Angry Bear has been featuring the words of Steve Hutkins and Mark Jamison for a good bit of time now. They are the go-to people outside of the USPS on issues associated with it and the Congress which impacts it. We exchange emails and stories from time to time. Save the Post Office is edited and administered by Steve Hutkins, a retired English professor who taught place studies and travel literature at the Gallatin School of New York University. Expected Rate Increases Beyond CPI On November 30, 2020, the Postal Regulatory Commission issued a 484-page order revising the rate system for Market Dominant products. Under the new system, the Postal Service will be able to raise rates beyond the Consumer Price Index, which it was prevented from

Topics:

run75441 considers the following as important: law, politics, Save The Post Office, Steve Hutkins, Taxes/regulation, USPS

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Angry Bear has been featuring the words of Steve Hutkins and Mark Jamison for a good bit of time now. They are the go-to people outside of the USPS on issues associated with it and the Congress which impacts it. We exchange emails and stories from time to time.

Save the Post Office is edited and administered by Steve Hutkins, a retired English professor who taught place studies and travel literature at the Gallatin School of New York University.

Expected Rate Increases Beyond CPI

On November 30, 2020, the Postal Regulatory Commission issued a 484-page order revising the rate system for Market Dominant products. Under the new system, the Postal Service will be able to raise rates beyond the Consumer Price Index, which it was prevented from doing (aside from the provision for an exigent increase) by the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act of 2006. (See this previous post for more about the order.)

Last week, the Postal Service gave the PRC its calculations for the two new authorities crafted by the Commission. The Notice of Calculations of Future Rate Authorities indicates that the density-based rate authority will be 4.5 percent, and the retirement-based rate authority will be 1.06 percent, for a total of 5.56 percent.

Those potential increases are on top of the approximately 1.8 percent increase for First-Class Mail and 1.5 percent increase for other categories the Postal Service has already proposed for 2021. If the Postal Service were to exercise its full rate authority, the total increase would thus be over 7 percent. The new system also gives the Postal Service authority for an additional 2 percent increase for products that don’t cover their attributable costs.

The new rate authorities will take some time to go into effect in a price hike, almost certainly not before summer 2021. And it’s very possible that the Postal Service will not take full advantage of its new authority and instead bank some portion for future use.

