I broke this report down into two parts, a Part one which is this recital covering natural health outcomes. A Part Two will review a different healthcare perspective or unnatural health outcomes. I broke it into two parts to make it an easier read (duration). I also rewrote parts of this Issue Brief to give it greater clarity. However, it is not a complex read. The charts and graphs enhance its clarity when comparing the US to other countries. The message in the 2022 Global US Healthcare perspective mimics the 2019 Global US Healthcare perspective. Not much has changed for US citizens healthcare. Indeed, one might say, it has worsened. The United States still spends more money on healthcare than other countries and achieves lesser quality

Topics:

run75441 considers the following as important: Education, Global healthcare, Healthcare, US healthcare, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Joel Eissenberg writes How Tesla makes money

Joel Eissenberg writes RFK Jr. blames the victims

Angry Bear writes True pricing: effects on competition

I broke this report down into two parts, a Part one which is this recital covering natural health outcomes. A Part Two will review a different healthcare perspective or unnatural health outcomes. I broke it into two parts to make it an easier read (duration).

I also rewrote parts of this Issue Brief to give it greater clarity. However, it is not a complex read. The charts and graphs enhance its clarity when comparing the US to other countries. The message in the 2022 Global US Healthcare perspective mimics the 2019 Global US Healthcare perspective. Not much has changed for US citizens healthcare. Indeed, one might say, it has worsened.

The United States still spends more money on healthcare than other countries and achieves lesser quality results or outcomes in return. The graphs will help you understand the issues. From reading this, access is an issue. Costs are an issue. Lack of Primary Care doctors and their salary is an issue. And I believe personal care for one’s self plays into this.

U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2022, Commonwealth Fund, Munira Z. Gunja, Evan D. Gumas, and Reginald D. Williams II. January 2023

Introduction

In the previous 2019 edition of U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, Commonwealth Fund reported people in the United States experience the worst health outcomes overall of any high-income nation.1 Americans are more likely to die younger, and from avoidable causes, than residents of peer countries.

Between January 2020 and December 2021, life expectancy dropped in the U.S. and other countries.2 The pandemic being a continuing threat to global health and well-being. Commonwealth Fund has updated its 2019 cross-national comparison of health care systems again to assess U.S. health spending, outcomes, status, and service use relative to Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. It also compares U.S. health system performance to the OECD average for the 38 high-income countries for which data are available. The data for the Commonwealth Fund analysis comes from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and other international sources (“How We Conducted This Study).”

For every metric it examines, the latest data available is used. This means the results for certain countries may reflect the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when mental health conditions were surging, essential health services were disrupted, and patients may not have received the same level of care.3

