By Eric Tymoigne While visiting the London School of Economics at the end of 2008, the Queen of England wondered “why did nobody notice it?” In doing so, she echoed a narrative that had been promoted among some prominent economists: the Great Recession (“it”) was an accident, a random extreme event and no one so it coming. This narrative is false. Quite of few economists saw it coming and it was not an accident. A previous post showed how different theoretical framework about financial crises lead to different regulatory responses. This post studies more carefully the mechanics of financial crises and how an economy gets there. Debt Deflation Definitions of financial crises can be more or less broad. Some economists restrict the definition to banking crises, others may use a statistical definition that takes a specific percentage fall in a financial index. In any case, financial instability has increased since the 1980s. The most serious financial crises involve reinforcing feedbacks between asset prices and leverage, leading to a downward spiral of debt write offs and fall in asset prices. These financial crises are called “debt deflations” after Irving Fisher’s analysis of the Great Depression.

Topics:

Eric Tymoigne considers the following as important: Eric Tymoigne, money and banking

This could be interesting, too:

Mike Norman writes Banks And Money (Sigh) — Brian Romanchuk

Mike Norman writes Lars P. Syll — The weird absence of money and finance in economic theory

Eric Tymoigne writes Can the US Treasury run out of money when the US government can’t?

Eric Tymoigne writes “What You Need To Know About The Trillion National Debt”: The Alternative SHORT Interview

By Eric Tymoigne

While visiting the London School of Economics at the end of 2008, the Queen of England wondered “why did nobody notice it?” In doing so, she echoed a narrative that had been promoted among some prominent economists: the Great Recession (“it”) was an accident, a random extreme event and no one so it coming. This narrative is false. Quite of few economists saw it coming and it was not an accident. A previous post showed how different theoretical framework about financial crises lead to different regulatory responses. This post studies more carefully the mechanics of financial crises and how an economy gets there.

Debt Deflation

Definitions of financial crises can be more or less broad. Some economists restrict the definition to banking crises, others may use a statistical definition that takes a specific percentage fall in a financial index. In any case, financial instability has increased since the 1980s.

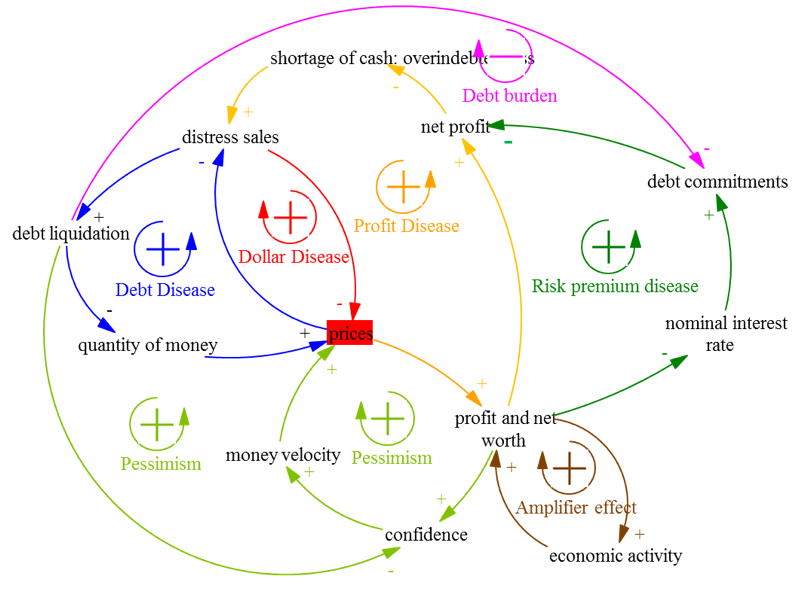

The most serious financial crises involve reinforcing feedbacks between asset prices and leverage, leading to a downward spiral of debt write offs and fall in asset prices. These financial crises are called “debt deflations” after Irving Fisher’s analysis of the Great Depression. The main implication of a debt deflation is that market mechanisms breakdown under the combination of over-indebtedness and deflation: lower prices do not clear markets but make matter worse.