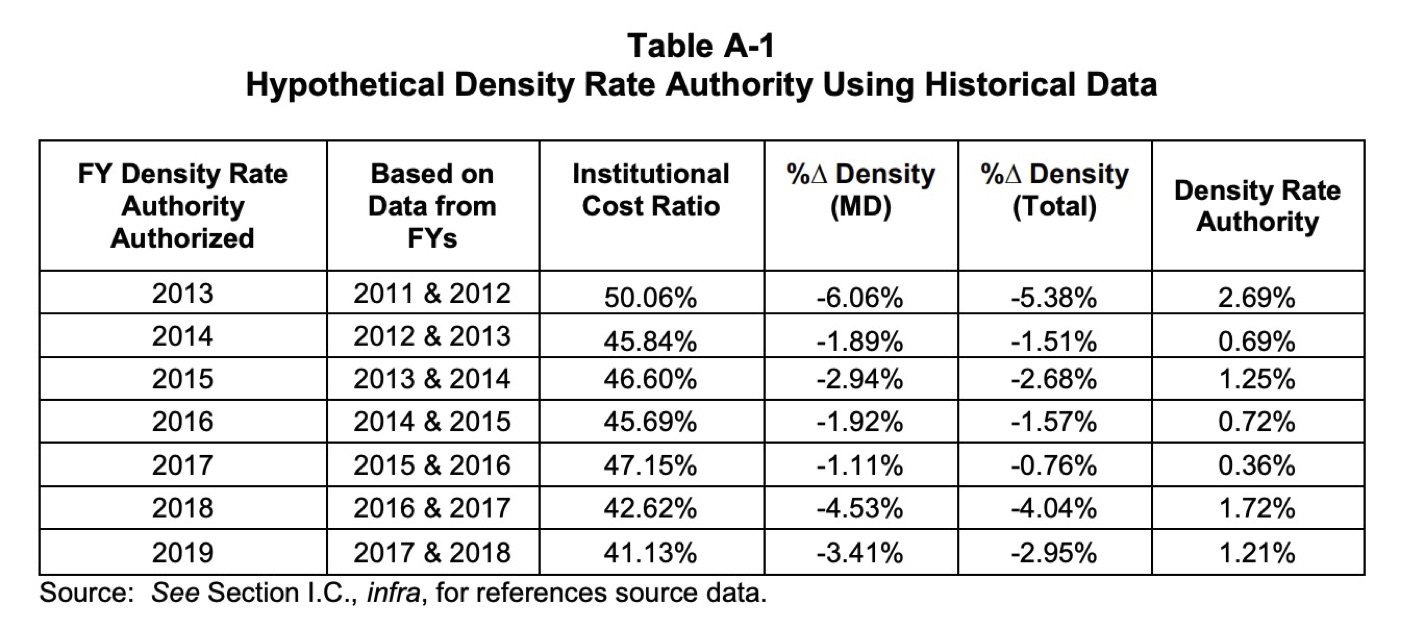

The rate authority numbers presented last week are considerably greater than what the Commission had envisioned over the past couple of years as it was developing the formulas for future above-CPI increases. This table from the order shows what the density-based increases would have been in previous years based on the new formula. The average authority for this period would have been about 1.23 percent annually; the highest was the 2013 number, 2.69 percent.