Highlights

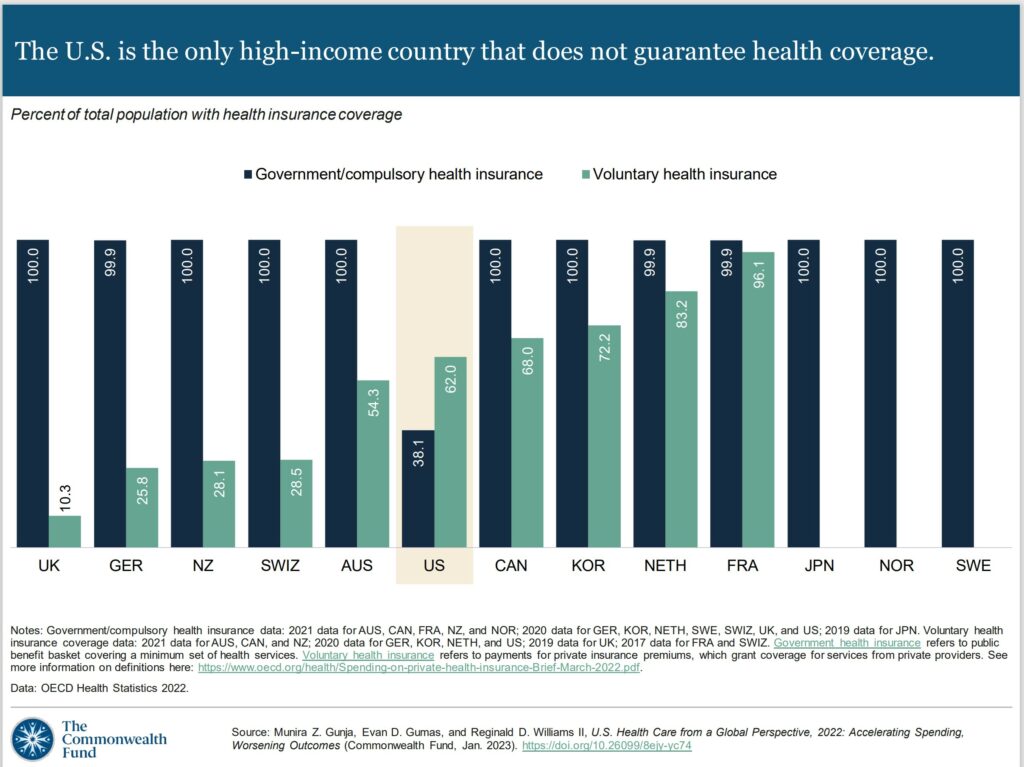

- Health care spending, both per person as a share of GDP, continues to be far higher in the United States than in other high-income countries. Yet, the U.S. is the only country not having universal health coverage.

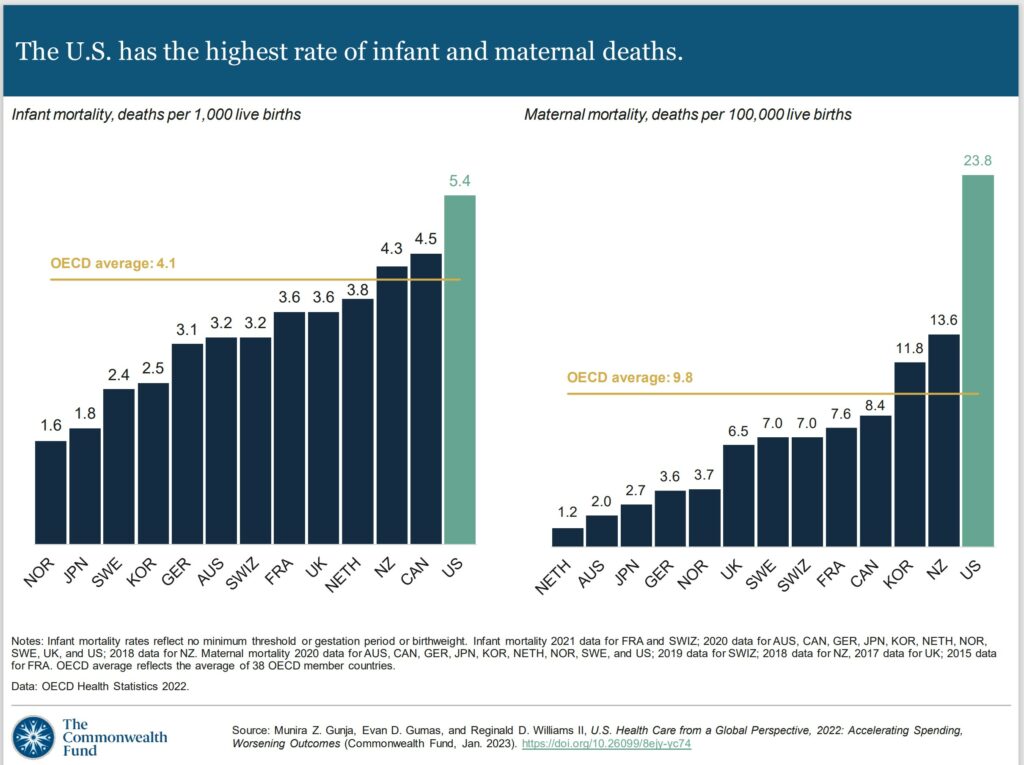

- The U.S. has the lowest life expectancy at birth, the highest death rates for avoidable or treatable conditions, the highest maternal and infant mortality, and among the highest suicide rates.

- The U.S. has the highest rate of people with multiple chronic conditions and an obesity rate nearly twice the OECD average.

- Americans see physicians less often than people in most other countries and have among the lowest rate of practicing physicians and hospital beds per 1,000 population.

- Screening rates for breast and colorectal cancer and vaccination for flu in the U.S. are among the highest, but COVID-19 vaccination trails many nations.