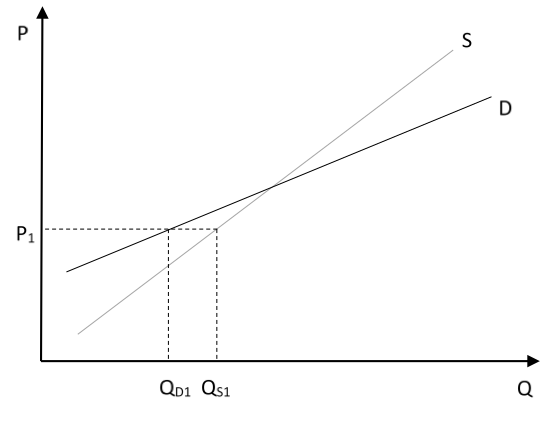

One way to represent that graphically is with the following supply and demand diagram. The demand curve is upward slopping because higher prices lead to higher wealth and so higher demand for goods and services. There is an equilibrium point but it is an unstable equilibrium, i.e. price mechanisms do not bring the market to equilibrium. For example, at P1 there is a surplus of goods and services, this leads to a fall in prices. The deflation decreases the quantity supplied but also quantity demanded in such a way that the surplus grows. A similar result can be found by postulating a downward slopping supply curve. As prices fall, more goods and services are supplied to try to service debts.

Figure 1. An unstable equilibrium

There are many feedback loops involved in a debt deflation but the process starts with some economic units that become “overindebted.” The following present Fisher’s argumentation in his 1932 Booms and Depressions.

Step 1: Overindebtedness and distress sales

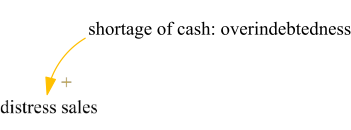

Some economic units, e.g. (non-financial) businesses, are unable to pay their debts with their available monetary assets (cash and bank accounts). This means that businesses in difficulty must find ways to sell non-monetary assets to recover enough funds to service their debts. They liquidate their inventories, sell other types of financial assets than monetary assets, and sell some superfluous real assets (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Step 1: distress sales

Note: The “+” sign means that things move in the same direction: more overindebtedness leads to more distress sales (and less overindedtedness leads to less distress sales).

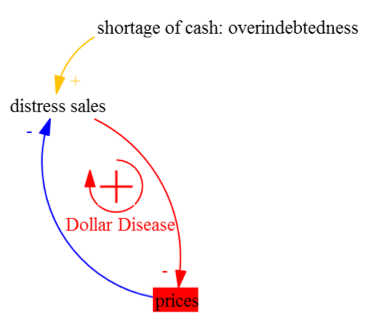

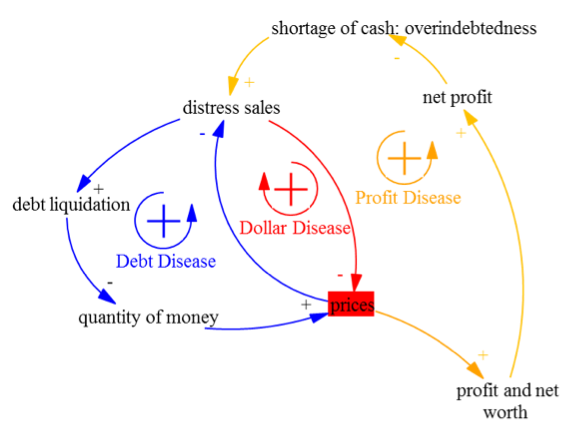

Step 2: Distress sales and deflation, the “Dollar Disease”

The sudden massive sales of non-monetary assets lead to a decline in their prices. The lower prices of assets lowers the ability of businesses to recover funds from the sales. Businesses are then forced to sell more at distress, which further pushes down prices. This is the first reinforcing feedback loop of a debt-deflation.

Figure 3. Dollar disease

Note: the sign “-“ means that things move in the opposite direction: higher distress sales lowers prices, leading to higher distress sales.

