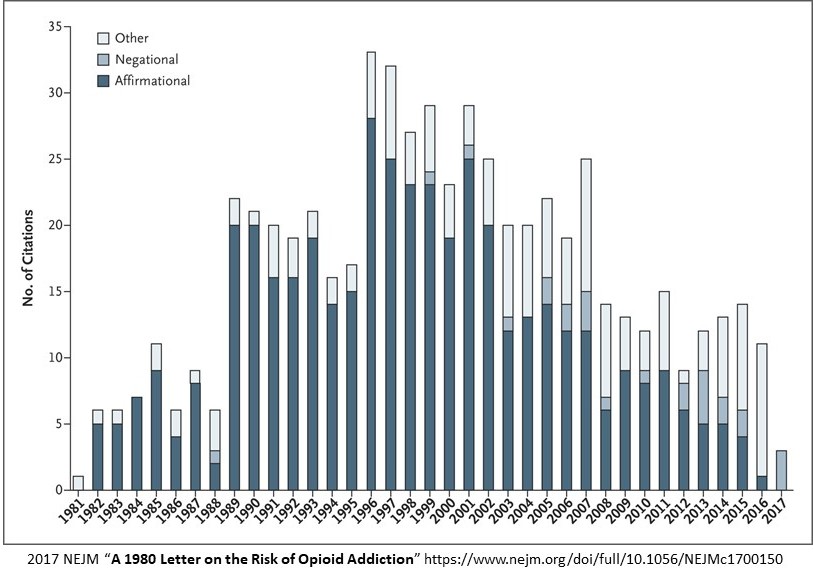

Identified in the bar chart are the number (608) of citations of the 1980 letter over a period of time from 1981 to 2017.

Identified in the bar chart are the number (608) of citations of the 1980 letter over a period of time from 1981 to 2017.

“72.2% (439) cited the letter as evidence addiction was rare in patients when treated with opioids such as oxycodone. 80.8% (491) of the citations failed to note the patients described in the letter were hospitalized at the time they received the prescription.”

There was a sizable increase of citations after the introduction of OxyContin (extended release oxycodone) in 1995. As the analysis noted “affirmational citations of the letter have become less common in recent years in contrast to the 439 (72.2%) positive and supporting citations of the 1980 correspondence in earlier years. The frequency of citation of this 1980 letter stands out as being unusual when compared to other published and cited letters. Eleven other published, stand-alone, and more recent letters on different topics published by the NEJM were cited at a median statistic of 11 times each.

Citations of the 1980 stand alone letter on “addiction being rare” from the use of opioids such as oxycodone failed to mention, the patients administered to were in a hospital setting as noted in the letter by Porter and Jick. Overlooked, a mistake by the people citing this letter? “In 2007, the manufacturer of OxyContin and three senior executives of Purdue Pharma plead guilty to federal criminal charges that they misled regulators, doctors, and patients about the risk of addiction associated with OxyContin.”

![]() Organization: “An early manifestation of the opioid abuse, addiction, and overdose problem occurred largely in the rural regions of Kentucky and other parts of Appalachia after the introduction of Oxycontin. A brand name for oxycodone, OxyContin was introduced in 1996 by Purdue Pharma and aggressively sold to doctors. Sold as a less-addictive alternative to other painkillers as it was made in a time-release formulation, allowing for a slow onset of the drug, and not a hit all at once which is more likely to lead to abuse. When used as prescribed, Oxycontin was safe. When ground up, it’s slow release characteristics were marginalized.

Organization: “An early manifestation of the opioid abuse, addiction, and overdose problem occurred largely in the rural regions of Kentucky and other parts of Appalachia after the introduction of Oxycontin. A brand name for oxycodone, OxyContin was introduced in 1996 by Purdue Pharma and aggressively sold to doctors. Sold as a less-addictive alternative to other painkillers as it was made in a time-release formulation, allowing for a slow onset of the drug, and not a hit all at once which is more likely to lead to abuse. When used as prescribed, Oxycontin was safe. When ground up, it’s slow release characteristics were marginalized.

The aggressive sales pitch led to a spike in prescriptions for OxyContin of which many were for things not requiring a strong painkiller. In 1998, an OxyContin marketing video called “I Got My Life Back,” targeted doctors. In the promotional, a doctor explains opioid painkillers such as OxyContin as being the best pain medicine available, have few if any side effects, and less than 1% of people using them become addicted.

Shortly after 1996, Porter and Jick’s letter citations doubled and continued to be cited in a positive fashion with few negative citations and a failure to mention the hospital setting where the drugs were administered.

More Recently

By 2015 over a six-year period, more than 183,000 deaths from prescription opioids were reported in the United States. Today, millions of Americans are now addicted to opioids.” In part much of this was the result of doctors being told there was a low risk to opioid addiction.