Findings

Health Care Spending and Coverage

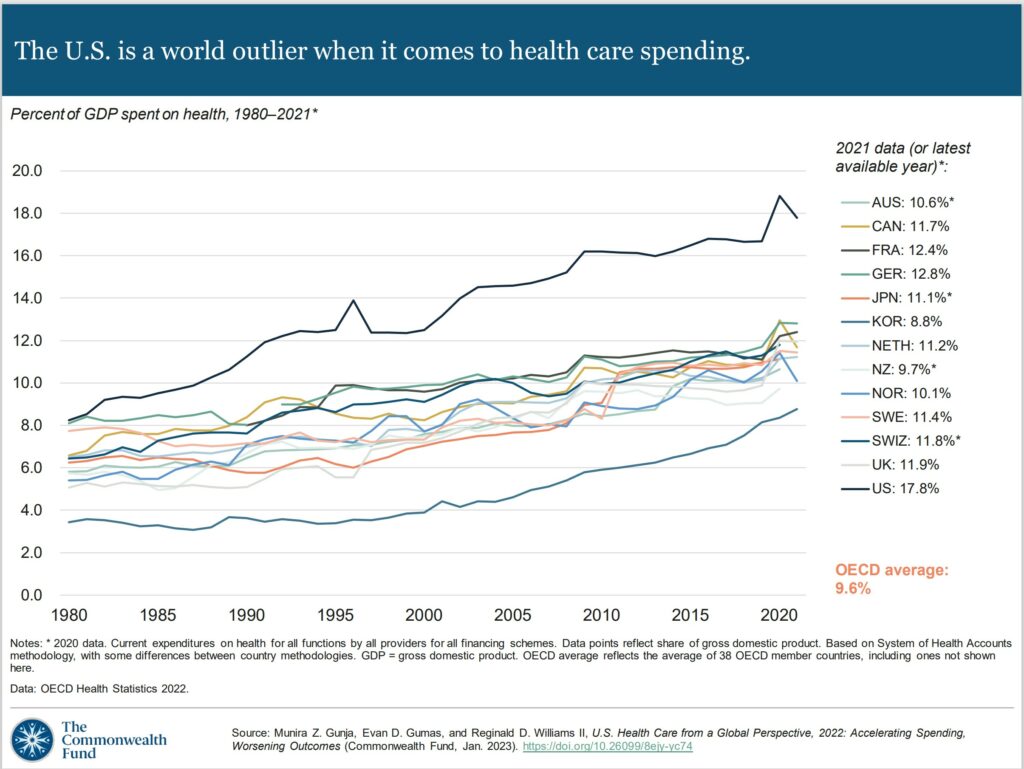

In all countries, health spending as a share of the overall economy has been steadily increasing since the 1980s. Spending growth has outpaced economic growth.4 This growth is in part because of medical technologies, rising prices in the health sector, and higher demand for services.5 In 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic began, health care spending rose rapidly in nearly all countries. Governments sought to mitigate the spread of the disease through COVID testing, vaccine development, relief funds, and other measures.6 Since then, the spending has slowed but still remains higher from years prior.7

In 2021, the U.S. spent 17.8 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) on health care, nearly twice as much as the average OECD country.