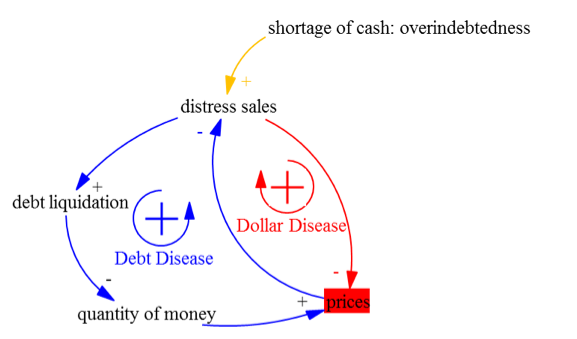

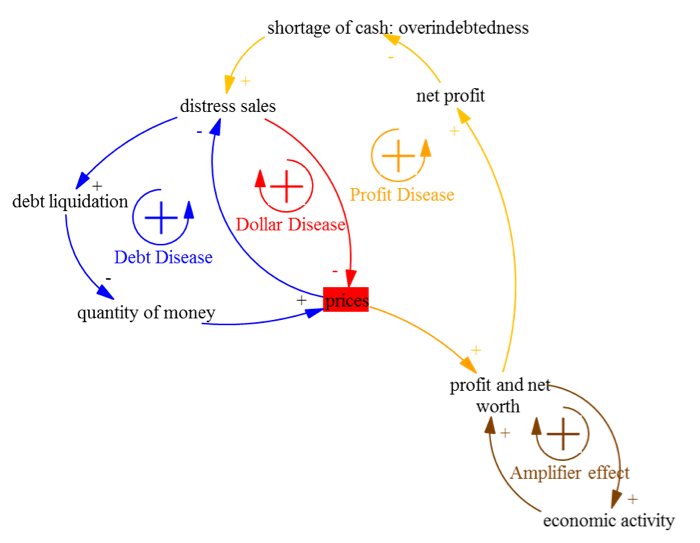

Step 3: Deflation and Debt Liquidation; The “Debt Disease”

Once they have recovered some funds, businesses service debts owed to banks and government, which reduces the money supply, and service debts owed to others (e.g. corporate bonds held by households). Some businesses may have to default and ultimately their debts are written off by creditors, which negatively impacts the creditworthiness of businesses and the net worth of creditors.

Following the quantity theory of money (which Fisher promoted), the decline in the money supply lowers prices even further, so there is a second reinforcing feedback loop: more distress sales leads to more debt liquidation, which leads to a lower quantity of money and so lower prices and then more distress sales.

Figure 4. Debt disease

Step 4: Prices and Profit and Net Worth, The “Profit Disease”

The debt and dollar diseases create a deflationary spiral that is reinforced by additional feedback loops. First, as asset prices fall, the profit from sales and net worth of business falls given everything else, which further increases their overindebtedness and so feedbacks into the dollar and debt diseases. Prices of assets fall even more.

Figure 5. Profit disease

Step 5: the “Amplifier effect”

Decline in profit and net worth means that non-financial businesses have an incentive to lay off employees. Some banks may also have to close because losses from debtors are too high to be sustained by their balance sheet. Households, who record a shrinkage of their income and prospect of unemployment, lower their consumption and may have difficulty to service their debts. Rising unemployment reduces aggregate spending, which further reduces profit and aggregate income. In addition, the declines in spending further pushes down the value of goods and services and other real assets. Now households in addition to businesses have problems to service their debts, which reinforces debt write offs and decline in the net worth of banks.

Figure 6. Amplifier effect.

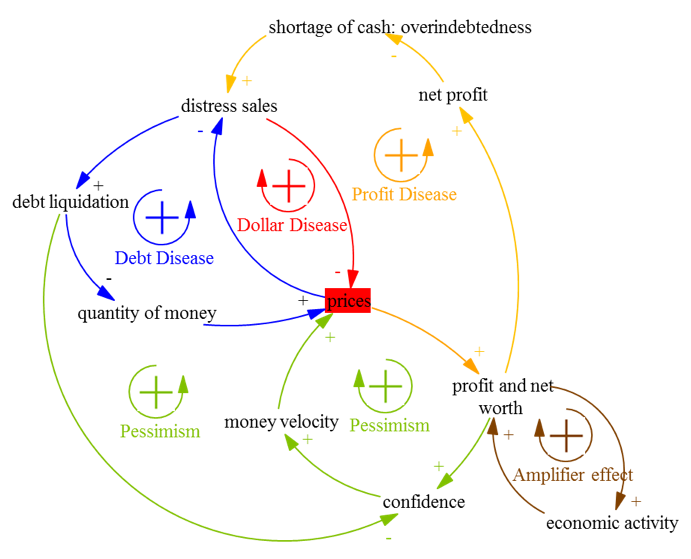

Step 6: Pessimism

As the economy records falling prices, declining economic activity, rising unemployment, rising default, and shrinking balance sheets, confidence among economic units declines and hoarding rises. Higher hoarding lowers the velocity of money and so prices are pushed further prices down (again this presentation follows the quantity theory of money). Lower confidence also decreases the willingness of banks to grant credit, and increases their willingness to hang onto their reserves to meet withdrawals, interbank payments and other dues at the lowest cost possible; the overnight interbank market freezes.