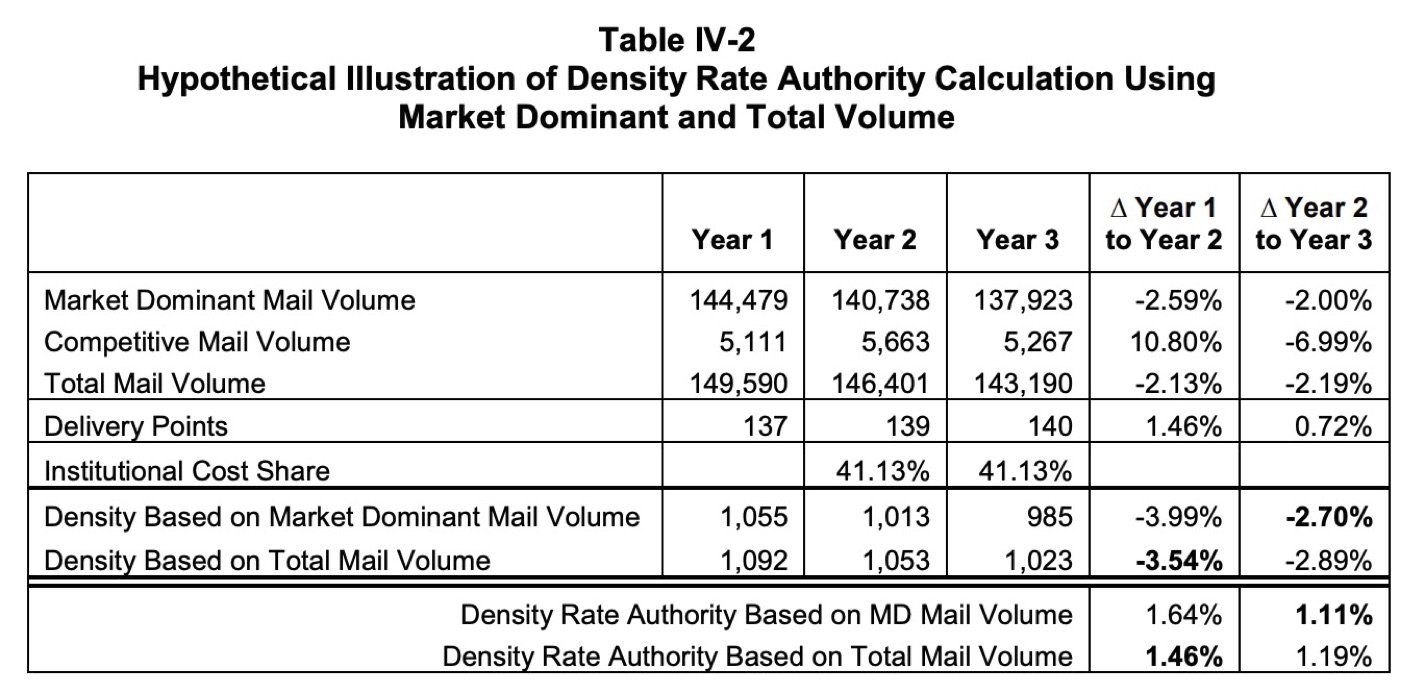

The following table shows the hypothetical calculations for the first two years of the new system. The estimates were presented in a PRC order in December 2019. The numbers correspond roughly to the situation in 2018-2019, when total mail volume fell from 146.4 billion to 142.6 billion.

The calculations produce a density rate authority based on Market Dominant volume and a second based on total mail volume. The system uses the lower of these two calculations, so for hypothetical year 1, the rate authority would be 1.46 percent and for year two, 1.11 percent.

Together the two hypothetical illustrations suggest that the anticipated rate authority for 2020 would have been something on the order of 1.3 percent. But then the pandemic happened.

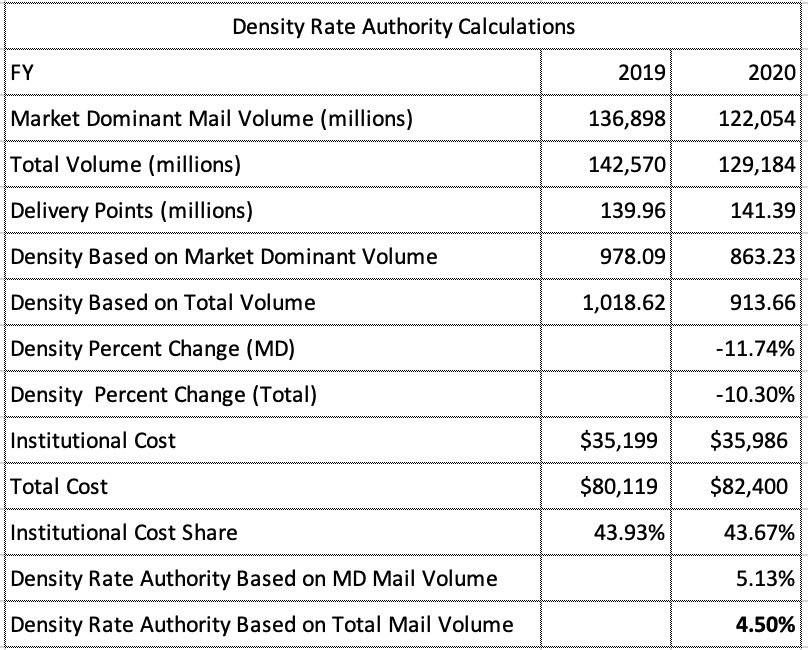

Here’s a table showing the Postal Service’s actual calculations for 2020 submitted last week.

According to these calculations, the density rate authority for 2020 is 4.5 percent. That is about three and half times what the hypothetical examples would have predicted.

The reason for this is simple: The formula for the density rate authority is based primarily on the number of pieces per delivery point. The number of delivery points increased in 2020 by about one million, but this was comparable to previous years and doesn’t explain why the 2020 rate authority is so large. On the other hand, the drop in mail volume was much greater than normal due to the pandemic, and this leads to a much greater density rate authority.

