Steve Hutkins authors Save the Post Office on issues affecting the Post Office. First, a disclaimer. The following analysis is largely speculative. It’s not based on insider information. The evidence comes from news articles, government reports, legal filings, and a few leaked internal USPS documents that were published on postal news sites. The analysis could be totally wrong. The hypothesis is simply this: The Postal Service has embarked on a plan to reduce labor costs by about 7 percent. That represents approximately 67 million workhours, or the equivalent of about 33,000 jobs. The analysis will also suggest that all the things we saw earlier this summer — the removal of blue collection boxes, the decommissioning of over 700 sorting machines, trucks

Topics:

run75441 considers the following as important: Hot Topics, politics, Steve Hutkins, USPS

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Steve Hutkins authors Save the Post Office on issues affecting the Post Office.

Steve Hutkins authors Save the Post Office on issues affecting the Post Office.

First, a disclaimer. The following analysis is largely speculative. It’s not based on insider information. The evidence comes from news articles, government reports, legal filings, and a few leaked internal USPS documents that were published on postal news sites. The analysis could be totally wrong.

The hypothesis is simply this: The Postal Service has embarked on a plan to reduce labor costs by about 7 percent. That represents approximately 67 million workhours, or the equivalent of about 33,000 jobs.

The analysis will also suggest that all the things we saw earlier this summer — the removal of blue collection boxes, the decommissioning of over 700 sorting machines, trucks leaving plants partially loaded or empty, letter carriers heading out on their routes with mail left behind, a presentation saying that overtime was being eliminated, post offices closing for lunch or earlier in the day, rumors of post offices closing completely — were not, as the Postal Service claimed, isolated incidents, business as usual, or the result of miscommunication between headquarters and local managers.

Rather, they were part of a comprehensive plan to eliminate tens of millions of workhours and downsize the Postal Service in significant ways.

The Seven-Percent Solution

According to its 10-K financial report, in FY 2019 the Postal Service experienced a total “controllable” loss of $3.4 billion. That doesn’t include another $5 billion or so in losses related to pension and retiree health care costs that the Postal Service didn’t pay.

To balance the books, the Postal Service can increase revenues, raise prices or cut costs. Revenue increases are difficult, since First Class letter volumes are falling and Congress has limited what new forms of business the Postal Service can expand into.

The Postal Service has already introduced a temporary rate increase on commercial parcels through the holidays, and it will raise rates again next year. But price increases on letters and flats are limited by law and increases on parcels are constrained by competition in the marketplace. In the past, increasing rates has basically helped the Postal Service keep up with rising costs but done little to reduce the losses.

That leaves cutting costs as the only way to make significant inroads. Given that nearly 80 percent of the Postal Service’s expenses are related to labor, cost cutting means one thing, reducing workhours.

In FY 2019, compensation and benefits costs totaled $47.5 billion. To offset a loss of $3.4 billion, the Postal Service would need to reduce these costs by about 7 percent.

Back in July, District Managers and Plant Managers around the country began sharing Standup Talks in which they outlined the downsizing plan to employees. The talks identify exactly how many workhours need to be eliminated in each district in the three areas of postal operations: mail processing, delivery, and post offices.

The talks indicate that there is a comprehensive plan to reduce workhours across the board by about 7 percent. Even though it hasn’t been stated outright, that goal appears to be a key element of the Postmaster General’s transformative plan for the Postal Service.

The blame game

The Standup Talks on workhours were first made public in mid-July, but their significance was overshadowed by two other documents that were leaked at about the same time.

The first of these was entitled “Mandatory Stand-Up Talk: All Employees. Pivoting to Our Future. July 10, 2020.” This talk focused on reducing transportation costs by eliminating late and extra trips of trucks departing mail processing centers. It apparently led to trucks going off partly filled or even empty, with mail piling up at plants for the next day or later in the week. It was one of the main causes for the mail delays we saw in July and August.

The second document was what appears to be a PowerPoint presentation entitled “PMGs Expectations and Plan.” The slides in the presentation spelled out these expectations: overtime will be eliminated; if plants run late, the mail will be left behind; post offices with windows open more than 8 hours will close for lunch; carrier routes will have no more than four park points, workers comp cases will be closely examined, and so on. “Things will change,” warned the final slide, “and we need to stop thinking like we did decades ago.” (A transcription of the slides is here.)