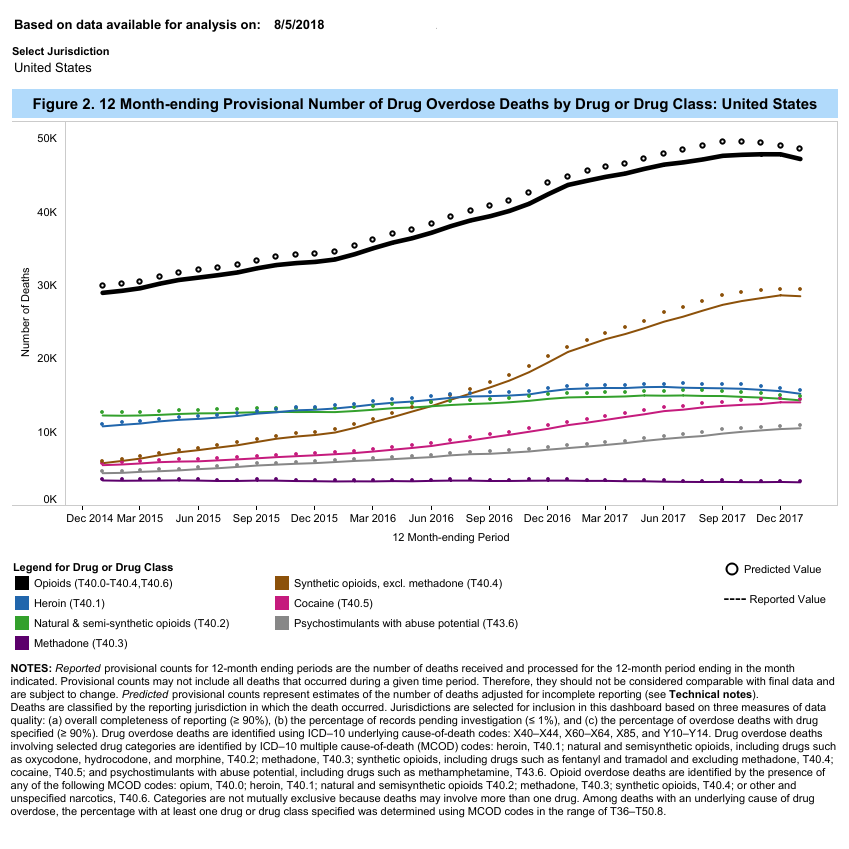

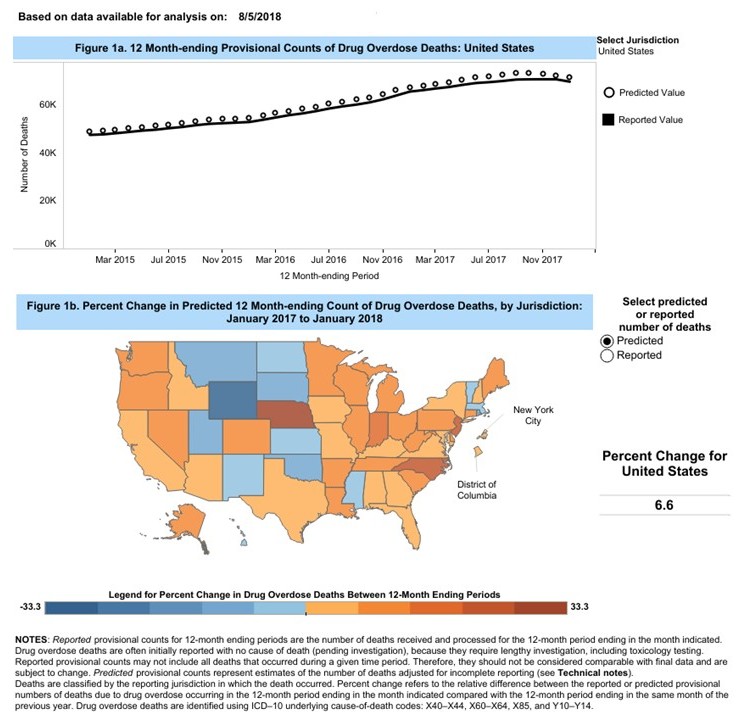

Figure 2 shows each year being progressively worse and reaching a record high of 71,568 deaths (2017) in the US due to all drug overdoses as reported by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in their “Provisional* estimates on U.S. drug overdose. According to the CDC this is a record and represents a 6.6% national increase in overdose deaths over 2016.

At the end of the 12-month period of January 2018, the reported deaths was 69,703. The final and predicted number of deaths is expected to be as high as 71,568. 0.18 of 1% of the reports are pending the completion of investigation (numeric within chart). *Underreported due to incomplete data.

