By Eric Tymoigne

On one side, critics argued that MMTers say nothing new when MMTers emphasize US government’s monetary sovereignty; “everybody knows this” is a common refrain. On the other side, critics argue that MMT incorrectly merges the US Treasury and Fed into a US government, which ignores the fact that the US Treasury can run out of money because it needs to tax and issue bonds first before it can spend.

Something is amiss. This post shows that MMT can be understood from two viewpoints. One is the consolidation viewpoint and another is the coordination viewpoint. Both lead to the same conclusion; money is never an issue. US government can’t run out of money, US Treasury can’t run out of money. They are other implications in terms of public finances (the role of taxes, the role

Articles by Eric Tymoigne

“What You Need To Know About The $22 Trillion National Debt”: The Alternative SHORT Interview

February 17, 2019Steven Rattner’s opinion piece in the New York Times and Furman’s interview on National Public Radio are perfect examples of the ideas that MMT want to debunk. Deficits are not normal; deficits crowd out private investment; the public debt is a burden on our grandchildren; our ability to respond to societal problems is limited by the fact that the US government does not have enough money to confront them.

Below is an alternative interview to the Furman’s interview that reviews these points. This is the short version that provides quick-bit answers. A long version that provide data and more elaborated answers is available also on this blog (Dear Ms. Cornish, I hope you will forgive me but I will plagiarize you entirely for the sake of this exercise).

AUDIE CORNISH, HOST:

The national

“What You Need To Know About The $22 Trillion National Debt”: The Alternative Interview

February 16, 2019Steven Rattner’s opinion piece in the New York Times and Furman’s interview on National Public Radio are perfect examples of the ideas that MMT want to debunk. Deficits are not normal; deficits crowd out private investment; the public debt is a burden on our grandchildren; our ability to respond to societal problems is limited by the fact that the US government does not have enough money to confront them.

Below is an alternative interview to the Furman’s interview that reviews these points. This blog will run like a traditional interview and all the evidence for the points made are in appendices at the end (Dear Ms. Cornish, I hope you will forgive me but I will plagiarize you entirely for the sake of this exercise).

AUDIE CORNISH, HOST:

The national debt surpassed $22 trillion this

Money and Banking Post 21: The Interest Rate

October 12, 2017By Eric Tymoigne

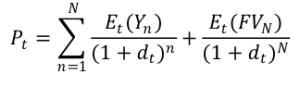

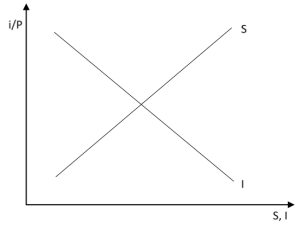

In Post 20, a lot is said about the role that the rate of return on financial instruments—the interest rate—plays on the pricing on securities, but little was said about what determines that rate of return. Two competing theoretical frameworks explain what influences the interest rate, one of them emphasizes the role of real factors and the other emphasizes monetary factors.

Real Theory of Interest Rate: Natural Interest Rate and Expected Inflation

Gross Substitution and Indifference Condition: Determinant of the Nominal Interest Rate

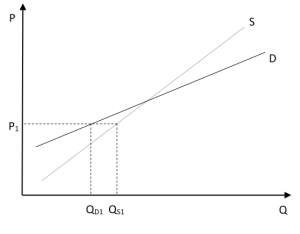

The real exchange framework (Post 12) emphasizes the role played by real variables in the decision-making process of any rational economic unit. People are not fooled by mere improvement in monetary income because they only care about

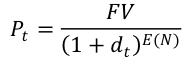

Money and Banking Post 20: Pricing Securities

August 30, 2017A Small Detour: Savings Account and Interest Compounding

A typical way to think about interest rates is to study how a savings account works. Suppose Mr. X puts $1000 in a savings account that provides a one percent annual interest rate. In that case, X will get at the end of:

Year 1: $1010 = $1000(1 + 0.01)

Year 2: $1020.1 = $1010(1 + 0.01) = $1000(1.01)2

…

Year 5: $1051.01 = $1000(1.01)5

Several things are worth noticing:

The rate of return is fixed by the issuer of the account (1%)

Principal rises over time: The longer X keeps the funds in his saving account, the greater, the total amount of principal due by a bank when X chooses to withdraw all its funds.