Both of these documents were widely cited in news articles and quoted by members of Congress in two hearings about the delayed mail. They have also become evidence in several lawsuits against the Postal Service concerning the delays and the threat to voting by mail in November.

Not surprisingly, the Postal Service has tried to distance itself from the documents. The Postmaster General, for example, told Congress he never gave an order to eliminate overtime.

In testimony submitted in several of the lawsuits against the Postal Service and DeJoy, USPS Vice President Angela Curtis explained the confusion: “These documents purport to discuss issues relating to late and extra truck trips, overtime park points, and other topics. These documents were prepared by local managers and were not reviewed or approved by Headquarters. They were distributed locally, not nationally. They do not represent official Postal Service guidance or direction.”

In an article in Government Executive a couple of days ago, Eric Katz took note of the blame game postal executives have been playing to address the problems they created. In their testimonies in the lawsuits, postal officials have essentially said “reforms implemented by Postmaster General Louis DeJoy were never intended to delay mail . . . and would not have caused any mail to be left behind if not for the problems at the local level.”

The problems we’ve been witnessing, they say, were caused by the “poor judgment” of local supervisors, “ineffective management” at a number of facilities, and “workforce performance” problems.

Postal Headquarters will have a more difficult time distancing itself from the Standup Talks about reducing workhours. In fact, these talks suggest that the local managers responsible for those other two documents may have been taking their cues from higher up. The local managers who tried to implement the plans from above may have simply gotten out ahead of things, and now they’re being blamed for it.

As you may have heard

As of today, four versions of the Standup Talk on workhours have been made public. They are each the same, word for word, except for the specific number of workhours that will be reduced in each district. The fact that the talks are identical means, of course, that they were not composed at the district level. They came from L’Enfant Plaza.

It’s not likely that these are the only four districts where these talks were given. It’s a good bet that there are 63 other versions of the talk, one for each of the 67 USPS districts. If that’s true, it’s only a matter of time before more versions surface. They may eventually be subpoenaed in one or more of the lawsuits against the Postal Service.

The first of the workhour talks to become public was entitled “Ohio Valley District Standup Talk.” It’s not clear when it was given, but the text of the talk appeared in PostalNews.com on July 14. The next day, an image of the talk appeared in Postal Times, and one could see who signed off on it — James Shaffer, plant manager of the Columbus P&DC, and Jean Lovejoy, the Ohio Valley District Manager.

Postal Times also included images of the first page of two other versions of the talk, one delivered in the South Jersey District and another in the Central Pennsylvania District. A fourth version, for the Appalachian District, showed up later on Twitter.

The talks all begin the same way:

“Good morning. As you may have heard, the US Postal Service is facing unprecedented financial challenges. Volume has dropped to levels we haven’t experienced for over 30 years all while deliveries continue to grow… As a result of the dramatic volume loss, we are expected to control our costs and to remain solvent while adjusting to changes in demand for our various product lines. Bottom line, we can no longer operate at a loss.”

The Talks then go into the specific workhour reductions that will take place in each district in each area of operations.

Tasking mail processing

The Ohio Valley Standup Talk states: “Mail Processing has been tasked with a reduction of 290,000 workhours. This equates to closing all Plants in Ohio Valley for 20 days or the elimination of one tour from all Mail Processing facilities for 61 days.”

The talk doesn’t indicate what percentage of total workhours this represents, but if one figures plants operate 365 days a year, closing for 20 days represents a reduction of about 5.5 percent.

The Central Pennsylvania Standup Talk says, “Mail Processing has been tasked with a reduction of 148,000 workhours. This equates to closing all Plants in Central Pennsylvania for 15 days or the elimination of one tour from all Mail Processing facilities for 45 days.” That’s a reduction of about 4.1 percent.

The South Jersey District Standup Talk says, “Mail Processing has been tasked with a reduction of 300,000 workhours. This equates to closing all Plants in South Jersey for 34 days or the elimination of one tour from all Mail Processing facilities for 101 days.” That’s a reduction of about 9.3 percent.