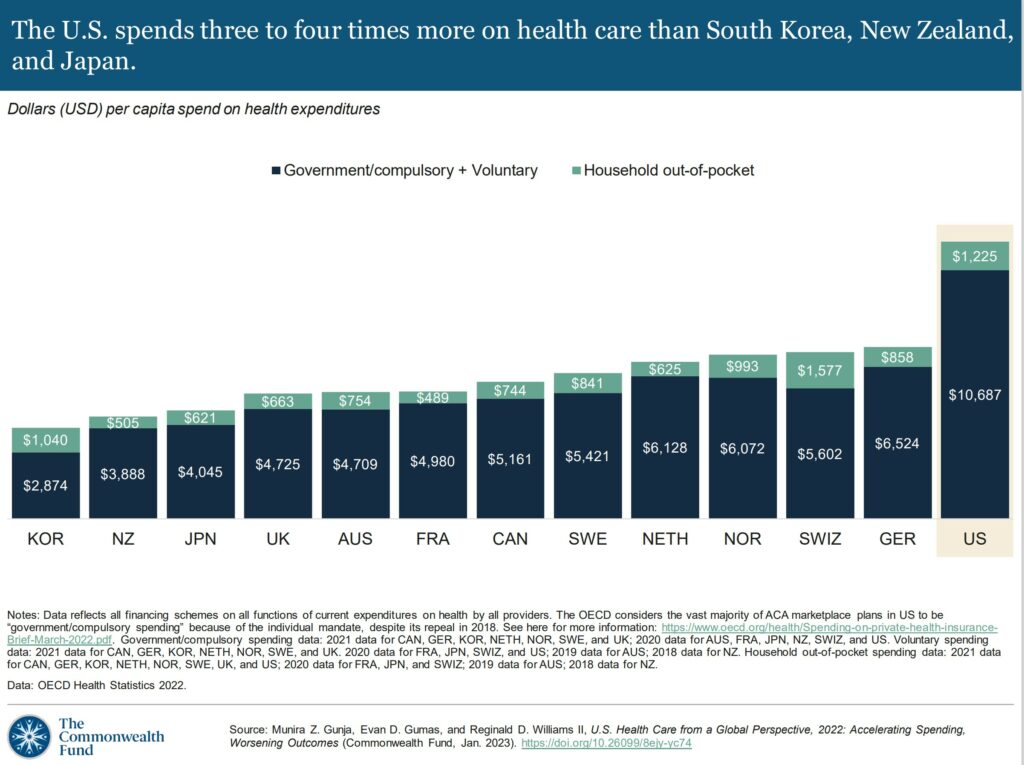

US health spending per person is nearly two times higher than in Germany and four times higher than in South Korea. U.S healthcare expenditures include spending for people in public programs such as Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program, Medicare, and military plans. It also includes spending by those with employer-sponsored coverage, other private insurance coverage, and out-of-pocket healthcare costs.

Except for the U.S, all other countries in this analysis guarantee government, or public health coverage to all of their residents. In addition to public coverage, people in several of the countries have an option to also purchase private coverage. Nearly the entire population In France has both private and public insurance.

In 2021, 8.6 percent of the U.S. population were uninsured.8 The U.S. is the only high-income country where a substantial portion of the population lack any form of health insurance.

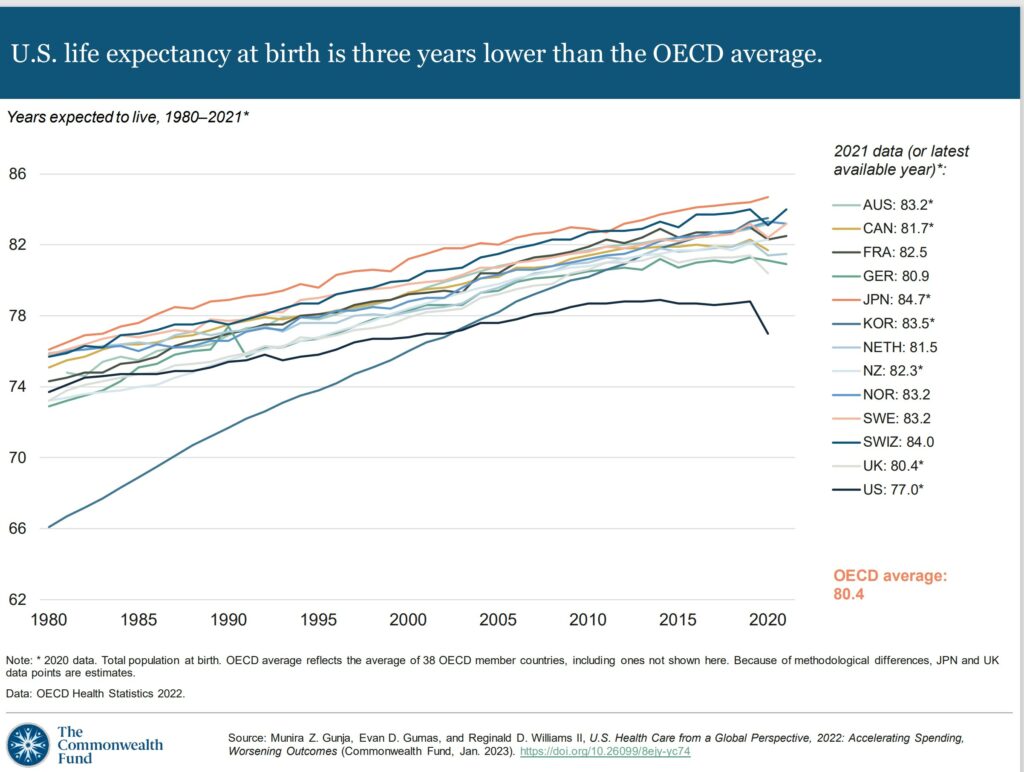

Despite the high U.S. spending, Americans experience worse health outcomes than their peers around world. For example, life expectancy at birth in the U.S. was 77 years in 2020 — three years lower than the OECD average. Provisional data shows life expectancy in the U.S. dropped even further in 2021.9

In the U.S., life expectancy masks racial and ethnic disparities.10 Average life expectancy in 2019 for non-Hispanic Black Americans (74.8 years) and non-Hispanic American Indians or Alaska Natives (71.8 years) is four and seven years lower than it is for non-Hispanic whites (78.8 years).