Income rises over time: Interest income earned is automatically added to the outstanding amount of funds ($1000, $1010, etc.)

Money and Banking – Part 19 (A): Financial institutions: An overview

August 6, 2017Part A | Part B | Part C

Erratum on Post 18: Figure 18.10 has reversed proportions: about 30 percent are issued by nonfinancial corporations.

Note: As I was afraid it would happen, someone emailed me to take issue with the way I use the term promissory note. “Promissory note” has a specific meaning in the law—it is a specific type of financial instruments—but Post 18 uses the term conceptually to mean any formal promise made by someone—a synonymous to financial instrument—, which may create some confusion. I am trying to find an alternative terms that contains the word “promise” (maybe promissory paper?, promissory contract? Contractual promise?) any suggestion welcome. For the moment, I will use the terms financial instrument, or promise…maybe that is good enough…

Financial

Read More »Money and Banking – Part 19 (B): Financial institutions: An overview

August 6, 2017Part A | Part B | Part C

Regulated Portfolio Management Companies: Mutual Funds and Others

Portfolio management companies provide a wide variety of placement opportunities to economic units with spare funds who do not want to, or cannot, directly buy securities or other assets. There are three broad types of portfolio management companies: mutual funds, closed-end funds, and unit investment trusts (UITs). One of the main differences between them is the characteristics of the shares they issue in terms of marketability and redeemability. Mutual fund shares are nonmarketable and redeemable on demand, closed-end fund shares are marketable and irredeemable, and UIT shares are marketable and redeemable on demand. Closed-end funds and UITs do not continuously offer their shares for sale.

Money and Banking – Part 19 (C): Financial institutions: An overview

August 6, 2017Part A | Part B | Part C

Farmer Mac, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Sallie Mae

This section closes the presentation of government-sponsored enterprise with a quick look at other GSEs. They work in a similar fashion to the FCS, by issuing securities and using the proceeds to buy or to back illiquid financial instruments held by financial institutions. The goal is once again to lower the level and volatility of interest rates on specific financial instruments and to encourage credit for specific economic activities.

A GSE that is formally part of the FCS but independent from it is the Federal Agricultural Mortgage Corporation (Farmer Mac). Farmer Mac issues its own securities and use the proceeds to purchase mortgages from financial institutions that help fulfill the mission of the

Money and Banking—Part 18 (B): Overview of the Financial System: A World of Promises

May 30, 2017Due to the size of this post, it has been split into 2. You can find part A here.

Monetary instruments

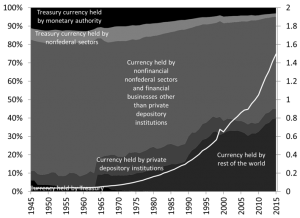

Monetary instruments are the last type of marketable promissory notes. Post 15 and Post 16 are devoted to their analysis. One of the main characteristics of monetary instruments is that their term to maturity is instantaneous, that is, they can be returned to the issuer at the will of the bearer. In terms of cash, that is physical monetary instruments, the Financial Accounts of the United States make a difference between currency, Treasury currency, and coins. Coins are not included in the Accounts, currency refers to cash issued by the Federal Reserve (Federal Reserve notes), and Treasury currency refers to cash issued by the US Treasury (the Treasury no longer issues any currency

Money and Banking—Part 18 (A): Overview of the Financial System: A World of Promises

May 30, 2017Due to the size of this post, it was split in two. You can find Part B here.

The M&B series is back! The goal is to finish the first complete draft of the book by the time I need to teach my Money and Banking course. Over the coming months, the following topics will be covered.

Overview of the financial system

Federal Reserve System institutional analysis

Interest rate and interest rate structure

Pricing of securities

Off balance sheet: Securitization

Off balance sheet: Derivatives

Monetary policy in action (issues surrounding interest-rate rules, transmission channels, etc.)

International monetary arrangements and exchange rates

Modeling (theory of the circuit, including the money supply in models, stock-flow coherency, portfolio constraints, capital gains, using models, etc.)