The Appalachian District Standup Talk says, “Mail Processing has been tasked with a reduction of 124,000 workhours. This equates to closing all Plants in South Jersey for 29 days or the elimination of one tour from all Mail Processing facilities for 86 days.” That’s a reduction of about 8 percent.

If you average the reductions in these four districts, it comes to about 6.7 percent of total workhours for mail processing.

About those sorting machines

After indicating how many workhours need to be reduced, each of the talks turns to the removal of processing machines. The Ohio Valley talk says, “To work toward this workhour reduction, the district is currently in the process of removing 23 mail processing machines.”

The other talks say the exact same thing, but with different numbers: “To work toward this workhour reduction,” 12 machines in Central Pennsylvania are being removed, 26 machines in South Jersey, and 7 machines in the Appalachian district.

In its motion opposing a preliminary injunction in the Jones v USPS lawsuit, the Postal Service minimizes the significance of the removals: “The USPS has, for years, regularly removed and/or replaced unnecessary mail processing and sorting equipment in its approximately 289 mail processing facilities…. The USPS may also remove machines because they are obsolete; to free up floor space for other needs (e.g., sorting operations or equipment aimed at handling the increased volume of package mail); or as a result of facility consolidations.”

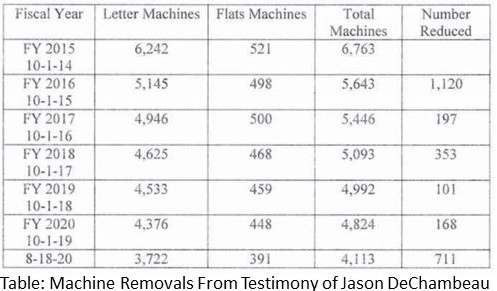

The Postal Service acknowledges that the number of removals this year is unusually high. During the four previous years, a total of 819 machines were removed, about 205 a year. This year, the Postal Service has already removed over 711, and more were set to be removed when the plan was put on pause until after the election.

The total may have approached one thousand (the number in a May 2020 USPS presentation), nearly as many as in 2015, when 1120 machines were removed as part of a large plant consolidation plan that took three years to implement, required slowing delivery service standards, went through a PRC advisory opinion, never cut costs as predicted, and ended up causing significant mail delays (as discussed in this OIG report).

In his testimony about the removals, Jason DeChambeau, USPS Headquarters Director of Processing Operations, explained that the Postal Service has removed unnecessary and outdated machines for years, so there’s nothing unusual about these recent removals. He then goes on to explain how the removals save money:

“Unnecessarily keeping underutilized machines in certain locations is inefficient and costly.” It takes fewer employees to run one machine instead of two; it takes time to set up a machine for a processing period and close it down at the end; fewer machines means lower maintenance costs; a machine running at capacity means more volume per tray and more mail in each truck, and so on.

Removing machines, in other words, reduces workhours. The Postal Service acknowledges this fact in its Jones’ brief and DeChambeau’s testimony, but it does not say that removing the machines is part of a more comprehensive national plan to reduce millions of workhours.

As an aside here, it may be worth noting that the Postal Service could be reducing its mail processing capacity for a related reason. The report of the 2018 Trump Administration Task Force on postal reform contains this recommendation: “Evaluate areas of USPS operations where the USPS could expand third party relationships in order to provide services in a more cost efficient manner (e.g., midstream logistics and processing).”

In other words, the Postal Service may not need all of these sorting machines because it is going to be outsourcing more of this work to the private sector, where labor is cheaper. (The Postmaster General, coincidentally enough, made his fortune in “midstream logistics and processing,” including multi-million dollar no-bid contracts with the Postal Service.)

Tasking city delivery

The Standup Talks next turn to reducing workhours in city delivery. The Ohio Valley Standup says, “City Delivery has been tasked with a reduction of 488,541 workhours. This equates to 18 days of complete non-delivery or the elimination of 6.5% of all city routes (190 city routes) or the reduction of 33 minutes per route per day.”

