This is a story or at least I tried to make it into more like one. The longer version can be found at the Propublica link. I took parts of it linking them together using mostly their wording and blending it with mine. Money and Corporate influence still wins . . . The U.S. Never Banned Asbestos. These Workers Are Paying the Price, ProPublica, Kathleen McGrory and Neil Bedi A few miles up from Niagara Falls was the OxyChem’ facility. The plant’s previous owner was Hooker Chemical. The same company which buried toxic waste in Love Canal,. Then Hooker gave the property over to the city for development in the 1950s. Unlike the horrific tales of the past of Labor working with Asbestos, the current protocols for handling asbestos were so stringent,

Topics:

run75441 considers the following as important: Asbestos, Healthcare, politics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

This is a story or at least I tried to make it into more like one. The longer version can be found at the Propublica link. I took parts of it linking them together using mostly their wording and blending it with mine. Money and Corporate influence still wins . . .

The U.S. Never Banned Asbestos. These Workers Are Paying the Price, ProPublica, Kathleen McGrory and Neil Bedi

A few miles up from Niagara Falls was the OxyChem’ facility. The plant’s previous owner was Hooker Chemical. The same company which buried toxic waste in Love Canal,. Then Hooker gave the property over to the city for development in the 1950s. Unlike the horrific tales of the past of Labor working with Asbestos, the current protocols for handling asbestos were so stringent, workers were facing little threat of exposure at the OxyChem’s Niagara Falls facility. Or so they say.

The Niagara Falls Plant

At the OxyChem’s plant, Henry Saenz worked there for nearly three decades. The reality of working there was far different then the touted protocols as a dozen or so former workers told ProPublica. In the plant asbestos dust hung in the air, collected on the beams and light fixtures, and built up until it was inches thick. Workers were tramping it in and out all day and stirring it up. Often, they were without protective suits or masks. Asbestos was moving around on their coveralls and boots. They implored the plant’s managers to address the conditions, but the dangers remained until the plant closed in late 2021 for unrelated reasons.

It was hard for Henry Saenz to reconcile the science he understood, which he believed OxyChem and government leaders understood too. Reconciliation came hard when measured against what he saw and experienced at the plant every day. He did his best not to inhale the asbestos. After a short time, he came to believe there was no way the killer substance was not already inside of him. The reality of imbibing continuously striking him down in 30. 40, or 50 years later.

Much too late for Henry Saenz, the Environmental Protection Agency was ready to finally outlaw asbestos in a test case with huge implications. If the agency could not ban a substance widely established as harmful as scientists and public health experts argued, it would raise serious doubts about the EPA’s ability to protect the public from any toxic chemicals.

The Companies were poised to meet the challenge.

To fight the proposed ban, the chemical companies turned to a well-worn strategy of marshaling the political heavyweights and the attorneys general of 12 Republican-led states. The company argument were such a ban would create a “heavy and unreasonable burden” on industry.

Lost in this political and legal battle is the story of what happened to the workers in the decades during which the U.S. failed to act. It is not just a tale of workers in a hardscrabble company towns sacrificed to the bottom line of industry. It is also one of federal agencies bending again and again. Federal agencies bending to companies with well-financed lawyers and doing the bidding of company lobbyists of the companies they were to oversee.

It’s the quintessential story of American chemical regulation.

For decades, the EPA and Congress accepted the chlorine companies’ argument of asbestos workers being safe. The regulators left the carcinogen on the list of dangerous chemicals which other countries banned and the U.S. still allows. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration even let OxyChem and Olin into a special program limiting the frequency of inspections at many of the plants.

Along the way, the two companies found they did not need asbestos to make chlorine: They built some modern facilities elsewhere that didn’t use it. Chrysotile asbestos is no longer necessary to produce chlorine today. OxyChem has upgraded some facilities to use polymer membranes instead of asbestos-coated metal screens.

The companies balked at the cost of upgrading the older facilities where it was still in use. Meanwhile they were earning billions of dollars from chemical sales and raked in record profits this year.

Internationally

Globally, governments were taking action to protect their people. Saudi Arabia banned asbestos in 1998, Chile and Argentina did so in 2001, Australia in 2003. By 2005, asbestos was outlawed across the European Union. The head of chemical policy at the European Environmental Bureau Tatiana Santos and a network of environmental citizens’ groups.

“It was a no-brainer,”

EPA Actions

The Environment Protection Agency could have banned asbestos. Congress could also have banned it. But over and over, they gave way in the face of pressure from OxyChem, its peers in the chlorine industry, and state influence.

The EPA tried to enact a ban in the late 1980s, but the companies got ahead of it. Records from the time show corporations testifying the removal of asbestos from chlorine plants would not yield significant health benefits. The workers were only minimally exposed. They also argued it would require “scrapping large amounts of capital equipment” and thus would not be “economically feasible.”

