By Steve Roth Originally posted at Wealth Economics Please excuse two paragraphs of a personal insight up front here. I think it’s pertinent. What follows are some serious research results, just out, that I think are hugely revealing about the ways of the (economic) world. I had a visit from an old and good friend recently: dad of one of my kids’ best childhood friends, and in more recent years a business/investing colleague. We both had very prosperous upbringings, way beyond anything you’d call just “economically secure.” And while both of us worked hard (sometimes very hard) in our lives, made good decisions, and generally lived within our means, our lives were easy, and very pleasant. My friend and I have also been very successful. He

Topics:

Steve Roth considers the following as important: Nobel Laureates, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Joel Eissenberg writes Time for Senate Dems to stand up against Trump/Musk

by Steve Roth

Originally posted at Wealth Economics

Please excuse two paragraphs of a personal insight up front here. I think it’s pertinent. What follows are some serious research results, just out, that I think are hugely revealing about the ways of the (economic) world.

I had a visit from an old and good friend recently: dad of one of my kids’ best childhood friends, and in more recent years a business/investing colleague. We both had very prosperous upbringings, way beyond anything you’d call just “economically secure.” And while both of us worked hard (sometimes very hard) in our lives, made good decisions, and generally lived within our means, our lives were easy, and very pleasant.

My friend and I have also been very successful. He tends to attribute that more to his hard work and good decisions, while I’m more likely to just thank my lucky stars. I’ve got a pretty odd and quirky mind by most people’s standards, and I spend an inordinate amount of my time inside that mental maze (or dumpster fire, if you prefer). So when I see a troubled person wandering around downtown Seattle with their subconscious leaking all over the poor tourists, I’m like, “There but for the grace of god go I.” That could so easily have been me, if I’d suffered the slings and arrows that so many in this world endure, if I’d had to bear those fardels.

Which all brings me to a remarkably good new open-access (!) study, of Nobel Laureates over the past 125 years (Novosad, Asher, Farquharson, & Iljazi). It covers science prizes only, but includes economists (yeah I know). You can get the big takeaways with details, tables, and graphs, from Paul Novosad’s excellent and meaty twitter thread @paulnovosad. But I want to highlight one big up-front finding, with some commentary.

A main question from this team: how many woulda, shoulda, coulda-been laureates have spent their lives doing menial or low-level administrative jobs, etc? (Related question: how many people ~just like me are out there who didn’t have my easy life, and should have had my level of success but…didn’t?) The team can’t and doesn’t try to answer that, but their study of the successes (compared to the total population) gives some strong suggestions at least.