*Provisional counts of all drug overdose deaths are underestimated relative to final counts. The degree of underestimation is determined primarily by the percentage of records with the manner of death reported as “pending investigation” and tends to vary by reporting jurisdiction, year, and month of death. Specifically, the number of drug overdose deaths will be underestimated to a larger extent in jurisdictions with higher percentages of records reported as “pending investigation,” and this percentage tends to be higher in more recent months”.

*Provisional counts of all drug overdose deaths are underestimated relative to final counts. The degree of underestimation is determined primarily by the percentage of records with the manner of death reported as “pending investigation” and tends to vary by reporting jurisdiction, year, and month of death. Specifically, the number of drug overdose deaths will be underestimated to a larger extent in jurisdictions with higher percentages of records reported as “pending investigation,” and this percentage tends to be higher in more recent months”.

In 2018 law makers questioned Miami-Luken and H.D. Smith wanting to know why millions of hydrocodone and oxycodone pills were sent (2006 to 2016) to five pharmacies in four tiny West Virginia towns having a total population of about 22,000. Ten million pills were shipped to two small pharmacies in Williamson, West Virginia. The number of deaths increased along with the company and wholesaler profits.

For context, the nearly 72,000 drug overdose deaths (spurred by the ongoing opioid painkiller addiction epidemic, including the increased use of more potent synthetic opioids [fentanyl]) outpaced fatalities from suicide, or from influenza and pneumonia, which claimed about 44,000 and 57,000 lives in 2016. It nearly rivaled the approximately 79,500 people who die from diabetes-related complications each year in the U.S. (the 7th leading cause of death).

Nearly 150,000 Americans die each year from accidents such as car crashes, injuries, or accidental overdoses. If the CDC’s latest figures are accurate, drug overdoses could account for nearly half of accidental deaths.

As tends to happen with public health epidemics, overdoses have an outsize effect in certain regions. For instance, the biggest spike in fatalities by percentage occurred in Nebraska, North Carolina, New Jersey, Indiana, and West Virginia (33.3%, 22.5%, 21.1%, 15.1%, and 11.2% rises, respectively). But areas like Wyoming, Utah, and Oklahoma experienced declines of 9.2% to 33%.

As tends to happen with public health epidemics, overdoses have an outsize effect in certain regions. For instance, the biggest spike in fatalities by percentage occurred in Nebraska, North Carolina, New Jersey, Indiana, and West Virginia (33.3%, 22.5%, 21.1%, 15.1%, and 11.2% rises, respectively). But areas like Wyoming, Utah, and Oklahoma experienced declines of 9.2% to 33%.

With the clamp down on opioid prescriptions by doctors due to the abuse, addiction, and overdoses, those addicted to opioids turned elsewhere. Again Recall Report;

“In 2015 heroin overdose deaths in the U.S. surpassed the number of deaths by gun homicide for the first time ever. In addiction treatment facilities around the country, heroin addiction is becoming the most common reason to enter treatment, surpassing even alcohol addiction.

In combatting the prescription painkiller addiction epidemic, public officials may have unwittingly contributed to the heroin epidemic. As prescription opioids became more difficult to obtain and more expensive, addicts turned to a cheaper similar high: “heroin.” Mexican drug cartels were more than willing to supply the demand and much of the cheap heroin in use in the country now comes through Mexico.”

The ease of accidentally overdosing can have a tragic consequence resulting from the abuse of opioids and heroin as they act upon areas of the brain controlling breathing by depressing it. Too much of an opioid drug can result in a person stopping breathing and their death. Add alcohol or a sedative and the risk increases. The advent of Narcon in an injection or a nasal spray format is an antagonist to the effects of opioids and heroin heroically reversing the effect of an overdose.

Stopping the abuse of opioids is an important measure in gaining control of the growing number of people becoming addicted to opioids and dying from its abuse. Once addicted, in many cases treatment is essential with detox and withdrawal the first painful step back to a normal life. Without supervised treatment and/or residing in a residential treatment center, the return to opioid usage and addiction is easy as the cravings for using it again are powerful. As a resident in a treatment center, therapy, support, and medical treatment with drugs is possible. The abuse of opioids and addiction will remain a problem for years to come until the supply of it is brought under control.

Prescription Painkiller Addiction: A Gateway to Heroin Addiction, Recall Report Organization

A 1980 Letter on the Risk of Opioid Addiction, NEJM, June 1, 2017

Supplementary Appendix NEJM, June 1, 2017; Copy of Porter and Jick’s letter to NEJM in 1980.

Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts CDC, National Center for Health Statistics, August 5, 2018