Figure 7. Confidence crisis

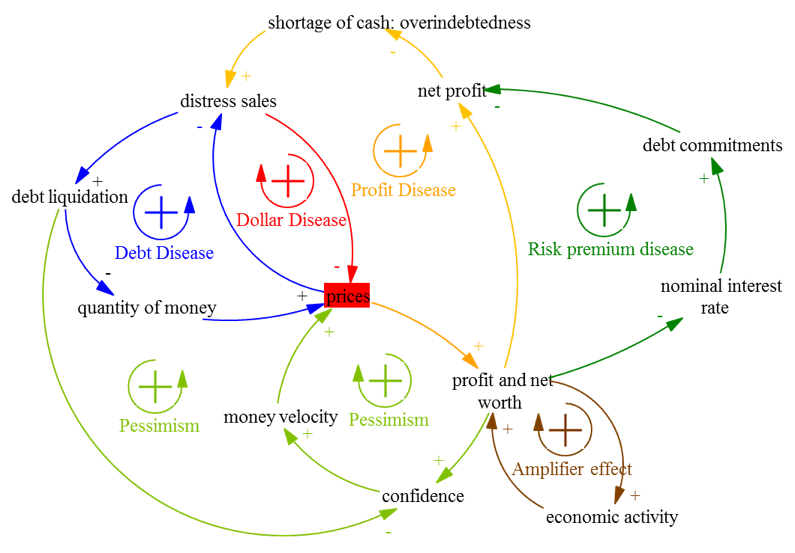

Step 7: Interest-Rate Spread

With the crisis of confidence spreading and with raging deflationary pressures and economic crisis, interest rates shoot up. This quickly spreads through the outstanding debts if interest rates on financial contracts are floating rates, which squeezes net profit (profit – debt commitments) and so increases overindebtedness.

Figure 8. Risk Premium Disease

Conclusion: Debt deflation

Overindebtedness and deflation feed on each other through several feedback loops. All these feedback loops make things worse and worse: difficulty to service debt leads to lower prices, which increases the difficulty to service debts.

If left alone a debt deflation stops only when the amount of outstanding debts has been lowered sufficiently through repayment and write offs to make the serving of debts bearable. The decline in the debt burden loosen the need for distress sales (Figure 9). Of course in the process, banks closes, households lose their savings and become unemployed, businesses close, and resources are wasted (output is left to rot, labor power and knowledge is left unused and decays quickly, capital equipment depreciates, etc.). According to market proponents this is fine because a debt deflation punishes all economic units that made “bad” decisions. Banks that overextended credits, businesses that did not satisfy their customers, households who are not flexible enough, etc. As Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon stated during the Great Depression: “liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate farmers, liquidate real estate…it will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up from less competent people.”

There are two main problems with this view. First, as explained previously, what is considered in hindsight a “bad”/incompetent decision at the time of a crisis may have been necessary prior to the crisis in order to keep up with the competition and to avoid losing market shares and income. Second, a debt deflation is not a selective process. It destroyed economic status indiscriminately by spreading through decline in net wealth, loss of job, loss of savings, decline in confidence, shut down of financing opportunities, and overall decline in economic activity. Think of a fire that starts because someone smoke in bed. This person may “deserve” to have a destroyed home but, if nothing is done to stop the fire, the entire town may be destroyed.

Figure 9. A stabilizing loop

Origins of debt deflation

While the mechanics of a debt deflation are well known and widely accepted, what causes them is subject to debate: why are economic units overindebted in the first place? Again, keeping with the distinction of previous posts on macroeconomic topics, this section makes a difference between the real exchange view and the monetary production view.