The Central Pennsylvania Standup Talk, using the exact same language, calls for a reduction equivalent to 6.4 percent of all city routes; in the South Jersey District, it’s 6.5 percent; and in the Appalachian District, it’s 4.9 percent. Overall, the cuts are not far from the 7 percent reduction that seems to be the overall goal.

Eliminating city routes is almost impossible since the number of delivery points is always increasing and carriers are already stretched. Eliminating a day of delivery, like Saturday, has been discussed, but it’s controversial. That leaves trying to cut some time from each carrier’s workday.

That seems to be the goal of the plan Expedited to Street/Afternoon Sortation (ESAS), which reduced morning office time to allow carriers to leave for the street earlier, even if it meant leaving unsorted mail for delivery the next day. This was apparently another cause for mail delays this summer.

The Trump Task Force report recommends a couple of other ways to save on carrier costs. Delivery points can be reduced by using cluster boxes instead of individual mailboxes. This is always a controversial change, as illustrated a few days ago in a “standoff” between residents and the Postal Service in Clarksville, TN.A second way to reduce delivery points is by removing blue collection boxes. That practice has been going on for many years, as the Postal Service and other commentators reminded us when people became alarmed at box removals earlier this summer.

The Trump Task Force report recommends a couple of other ways to save on carrier costs. Delivery points can be reduced by using cluster boxes instead of individual mailboxes. This is always a controversial change, as illustrated a few days ago in a “standoff” between residents and the Postal Service in Clarksville, TN.A second way to reduce delivery points is by removing blue collection boxes. That practice has been going on for many years, as the Postal Service and other commentators reminded us when people became alarmed at box removals earlier this summer.

Just a couple of days ago, Senator Jon Tester of Montana sent another letter to the Postmaster General complaining about the lack of transparency in the box removals and asking for more details about which boxes have been removed and what density tests have been done to determine which boxes to cull.

It’s possible that what happened this summer was not as routine as the Postal Service makes out. It could be that the number of removals was unusually high, or that a change was made in the low-volume threshold that triggers a removal. Tester’s frustration in getting answers contributes to the feeling that there’s something going on, more than meets the eye — like a national plan we’ve yet to see.

Tasking clerk and retail operations

The Standup Talks proceed to address workhour reductions in post offices. The Ohio Valley Talk says the following: “Clerk and Retail Operations have been tasked with a reduction of 129,091 workhours. This equates to no LDC 43 Distribution, no LDC 44 PO Box Distribution and no LDC 48 Admin/Miscellaneous for 18 days (equals 76,449 workhours) plus the window closure of all offices for 21 days or the total window closure across the district for 51 days.”

Those LDC numbers refer to the work that clerks do in the back of the post office. LDC 43 refers to manual distribution of letters, flats, and parcels. LDC 44 refers to distributing mail in Post Office Boxes, etc.

Closing Ohio Valley post office operations in the back and at windows for about 19 days a year represents a workhour reduction of about 7.6 percent.

The Appalachian District is tasked with a reduction of 112,475 workhours, which equates to no work in the back of the office for 13 days, “plus the window closure of all offices for 69 days or the total window closure across the district for 90 days.”

The second page is not available for the other two Talks, but presumably the wording is the same with different numbers.

Workhour reductions of this magnitude will not be easy to accomplish. Skipping back-office sortation a couple of days a month would cause serious backlogs and delays, and closing window services for 51 days or 90 days out of the year is impossible. But the Postal Service can do other things to reduce workhours in its retail network.

It can, for example, simply close a lot of post offices. In the Ohio Valley District, about 190 post offices had their hours reduced under POStPlan (which cut hours at 11,000 small rural offices) to just 2 or 4 hours per day. Closing 120 of these post offices would save about 130,000 workhours. There are about 660 post offices in the Ohio Valley District, so that would mean closing about 18 percent of them. On a national level, it would mean closing about 5,500 small rural post offices. That could prove to be very unpopular.