With

Bill Clinton’s Surplus: Not Something to Celebrate

December 20, 2016Video from Eric Tymoigne’s Modern Money students at Lewis and Clark College.[embedded content]

Share this:

Money and Banking Part 17: History of Monetary Systems

June 4, 2016By Eric Tymoigne

This is the last post of this series. Many more topics need to be covered to make a full Money and Banking course, but the series should help those of us who are dissatisfied with the current Money & Banking textbooks (I don’t use any).

Here is what is coming up in the near future: I will edit all the posts for typos (most of them hopefully) and to account for comments I received. Devin Smith kindly agreed to post the changes without changing any of the links. Formatting the text from a Word doc to a webpage is actually tedious work so many thanks to Devin. An M&B menu will be created at the top of the NEP homepage that will direct readers to links for each post. I will also make a fancy-looking pdf with all the posts, a table of content, etc. It will be more textbook-like and may be more appealing for some readers.

In the long term, there is a textbook coming. When? Difficult to say. I plan to write most of the first draft of the text next spring while on sabbatical. Then, several rounds of testing (and rewriting) must be done to include feedbacks from students. A test bank and exercises must be created and tested too. So there is some work to do.

Money and Banking Part 16: FAQs about Monetary Systems

May 28, 2016By Eric Tymoigne

The following answers a few question in order to illustrate the previous post and to develop certain points.

Q1: Can a commodity be a monetary instrument? Or, does money grow on trees?

Let us tackle the idea that “gold is money”. Clearly, a gold ingot is not a monetary instrument. There is no issuer, no denomination, no term to maturity or any other financial characteristics. A gold ingot is just a commodity, a real asset not a financial asset. On the other hand, gold coins have been monetary instruments and are still issued at times (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Gold (ingots) vs. Gold Coin (2009 $50 American Buffalo Gold Coin)

Similarly, it is incorrect to state that “salt was money” because salt is a commodity that embeds no promise; however, Marco Polo noted that in the Chinese province of Kain-du:

There are salt springs, from which they manufacture salt by boiling it in small pans. When the water is boiled for an hour, it becomes a kind of paste, which is formed into cakes of the value of two pence each. […] On this latter species of money the stamp of the grand khan is impressed, and it cannot be prepared by any other than his own officers. Eighty of the cakes are made to pass for a saggio of gold.

Money and Banking Part 15: Monetary Systems

May 20, 2016By Eric Tymoigne

Throughout this series, posts have used balance sheets extensively to get an understanding of the monetary operations of developed economies, but nothing has been said about what a monetary instrument is. It is time to spend some time on the nature of monetary instruments and the inner workings of monetary systems. A monetary system is composed of two core elements:

A unit of account that provides a common method of measurement: the euro (€), the pound sterling (₤), the yen (¥), the dollar ($), etc.

Monetary instruments: specific financial instruments denominated in the unit of account and issued by the government and the private sector.

This post first explains what financial instruments are and how monetary instruments fit within the existing range of instruments. It then delves into what determines the nominal and real value of monetary instruments and into what makes them accepted.

Financial Instruments

Balance sheets contain many types of financial instruments. Some of them are issued by an economic unit (financial liabilities), others are held by that same economic unit (financial assets). Financial instruments are just formal promises to make monetary payments.

Money and Banking Part 14: Financial Crises

May 11, 2016By Eric Tymoigne

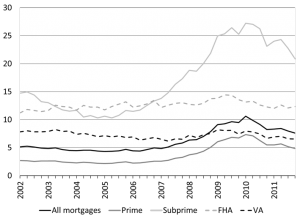

While visiting the London School of Economics at the end of 2008, the Queen of England wondered “why did nobody notice it?” In doing so, she echoed a narrative that had been promoted among some prominent economists: the Great Recession (“it”) was an accident, a random extreme event and no one so it coming. This narrative is false. Quite of few economists saw it coming and it was not an accident. A previous post showed how different theoretical framework about financial crises lead to different regulatory responses. This post studies more carefully the mechanics of financial crises and how an economy gets there.