Real Exchange Economy View: Efficient Markets and Imperfections

In this view, money and finance are neutral and financial markets are efficient. The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) states that markets tend to allocate scarce resources efficiently (i.e. toward the most productive economic activities) and to allocate financial risks toward economic entities that are most able to bear them. Former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan illustrates well how the EMH is used in real world situation:

development of financial products, such as asset-backed securities, collateral loan obligations, and credit default swaps, that facilitate the dispersion of risk… These increasingly complex financial instruments have contributed to the development of a far more flexible, efficient, and hence resilient financial system than the one that existed just a quarter-century ago. (Greenspan 2005)

The EMH also states that market mechanisms tend to self-correct and to eliminate any disequilibrium such as bubbles or crashes. In order to introduce the possibility of financial crises either markets have to be imperfect, or market participants have to behave imperfectly/irrationally.

In terms of market imperfections, a lot of emphasis is put on the existence of asymmetries of information. Banks have much less information about the quality of a project than potential customers. Bankers try to protect themselves by requiring collateral. This is supposed to give an incentive to economic units who request an advance of funds to do their best to make their project successful (otherwise economic units lose the collateral).

Following a negative random shock, the value of collateral declines, which leads debtors to limit their entrepreneurial effort—because a decline in the value of the collateral means that they have less to lose by defaulting—, which increases the chances of financial difficulties. Banks take notice and start to ration credit. This, in turn, generates a credit crunch, which leads to further declines in net worth and collateral and so less effort and greater default risk.

Recent research efforts in the REE approach have focused on the reversion mechanisms (how a crisis occurs) instead of the propagation mechanisms (how a crisis spreads following a shock). Crises are endogenized by linking effort to the business cycle. The more effort individuals put into their business, the more productive they are, which leads to a greater supply of commodities and so lower prices. Lower prices lead to lower net gains, which leads to lower effort and so greater risk of default.

Given that the mathematical models developed to back this theory are all set in in real terms, and given that the random shock is one applied to the productivity of an input (e.g., land), this type of analysis applies well to a pre-capitalist agricultural economy. Nature decides which economic state occurs (good or bad weather). Financial crises are equivalent to weather calamities that decrease agricultural output.

The imperfection view can be complemented by the Monetarist view of financial crises and by the irrational approach developed by behavioral economics. The former states that financial crises are due to the incompetence of policy markers, and the latter states that behavioral imperfections of individuals contribute to the emergence of crises. People have limited cognitive capacities that restrict their capacity to acquire and interpret information, and market participants care about things that a “rational economic man” should not care about. As a consequence, a market economy is prone to bubbles, herd behaviors, cascade of information, and misallocation of resources, leading to overindebtedness and ultimately a debt deflation. One may try to correct for these behavioral problems by creating markets that provide signals that allow market participants to make the right decision.

Monetary Production Economy View: The Financial Instability Hypothesis

According to the MPE view, the previous type of analysis obviously lacks important aspects of capitalist economies. For example, government deficits do promote financial stability, which is seen as an empirical puzzle in the REE view given that deficits ought to crowd out investment and so make things worse. The REE view is also too micro-oriented and lacks a system-view of financial crises that recognize major sources of instability outside the realm of individual behavior/effort.

The Financial Instability Hypothesis (FIH) is an alternative to the EMH. The main claim of the FIH is that periods of economic stability are a fertile ground for the growth of financial fragility, i.e. the growth of the risk of debt deflation. Hyman P. Minsky, who relied on the work of Fisher, Keynes and Schumpeter, is the main developer of the FIH and provides a more detailed analysis of what “overindebtedness” means and its impacts.

Financial Fragility

According to Minsky, the degree of financial fragility of any economic unit—how badly overindebted they are—can be classified as hedge finance, speculative finance or Ponzi finance. Hedge finance means that an economic unit is expected to be able to meet its liability commitments with the net cash flow it generates from its routine economic operations (work for most individuals, profit from going concern for companies) and monetary balances. Even though indebtedness may be high (even relative to income), an economy in which most economic units rely on Hedge finance is not prone to debt deflation, unless unusually large declines in routine cash inflows and/or unusually large increases in cash outflows occur. Even then, monetary savings are usually available in a large enough amount to provide a buffer against unforeseen problems. As such, it is not expected that the servicing of debts will be problematic and so no refinancing (going into debt to service existing debts) and/or sales of non-monetary assets is expected.