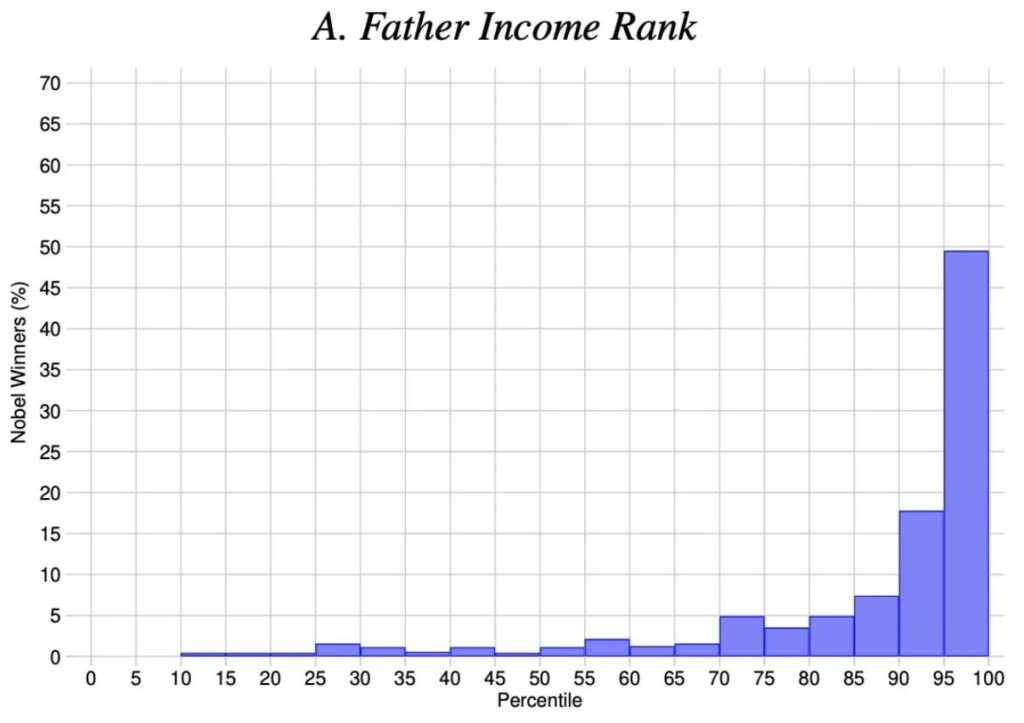

Novosad highlights the biggest issue right up front: ~65% of laureates had fathers in the top -10% income class.1 The other 90% get the 35% leavings.

Likewise, there are big correlations with fathers’ education levels, occupations (lots of business owners!), etc. People tend to explain these facts away in various ways, mostly of the “they have good genes so they deserve it and it makes us all better off” variety. Let’s take a look at those.

The just-desserts explanation. “People are successful because they’re smart.” (Or diligent, patient, choose your self-congratulatory Puritan virtue.) Lurking just below the surface of that: “so they deserve their success.” The silent, unstated, but inevitable obverse of that: if people don’t have what it takes to build and live a comfortable and secure life despite all the “opportunity” in this economy, that’s also just desserts.

When I hear people going on about “providing opportunity” (yes Kamala, I’m talking to you), I immediately want to point out that the overwhelmingly dominant, #1 determinant of “opportunity” is…having some money. More is better. Many/most people who grow up with family money and support, either moderate or massive, don’t seem to realize this. It’s always seemed glaringly obvious to me, with me as a prime example.

No, of course money isn’t the only determinant. Please don’t waste our time writing that comment. I’m saying that having some money is a necessary versus sufficient condition for life success. Imagine if we were all born with nothing.2

The economic efficiency argument. This, again silently and I think mostly unthinkingly, is based on the “just desserts” assumption. “Successful people have abilities and character that make them successful, and we need to ‘incentivize’ those people to work hard by giving them lots of money. That makes us all better off.” But if a comfortably well-off, prosperous, or especially wealthy family is the dominant (say 75%) reason for people’s success (or even, say, 30 or 40%?), that argument pretty much falls apart.

If we want widespread and inclusive economic prosperity, success, and opportunity, we need to give everyone a solid, secure, and comfortable economic platform and springboard for success, without trying to determine whether they “deserve” it. (There’s no way to know in advance whether they will deserve it, by whatever measure you might choose to define success or just desserts…)

Wealth is insanely concentrated into ever-fewer hands: individuals, families, and multigenerational dynasties. 55%–65% of that wealth is not earned, but inherited — no “just desserts” in sight, just the lucky-sperm contest. If only that narrow, wealthy group is able to produce Nobel-level discoveries and accomplishments, we are all “impoverished.” And many millions, over many decades, are downright impoverished. Likewise, their children. World without end, amen.

1 The researchers painstakingly assembled the fathers’ histories from historical documents. Unfortunately, I’m sure information on fathers’ wealth (as opposed to income) was largely unavailable, and they don’t report it.

2 Cue the irresistible one-liner: “All people are created equal. They just don’t stay that way very long.” Or in my words: “You start receiving the benefits of your inheritance approximately nine months before you’re born, and continue to receive it throughout your life. Any final bequest is just a cherry on top.”