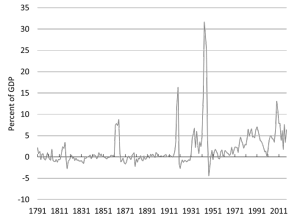

Debt Deflation

Definitions of financial crises can be more or less broad. Some economists restrict the definition to banking crises, others may use a statistical definition that takes a specific percentage fall in a financial index. In any case, financial instability has increased since the 1980s.

The most serious financial crises involve reinforcing feedbacks between asset prices and leverage, leading to a downward spiral of debt write offs and fall in asset prices. These financial crises are called “debt deflations” after Irving Fisher’s analysis of the Great Depression.

Money and Banking Part 13: Balance Sheet Interrelations and the Macroeconomy

April 23, 2016By Eric Tymoigne

Past posts have focused on the mechanics of a specific balance sheet, specifically that of the central bank and of private banks. This post looks at the balance-sheet interrelations between the three main macroeconomic sectors of the economy: the domestic private sector, the government sector and the foreign sector. This macro view provides some important insights about issues such as the public debt and deficit, policy goals that are more likely to be achieved, the business cycle, among others.

A primer on consolidation

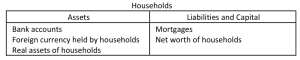

The balance sheet of the domestic private sector puts together the balance sheets of all domestic private economic units, households, financial businesses, non-financial businesses. This means that claims that these sectors have on each other are removed from the balance sheet of the domestic private sector. For example, assume that the following two balance sheets exist

If they are consolidated we have as a first step:

The terms in red appear on both sides of the balance sheet and are eliminated in the consolidation process so the balance sheet of households and banks is:

The only financial claims left are those that are issued to, and issued by, other sectors of the economy than households and banks. Thus, the consolidation process eliminates some important financial interlinkages.

Read More »Money and Banking Part 12: Economic Growth and the Financial System

April 14, 2016By Eric Tymoigne

Money is the blood of capitalist enterprise and finance is about money now for money later. As such a well-developed financial system is essential for economic activity in a capitalist economy. The broader the range of promissory notes that can be issued, the more accommodative the financial system is to the demands of the productive system. Households cannot fund the purchase of a house with a credit card and there is no point in buying groceries with a 30-year mortgage. While all this may seem obvious, economists have been divided about the relevance of finance for economic activity. This divide ultimately rests on different premises on how to do economics, which John Maynard Keynes characterized as Real Exchange Economy versus Monetary Production Economy.

Before I go further, a word of caution. Economists (and national income accounts) use the word “investment” in a specific way. Investment means adding to the amount of real assets, i.e. growing productive capacities. One cannot invest in stock, bonds, and other financial assets but merely in machines and raw material. Portfolio choice, which is usually what people have in mind when talking about (financial) investment, is not the same thing as (physical) investment.

The Real Exchange Economy (REE)

Money supply is a veil

Until the 1980s, most economists believed that finance is neutral, i.e.

Money and Banking – Part 11: Inflation

April 5, 2016By Eric Tymoigne

We are done with the study of banking operations. The next step is to incorporate them into the analysis of macroeconomic issues and this post begins on such topic by focusing on inflation. When inflation is mentioned, it is usually in relation to the cost of buying newly produced goods and services for consumption purpose. Another type of inflation concerns asset-prices, i.e. the price of non-producible commodities and old producible commodities. This post does not study assets-price inflation, which concerns theories of interest rate.

Theories of Output PricesThere are two broad ways to categorize existing explanations of inflation (and deflation); monetary explanations and real explanations (“real” means related to production). Below are two popular theories based on such categorization.

The Quantity Theory of Money (QTM): Monetary View of Inflation

The QTM starts with the identity MV ≡ PQ with M the money supply, V the velocity of money (the speed at which money supply circulates to complete all required transactions), P the price level, and Q the quantity of output. The identity is a tautology, it just says that the amount of transactions on goods and services (PQ) is equal the amount of financial transactions needed to complete those transactions.