Speculative finance means that routine net cash flow sources and monetary balances are expected to be sufficient to pay the income component (interest, dividend, among others) but too low to pay the capital component (debt principal, margin calls, cash withdrawals, among others) of liabilities. As a consequence, an economic unit needs either to go into debt or to sell some non-monetary assets in order to service the principal due. Economic units usually expect that rolling debt over will be possible instead of liquidating assets. The length of time during which routine cash flows are expected to fall short of capital repayment depends on the economic unit. The business model of banks is such that refinancing is usually needed to service the capital component of liabilities, as such banking requires a reliable and cheap refinancing source. Other businesses may only have a temporary need to roll over their debts.

Ponzi finance, also called interest-capitalization finance, means that an economic unit is not expected to generate enough net cash flow from its routine economic operations, nor to have enough monetary savings to pay the capital and income service due on outstanding financial contracts. As a consequence, in order to service a given level of outstanding debts, Ponzi finance relies on the growing availability of refinancing sources, and/or an expected liquidation of non-monetary assets at rising prices. At the microeconomic level, an economic unit that uses Ponzi finance to fund its assets is highly financially fragile. At the macroeconomic level, if key economic units behind the growth of the economy are involved in Ponzi finance, the economic system is highly prone to a debt deflation.

Note that this categorization is not merely a measure of the use of external funding, i.e. of the size of leverage; but also, a measure of the quality of the leverage. At the core of this analytical categorization is an analysis of the means that are expected to be used to fulfill financial contracts. Hedge finance is not expected to require any refinancing operation or liquidation of non-monetary assets to service debts; Ponzi finance requires a growing use of refinancing and liquidation to service debts. This has important regulatory implications as explained previously, because knowing HOW one can service debt because as important, if not more important, than knowing IF one can service debts: low default probability (IF) does not mean low financial fragility (HOW).

Ponzi finance should be differentiated from the existence or not of a “bubble.” The categorization does not aim at measuring the accuracy (however, defined) of the price of assets used to service debts. Ponzi finance is a more important concept than bubbles for the purpose of economic stability. Ponzi finance means that leverage and asset prices end up going up together and feed on each other on the upside. Higher leverage requires higher collateral value and so higher asset prices, and the funding of assets at a price that grows faster than income rises requires higher leverage. This is the crucial dynamic regardless of the correctness of the value of asset prices because, bubble or not, the size of a potential debt deflation grows with the duration of the use of Ponzi finance. Without Ponzi finance there cannot be a debt deflation because there is no leverage involved in the asset-price appreciation. Without a debt inflation, there cannot be a debt deflation.

Ponzi finance is also different from fraud (which can prevail at hedge, speculative or Ponzi stage). Ponzi finance is an unsustainable financial process regardless of the legality of a financial structure. Indeed, in order to persist it requires an exponential growth of financial participation, which is not possible because, ultimately, there is a limited number of economic agents that can or will participate.

The H/S/P categorization does not apply to monetarily sovereign governments, i.e. governments that issue their own nonconvertible currency and that issue public debt denominated in their currency. Examples of monetarily sovereign governments are the United States Federal Government, the Japanese National Government, the United Kingdom National Government, the Chinese and Mexican Central Governments. Examples of non-monetarily sovereign governments are national governments of the Eurozone, the United States under the gold standard before 1933, state and local governments in the United States and, any country that issues securities denominated in a foreign currency. When a government is monetarily sovereign, it has a monopoly over the currency supply and so always can meet payments denominated in its currency as they come due. Hedge finance applies to all sovereign government that issues its own currencies. In addition, the federal government may provide bonds and other default-free liquid securities that boost the liquidity of the balance sheets of the private sector. The long period of financial stability in the United States after World War II was the result of highly liquid balance sheets in the private sector due to large government deficits during World War II that flooded the private sector with safe assets.

The Financial Instability Hypothesis

According to the FIH, during a period of prolonged expansion, the proportion of economic units involved in speculative and Ponzi finance grows, and so the risk of a debt deflation increases. The period of expansion may record minor recessions—e.g., the 1991 and 2000 downturns in the United States—that do not significantly tame the state of expectation of private economic units and so do not significantly make underwriting practices more prudent (so the FIH is not a theory of the business cycle but rather focuses one what causes significant downturns).