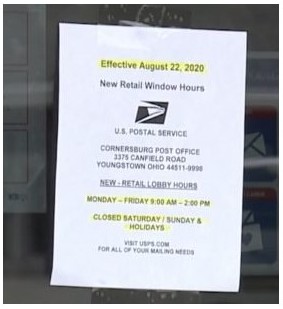

Another approach would be to be to pick up where POStPlan left off and reduce hours at more post offices. That plan was well underway earlier this summer. According to an article in Vice.com, union officials in the South Jersey District were told that 10 offices were dropping from nine hours to four, while another 30 were slated to close during lunch hours, typically among the busiest times of day at a post office. News reports indicated that post offices in Berkeley, California, Petersburg, Alaska, Knoxville, Tennessee, and Youngstown, Ohio, announced similar plans. The Cornersburg Post Office in Youngstown, for example, was set to have its hours reduced from 46 hours per week (Mon-Fri, 8:30-5; Sat, 8:30-12) to 25 hours per week (Mon-Fri, 9-2; closed Sat).

Another approach would be to be to pick up where POStPlan left off and reduce hours at more post offices. That plan was well underway earlier this summer. According to an article in Vice.com, union officials in the South Jersey District were told that 10 offices were dropping from nine hours to four, while another 30 were slated to close during lunch hours, typically among the busiest times of day at a post office. News reports indicated that post offices in Berkeley, California, Petersburg, Alaska, Knoxville, Tennessee, and Youngstown, Ohio, announced similar plans. The Cornersburg Post Office in Youngstown, for example, was set to have its hours reduced from 46 hours per week (Mon-Fri, 8:30-5; Sat, 8:30-12) to 25 hours per week (Mon-Fri, 9-2; closed Sat).

In the Appalachian District at least a dozen offices in W. Virginia were the subject of “feasibility studies” for closure, 26 offices were reducing hours from a full day to four, and another 31 offices were closing during lunch hours. When West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin heard about these plans, he contacted the Postal Service and was told that signs were incorrectly posted in post offices about the pending closure or the new hours because of a “misunderstanding” between District officials and local postmasters.

Manchin wasn’t satisfied with the explanation, and he says the response he got from the Postal Service left him with even more questions: “Where are these post office locations that might be shut down or have their hours reduced? Why were these locations selected? Why wasn’t any of this information included in the letter as I requested?”

Perhaps the Postal Service has not been as forthcoming as it could be because it doesn’t want to explain that these “misunderstandings” were part of a comprehensive plan to close offices and reduce hours across the country, a plan it’s not quite ready to reveal. Before the Postal Service started to close post offices under the Retail Access Optimization Initiative in 2011 and before it reduced hours under POStPlan in 2012, it requested advisory opinions from the Postal Regulatory Commission. It’s hard to understand why the Postal Service thought it could get away with this new plan without doing so again.

Adding things up

After going through the workhour reductions in the three areas of operations, the Standup Talks offer some encouraging words to postal workers: “Being reliable, coming to work and working safely cuts down overtime and unnecessary workhours.”

That phrase about cutting down on overtime may have led to the notion that the Postmaster General was eliminating overtime. The word had apparently gone out that there was going to be a big push to reduce workhours across the country, especially overtime hours.

The Standup Talk continues, “Being dedicated and performing to the best of your ability every minute of every day helps preserve jobs.”

The irony in that comment is that in the long run reducing workhours means eliminating jobs — a lot of them.

The Ohio Valley District Standup Talk says the plan is to reduce 290,000 workhours in mail processing, 488,541 in city delivery, and 129,091 for clerk and retail. That adds up to 907,632 workhours.

If reductions in the 67 districts averaged about 1 million workhours, we’d be looking at about 67 million workhours. At an average cost per hour of about $50 ($30/hour for wages, plus overtime and benefits), eliminating 67 million workhours would save the Postal Service $3.35 billion. As noted above, that’s 7 percent of the total cost of wages and compensation, and it’s almost exactly what the Postal Service lost in operations in FY 2019.

Reducing workhours may make the Postal Service more “efficient” and help it act “more like a business,” but cutting 67 million workhours “equates” to eliminating about 33,000 jobs.

If that’s the Postmaster General’s master plan for transforming the Postal Service, he should come out and say so.

The Seven-Percent Solution: The Not-So-Secret Plan to Downsize the Postal Service, Save the Post Office, Steve Hutkins, September, 14, 2020