The PRC’s formula, it should be noted, also incorporates the institutional cost shares of Market Dominant and Competitive products. As the PRC’s order (p. 74) explains, “[The formula] permits Market Dominant mailers to benefit from reduced density-based rate authority when Competitive products experience more favorable changes in volume than Market Dominant products.” But even with the unprecedented growth of parcel volumes due to the pandemic, this factor did not have much effect on the density rate authority. The most significant factor is the drop in mail volume.

The recession caused an unusually large annual drop of 12.8 percent in 2009, but since then total mail volume has fallen fairly consistently, about 2.1 percent a year — until 2020.

The drop in 2020 was 9.4 percent, from 142.6 billion pieces to 129.2 billion. That’s well over four times the annual average decrease since 2010.

Most of this decline occurred after the pandemic hit in March. During the first half of FY 2020 (Oct 2019 – March 2020), total volume was 71.8 billion, down from 75.1 billion in 2019, a drop of 4.4 percent. During the second half of 2020, total volume decreased to 57 billion, compared to 67.5 billion in 2019, a decline of 15 percent. The big drop in the second half of the fiscal year is thus responsible for the much larger density rate authority.

The second rate increase authority is based on Congressionally-required amortization payments for retirement health benefit and pension costs. Unlike the density rate authority, this retirement authority cannot be banked. It also could become irrelevant if Congress were to pass legislation that modified how the Postal Service deals with these costs.

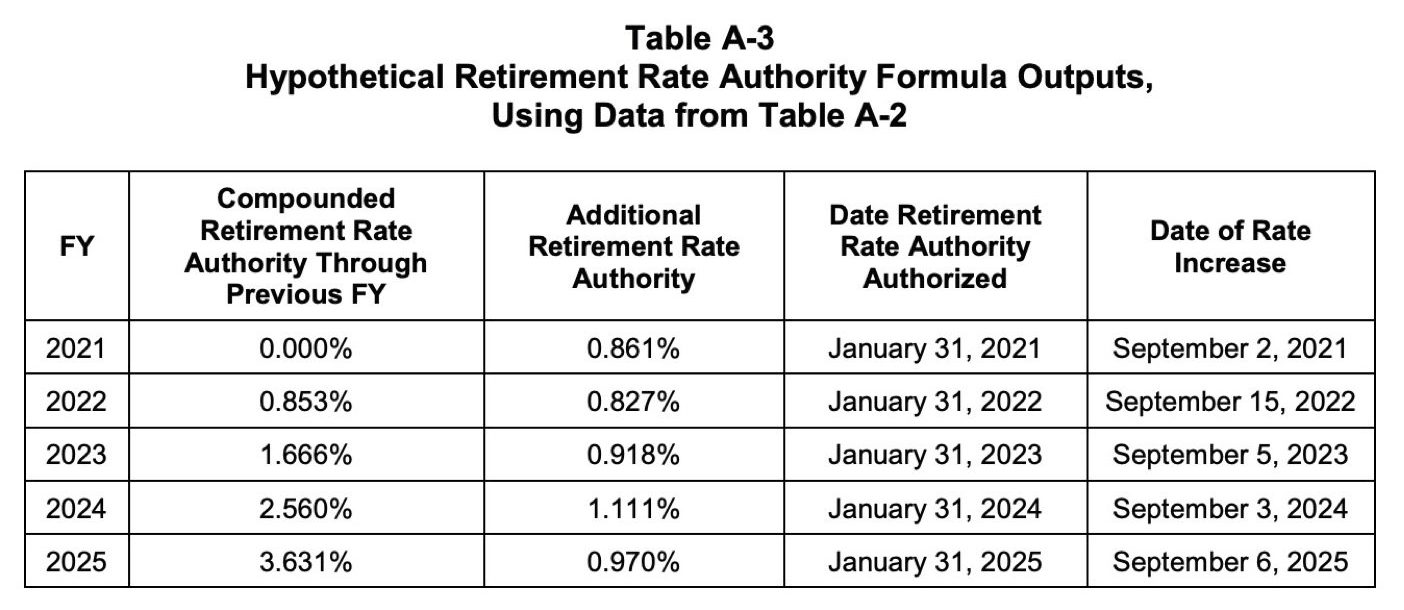

Here’s a table showing what the retirement-based authority was projected to be in the PRC’s order.