Contrary to the behavioral explanation, irrationality is not at the heart of instability. The boom, with its mania, just amplifies the dynamics that emerged previously during a period of prolonged expansion. Contrary to the market imperfection explanation, market mechanisms promote instability not stability. The heart of the problem is not found in individuals making dumb decisions but rather in the system in which they operate. Capitalism is a much more financially unstable economic system than those that previously existed. Capitalism incentives and mechanics push economic units into Ponzi finance.

There are several channels through which financial fragility grows and they have to do with anything that changes the relation between income and debt service. Anything that pushes an economic unit from a case where income is greater than debt service to a case where income is less than debt service. This can happen either because income level (or growth) falls and/or debt service level (or growth) rises. Factors that impacts both are described briefly:

- Structural causes:

- Banks are speculative units: the maturity of banks’ liabilities is short relative to maturity of banks’ asset so they need to refinance all the time. Banks aim at lowering maturity of their assets to limit the maturity mismatch, which promotes speculative finance in non-bank sector. For example, in the US, the 30-year mortgages is not a product of private banking but of government intervention, and it must be subsidized to persist. Banks much prefer at shorter-term mortgages (say 10 years) that require households to refinance, which creates a dependence on the direction of home prices (if home prices fall refinancing may not happen).

- Change in the banking business: move away from the originate-and-hold model to the originate-and-distribute model, which create adverse incentives in terms of underwriting and debt reworking.

- Economic causes

- Search for profit and market share, and market saturation: ROE = ROA x leverage.

- Inequalities: the need to use debt to sustain a given standard of leaving has increased (student debt, healthcare debt, etc.)

- Unexpected events: The FIH leaves some room for adverse random shocks (say a hurricane destroyed many houses and businesses, which triggers massive payments by insurance companies)

- Policy reasons:

- Deregulation, desupervision and deenforcement: fraud grows and underwriting worsens.

- Fiscal policy: A period of prolonged expansion that is led by a monetarily sovereign government will not lead to financial instability. Fiscal deficits boost macroeconomic profit and personal savings and provides cash flows as well as safe financial assets to the private sector. However, as shown in the previous post, government’s willingness to reach a surplus, combined with the automatic stabilizers, means that non-government sectors may be forced to deficit spend.

- Monetary Policy: During a period of expansion, the central bank raises interest rates and that increases the debt burden. Minsky is of the opinion that fine tuning and preserving financial stability are not compatible and argues for a central bank that focuses on financial stability.

- Socio-psychological reasons

- Long period of prosperity leads to a decline in risk perception because economic news is good and it is too costly to look too much backward.

- Uncertainty means that economic units rely on norms to make decisions. These norms are rationalized through a convention, which is mental construction about the current economic trends and about what to expect (think new economy/era convention). There is a strong incentive to stick to the convention to avoid losing market share or avoid drawing attention of regulators. So if Ponzi finance is considered normal, a bank will do it to avoid losing market shares and profit, and will find comfort in the fact that “everybody else is doing it so it is ok.”

How to deal with financial crises

Financial crises that are severe create a lot of damages if they are not managed through government intervention. This government intervention involved both quick fixes to deal with the immediate problems and long-term policies to prevent moral hazard and promote stability. The recent responses to the Great Recession provide examples of what not to do:

- Stop the liquidity crisis: central bank provide funds at penalty rate, against safe collateral, to solvent institutions. One may argue that, during a crisis, a lot of financial assets that previously looked safe may now be unsafe because of the lack of confidence and because of poor economic prospects. For example, prime mortgagees may default because they lost their job. There is a way around this issue. Central banks should accept only financial assets that were created by following strict underwriting, that is, those that involved hedge finance and speculative finance prior to the crisis. Central banks may record losses on them given that a debt deflation impacts even economic units with strong creditworthiness, but that should be minimal. Do not provide liquidity against Ponzi finance inducing financial instruments.

- Recent crisis: Fed provided advances at near 0% rate, against poor to toxic collateral (accepted at par), to questionable institutions, to non-bank entities

- Stop the solvency crisis: Bank holiday to examine the books of financial institutions in details for a given period of time (say a week like during the Great Depression) and close insolvent banks. Act to sustain income and lower debt burden. Lower the debt burden by reworking debts of economic units who would be solvent with the reworking (during the great depression, government bought interest-only mortgages from banks and replace them with 30-year fixed rate mortgages). To sustain income, large-scale long-term fiscal policy such as a job guarantee program (great depression work programs were started in matters of days).