Meanwhile, life expectancy for Hispanic Americans (81.9 years) is higher than it is for whites and similar to life expectancy in the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Canada. As a group, Asian Americans have a higher life expectancy (85.6 years) than people in Japan.

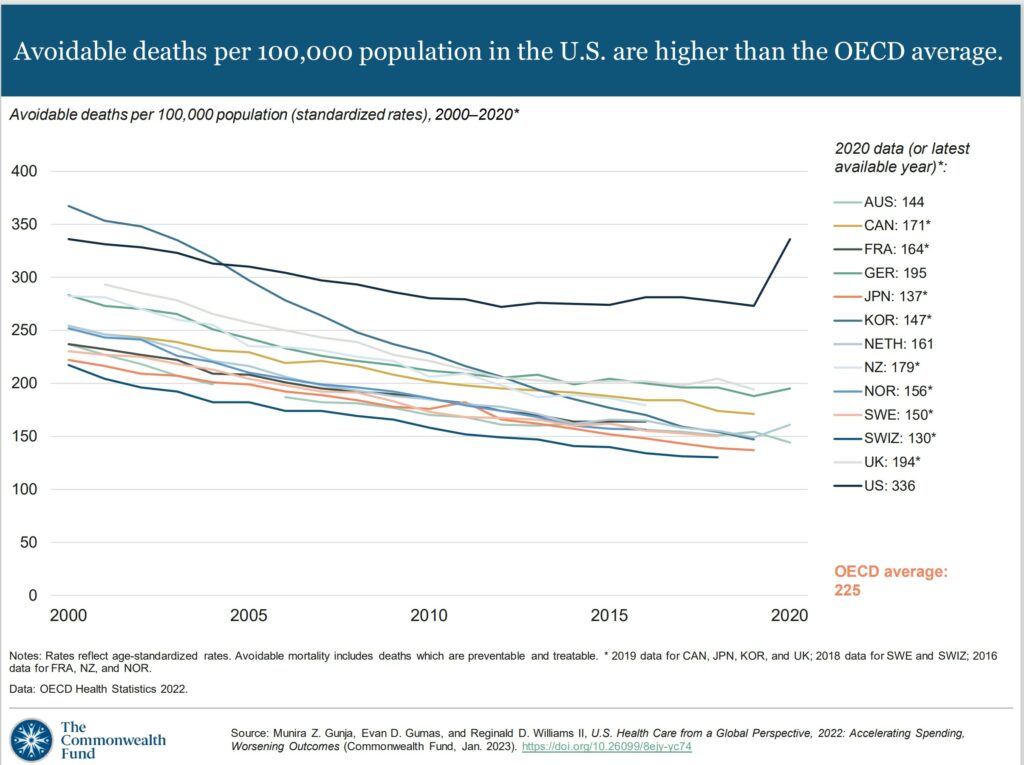

Avoidable mortality refers to preventable deaths which are treatable. Preventable deaths can be avoided through effective public health measures and through primary prevention, such as nutritional diet and exercise. Treatable mortality can be avoided mainly through timely and effective health care interventions, including regular exams, screenings, and treatment.11 Since 2015, avoidable deaths have been on the rise in the U.S., which had the highest rate in 2020 of all the countries in our analysis.

In 2020, the infant mortality rate in the U.S. was 5.4 deaths per 1,000 live births, the highest rate of all the countries in our analysis. In contrast, there were 1.6 deaths per 1,000 live births in Norway.

Women in the U.S. have long had the highest rate of maternal mortality related to complications of pregnancy and childbirth. In 2020, there were nearly 24 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births in the U.S., more than three times the rate in most of the other high-income countries we studied. A high rate of cesarean section, inadequate prenatal care, and socioeconomic inequalities contributing to chronic illnesses like obesity, diabetes, and heart disease may all help explain high U.S. infant and maternal mortality.12

Primary Care Takeover by Commercial Interests, Angry Bear, angry bear blog

U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2022, Commonwealth Fund,

Part Two tomorrow.