The actual calculation for 2020 came out to be 1.06 percent, slightly more than the 0.86 percent that had been projected but within the same ballpark.

The new system also grants the Postal Service an additional 2 percent of rate authority for products considered “non-compensatory,” i.e., the revenue they bring in doesn’t cover their attributable costs. The two products for which this applied in 2020 were Periodicals and Package Services (Alaska Bypass, Media and Library Mail, Bound Printed Flats, etc.).

In its Rate Authority Notice, the Postal Service declares its intention to use the new authority. The USPS is not required to issue a rate notification use it immediately or lose it and can instead bank the unused authority until another time. Under current law, the banking can extend for five years.

“To provide added flexibility,” states the PRC in its order on the new system, “the Commission modifies final §3030.222 such that the Postal Service may use the additional authority to generate unused rate adjustment authority. This change also takes into consideration the assumption that the ability to use the additional authority is equivalent to a requirement. Making the additional authority bankable discourages the Postal Service from simply using it to avoid losing it. Rather, this change provides more incentive for the Postal Service to consider demand, ECSI value, and other market conditions before determining whether to use the additional authority.”

In other words, the Board of Governors may decide that using the full authority might not be advisable. It could, for example, cause rate shock and hurt business, so the Postal Service could use part of the new authority and save some for later.

For these rate authorities to take effect in actual price increases, the Postal Service will not need to wait until the next regular price adjustment, which would delay the above-CPI increases until January 2022. The Commission’s order on the new system states that “the Postal Service retains the flexibility to propose an out-of-sequence price adjustment at any time. The rate authority provided by the final rules is available for the Postal Service to use shortly after the effective date of the rules, and following the Commission’s determination.”

The timing could go something like this. The Commission first needs to validate the Postal Service’s proposed calculations, which are based on numbers in the Annual Compliance Determination. Any additional rate authority would be available to the Postal Service in late March 2021 when the ACD is issued. The Board of Governors would then need to decide, based on this authority and any other factors it wants to consider, what the new prices will be. The Commission then needs to conduct further proceedings reviewing and approving the new rates.

Once approved, the Postal Service must then provide 90 days’ notice before implementing the prices, which would take us to sometime in July or later. (The order on the new rate system extended the minimum notice period between the date the Postal Service files a notice of proposed rate adjustment and the date the proposed rates could go into effect from 45 days to 90 days.)

The process can also be affected by other circumstances. Several of the mailers’ associations have filed two appeals with the D.C. Circuit (they’ll probably be consolidated at some point, but the docket info can be found here and here). These mailers have also filed a motion for a stay with the PRC, requesting that “the Commission stay the effective date of the Orders and related regulations until the petitions for review are resolved by the Court of Appeals.”

The appeals process could take several months, even a year or more. Since 2009, the Postal Service has appealed a PRC order twenty times, and the average duration between the initial filing and the court’s ruling has been 341 days. Several appeals were handled much more expeditiously, but these usually involved relatively simple issues, like unsealing non-public material. The big cases involving rate changes often took more than a year.

That in fact is one of the points the Postal Service makes in the opposition to the motion for a stay that it filed today with the PRC. “There is no guarantee as to how long the court may take to resolve cases filed by multiple parties on an administrative record spanning four years and thousands of pages,” writes the Postal Service. And in a footnote, the Postal Service points out that “in January 2014, the Postal Service and various of the Mailers filed crosspetitions for review of the Commission’s December 2013 order in the so-called exigent case. The court did not issue its decision until seventeen months later.”

Unless the Commission grants the mailers’ motion for a stay, some sort of above-CPI increase could take place mid-2021. And even if the appeal eventually succeeds in getting some sort of order overturning the changes in the rate system or remanding the case back to the PRC, there are no refunds when it comes to postal rates.

—Steve Hutkins, ed.