Money and Banking-Part 10: Monetary Creation by Banks

March 27, 2016By Eric Tymoigne

The last three posts have explained how the operations of banks are constrained by profitability and regulatory concerns, and how banks operate to bypass these constraints. It is now time to go into the details of how banks get involved into providing credit and payment services to the rest of the economy.

Monetary Creation by Banks: Credit and Payment Services

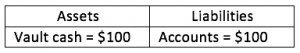

Bank A just opened for business and its balance sheet looks like this:

Now come household #1 who wants to buy a house worth $100 from household #2. #1 sits down with a banker (a.k.a. loan officer) who asks a few questions regarding annual income, available assets, savings, the downpayment #1 is willing to make, among others. The banker asks for documentations that corroborate the answers provided by #1.

The banker shows to the #1 what financing options are available, that is the banker shows to #1 what type of mortgage note household #1 has to issue to be accepted by bank A. Figure 1 is taken from an actual bank website.

For 100% financing (no downpayment by household), the bank is prepared to provide up to $330,000 and it will only accept a 30-year 5.125% fixed-rate mortgage note. The bank will not accept a 20-year mortgage note, or a 3.875% note for 100% financing.

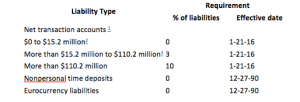

Money and Banking – Part 9: Banking regulation

March 21, 2016By Eric Tymoigne

It may surprise you to know that the banking sector is one of the most regulated industries in the United States with a bank having to file regulatory documents with several agencies. These regulations determine how banks should and should not operate their business in terms of many aspects; from disclosure of information to potential customers, to means of determining creditworthiness of a potential client, to the amount of reserves to hold, to management issues, among others. For example the National Association of Mortgage Brokers noted in 2006

Mortgage brokers are governed by a host of federal laws and regulations. For example, mortgage brokers must comply with: the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA), the Truth in Lending Act (TILA), the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA), the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), and the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTC Act), as well as fair lending and fair housing laws. Many of these statutes, coupled with their implementing regulations, provide substantive protection to borrowers who seek mortgage financing. These laws impose disclosure requirements on brokers, define high-cost loans, and contain anti-discrimination provisions.

Money and Banking-Part 8: The Private Banking Business

March 12, 2016By Eric Tymoigne

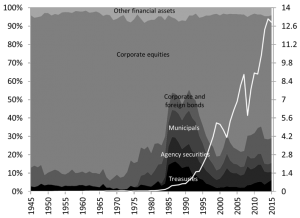

The US financial system is extremely complicated and this series shades light only on some corners of that system by focusing on the banking sector. Here is a broad picture of the US financial system (some things have changed since the time I made this). Since the beginning of this M&B series, posts have emphasized the importance of balance sheet to get a solid understanding the mechanics at play in the financial sector. This post continues that trend.

The balance sheet of a bank

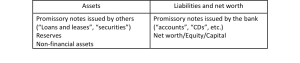

The balance sheet of a private commercial bank looks like this:

Promissory notes issued by others include any kind of agreement between the bank and an entity that made a promise to pay a monetary amount. That entity can be a domestic or foreign, household (mortgage note or any other customer notes), company (business credit, corporate securities), or government (treasuries, municipals). Promissory notes may or may not have a market in which they can be traded. If they have a market they are called “securities”, if they don’t they are called “loans and leases” (I explained in a previous post, and will do it again in the next post, the word “loan” is really inappropriate). A previous post studied in details reserves, which are themselves a promissory note as we will see later, but are singled out for analytical purpose.

Read More »Money and Banking Part 7

March 6, 2016By Eric Tymoigne

Given that the concept of leverage will be used often in the upcoming posts, this post spends some time explaining what leverage is and some of its impacts on the balance sheet of any economic unit.

What is Leverage?

Leverage is the ability to acquire assets in an amount that is larger than what one’s own capital allows to buy. Say that an economic unit has a net worth of $100, that it has no debt and that the counterparty is $100 in cash. The balance sheet looks like this:

Figure 1. A balance sheet without leverage

What is the leverage? Leverage = asset/net worth = asset/equity = A/E = $100/$100 = 1: No debt used, all the cash the economic unit has was acquired without the help of any debt (e.g., grandpa gave $100 for Christmas, or you worked to get $100). Now the economic unit decides to use its cash to buy a bond that pays 10% yearly.