- Recent crisis: no significant analysis of books (only 2 Fed people sent at Lehman brothers, superficial stress test), insignificant and slow fiscal action to stabilize income (700 billion was not enough and was implemented over years), hide losses of financial institutions by widening level-3 valuation (aka mark-to-model), injection of capital in banks via Treasury without any real congressional oversight, no significant reworking of debts on non-bank agents.

- Change incentives and regulation, supervise and enforce: prosecute top managers for fraud, cease and desist orders, major reworking of regulation and supervision to deal with problems, promote hedge finance and if necessary forbid Ponzi finance.

- Recent crisis: Not a single prosecution of top executives even though fraud is obvious (ask FBI, and rating agencies that finally had a look at mortgage contracts), civil instead of criminal cases (the financial institution pays fines and promises not do it again), no major reregulatory trends, no enforcement of existing laws prior and during crisis.

Even though a financial system may be on the brinks of collapse and panic is generalized, regulatory must follow the law. If necessary, regulators may use emergency executive powers (bank holiday) to shut down the financial system temporarily and get to the bottom of the problem. Lenience will lead to long-term instability because the existence of government safety net promotes moral hazard. Without safety net, such as a central bank acting as lender of last resort, economic crises would be very severe.

To go further: Ponzi finance and the balance sheet

When an economic unit is involved in Ponzi finance, it has to go into debt to service principal AND interest. Say that there is a balance of $100 on a credit card that represent expenses for the month and that there is also $10 of interest due. To service the credit card debt, one must open a new credit card to pay $110 due on credit card #1. The following month $110 + $11 of interest is due on the second credit card. The amount of financial liabilities grows. Another way to service credit card #1 is to sell some assets worth $110. So Ponzi finance implies that net financial accumulation (NFA) declines because either financial asset falls or financial liability rises. We know that NFA is related to net wealth:

ΔNW = ΔRA + NFA

Given everything else, Ponzi finance leads to a fall in net worth. There are two ways to mitigate this decline:

- Overtime the assets funded in a Ponzi way may start to generate enough cash flow to cover debt service. Say that a company was just created and needs some time to get its business to earn an income. In the meantime, it needs financing to pay employees, get the business set up, etc. During that time, the net worth of the company will fall but it is expected that ultimately the business will be profitable and generate enough cash flow to pay creditors. One may call this income-based Ponzi finance: for a while income is insufficient but there is an expectation that this is only temporary.

- The price of real assets and the price of financial assets that are still on the balance sheet go up fast enough to more than offset the rise in debt and the liquidation of assets. The recent housing boom that allowed households to record massive increase in net worth while they were going massively into debt is an example of such dynamics. The underwriting worsened so much that the only way to make a mortgage profitable was to sell the house at a high enough price to cover interest and other payment due to creditors. One may call that asset-based Ponzi finance, or pyramid scheme: there is no expectation that income will ever be enough to service debt, the liquidation of the collateral and other assets is the only expected means to make the Ponzi financing profitable and to keep net worth rising.

To go even further: Income vs. Cash inflow

In most presentation of the FIH, income and cash inflow are not distinguished carefully. For example, the FIH is often presented from the point of view of the business sector with profit (U) reflecting the ability or not to fulfill debt service (DS) so that U > DS is hedge finance. At the macroeconomic level, U is determined by the Kalecki equation of profit.

At the theoretical level that may be good enough but not at the empirical level. Income and cash flows are two different things. Income is about measuring gains in net worth, cash flow is about measuring change in monetary assets. The Kalecki equation of profit does not say anything about monetary gains, i.e. gains of monetary assets. For example, an increase in unsold inventories raises profit because higher inventories increase real assets. Similarly for households, personal income includes quite a few items that are unrelated to monetary gains. Vegetables grown in the garden, service provided by owning a house, among other things, are counted as imputed income. Unfortunately, creditors demand monetary payments so earning an income in real terms does not help to service debts.

What is really important is what Minsky called the “cash box condition” and expectations based on it: how cash inflows plus monetary balances compare to cash outflows now and in the future? That may or may not be related to profit and personal income. The cash-flow statement, rather than the income statement, together with the expectation embedded in financial contracts, give a better idea of the financial fragility of an economic unit.

That’s it for today! We are done with macroeconomic topics. Next is the final topic of this series: Money! Money! Money! Moooneeyy!