Under federal law at the time, the EPA was obligated to regulate asbestos in the way that was “least burdensome” to industry. That forced the EPA to make a cold calculation: Banning asbestos in chlorine plants would prevent “relatively few cancer cases.” Such action would increase the companies’ costs. So when the agency enacted an asbestos ban in 1989, it carved out an exemption for the mineral’s use in the chlorine industry.

One Failed Attempt

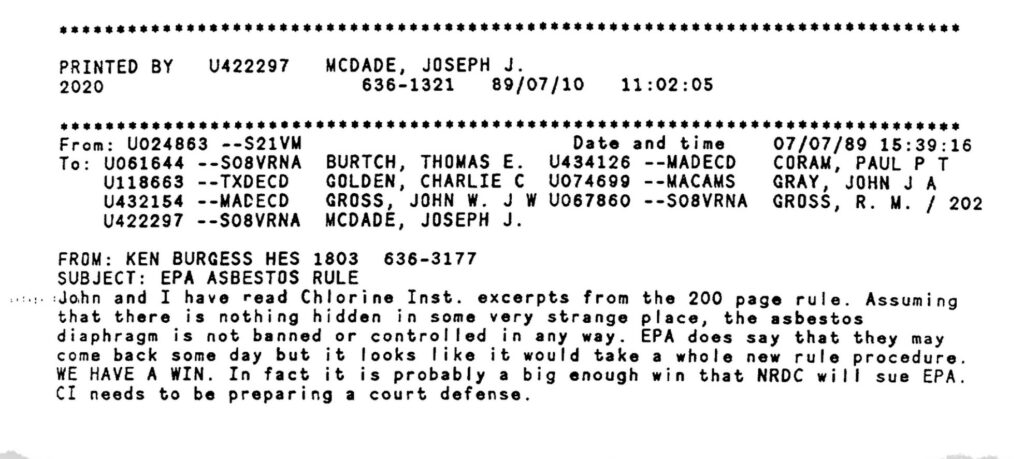

The EPA made it clear that the companies should begin using alternatives to asbestos screens. Company records were made public after litigation and published as part of Columbia University and the City University of New York’s Toxic Docs project. Accordingly, OxyChem already developed screens that didn’t need an asbestos coating. Still, the companies celebrated their immunity from regulation. One Industrial lobbyist declared in an internal communication included in the Toxic Docs project. Subject: EPA Asbestos Rule:

“WE HAVE A WIN,”

One has to wonder what category a “Win” fits into when measured against the numbers of people impacted by poor practices withing the facility and outside of it.

In the end, asbestos was never banned. The asbestos industry challenged the ban in court, and in 1991, a panel of federal judges deemed the rule too onerous and overturned it. The decision was a blow to the EPA. EPA veteran who ran its new-chemicals management branch before he retired in 2020, Greg Schweer . . .

“I still remember the shock on the managers’ faces. The office ‘was full of energized people wanting to make their mark. But things changed after that.’”

The agency shelved efforts to regulate other dangerous substances and wouldn’t attempt a similar chemical ban for 28 years.

Most industries stopped using asbestos anyway, a phenomenon experts largely attribute to a wave of lawsuits from people with asbestos-related diseases. The chlorine industry kept using its asbestos screens. It continued importing hundreds of tons of the substance every year, more than the weight of the Statue of Liberty.

And Congress Fails . . .

In 2002, Sen. Patty Murray a Democrat from Washington, tried to get a ban through Congress. She tried again in 2003 and again in 2007. That year, with Democrats in control of the Senate and House, her effort found some traction.

Occidental Petroleum, OxyChem’s owner, was a force on Capitol Hill, with lobbyists that spent millions influencing policy and a political action committee that pumped hundreds of thousands of dollars into campaigns each election cycle.

The industry had an ally in then-Sen. David Vitter of Louisiana; at the time, at least a quarter of the 16 asbestos-dependent plants in the country were located in the Republican senator’s home state, records show. At a hearing in June 2007, Vitter echoed the chlorine industry’s standby talking point, that its manufacturing process involved “minimal to no release of asbestos and absolutely no worker exposure.”

“Now, if this were harming people or potentially killing people, that would be the end of the argument, we should outlaw it. But there is no known case of asbestos-related disease from the chlor-alkali industry using this technology.”

A California Democrat in favor of the ban, Sen. Barbara Boxer pushed back saying the chlorine manufacturing process was “not as clean as one would think.” But to build support for the bill, proponents ultimately agreed to exclude products that might contain trace levels of asbestos, such as crushed stone, as well as the asbestos used in the chlorine industry.

The bill passed out of the Senate on a unanimous vote. Many of the public health advocates championing the initial measure were opposing the watered-down version. They were claiming it was not enough and it failed to find support in the House. Vitter, who later went on to lobby for the American Chemistry Council, did not respond to requests for an interview.

In the 15 years that followed, congressional attempts to ban asbestos would continue to fall short.