Figure 2. Another balance sheet without leverage

What is the leverage? Leverage = A/E = $100/$100 = 1: still no leverage but this balance sheet allows the economic unit earns interest income: Cash inflow = $10 yearly as interest payment.

Money and Banking – Part 6

February 14, 2016Treasury and Central Bank Interactions

This post concludes our study of central banking matters (there would be a lot more to cover…maybe another time). The post studies how the Fed is involved in fiscal operations and how the U.S. Treasury is involved in monetary-policy operations. The extensive interaction between these two branches of the U.S. government is necessary for fiscal and monetary policies to work properly.

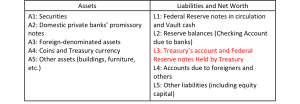

Once again the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve provides a simple starting point. The Treasury holds an account (called Treasury’ General Account, TGA) at the Fed, which is part of L3.

Monetary Policy and the U.S. Treasury

When Treasury spends, it debits funds from its TGA and credits the account of private economic units. Simultaneously reserve balances are credited. Say the Treasury buys $100 worth of paper from a paper company

If Treasury receives $25 of income tax payments, the following happens:

Therefore, in case of a deficit (taxes less than expenses), there is a net injection of reserves. The consolidation of the two previous fiscal operations is:

If the Fed does not neutralize the impact of the fiscal deficit by removing the extra reserves, banks will dump everything in the Fed Funds market and the FFR will rapidly falls toward 0%.

Read More »Money and Banking Blog – Part 4

January 30, 2016By Eric Tymoigne

For convenience, I have put the balance sheet of the Fed below. A previous post examined the balance sheet and another one provided important information about the meaning of reserves and other basic concepts and their relation to the balance sheet of the Fed. Now let’s look at monetary-policy implementation.

What does the Fed do in terms of monetary policy and why?

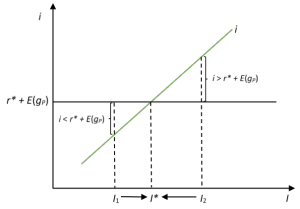

While details in operating procedures have changed through time, the Federal Funds rate (FFR) has progressively gained in importance as a relevant operating tool (i.e. means to implement monetary policy) since the 1920s. The FFR is the rate at which participants in the Fed Funds market lend and borrow Fed Funds to each other for one day (overnight).

Fed Funds are the dollar value of the Fed accounts (L2, L3, L4). Holders of these accounts include private banks, Treasury, GSEs, IMF, securities firms, among others. Some of these account holders need more funds (usually banks) while others usually have more than needed. The Fed Funds market allows these participants to meet and make deals.

The Fed is highly interested in the FFR and aims at targeting that rate, i.e. the Fed wants to make sure that the FFR (that is market determined) does not deviate too much from the FFR desired by the Fed (the FFR Target) (Figure 1).

Money and Banking – Part 3

January 24, 2016By Eric Tymoigne

(A quick note: I noticed that the M&B posts get posted on other blogs. If you want me to respond to you, you should comment at NEP.)

MONETARY BASE AND THE BALANCE SHEET OF THE FED.

The previous post examined the balance sheet of the central bank:

Now that we have an understanding of how the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve works, it is possible to go into the details of how the Fed operates in the economy in terms of monetary policy.

To understand what the Fed does, we first need to define the monetary base and see how it relates to the Fed’s balance sheet. We will quickly look at the difference between monetary base and money supply, and we will also look more carefully at what reserves are.

The Monetary Base and the Money Supply

The monetary base (aka “High-Powered Money”) is defined as:

Monetary Base = Reserve balances + vault cash + cash in circulation

In its widest meaning “in circulation” means any Federal Reserve Notes (FRNs) outside the Federal Reserve banks and any Treasury-issued cash outside Treasury. Economists prefer to use a narrower definition and we will use it here. Cash in circulation is any currency outside Treasury, Fed, and private banks (“vault cash”)—what is held by “the public.”

Technically, cash means currency and coins. The Fed and Treasury use the word “currency” to mean paper money only.