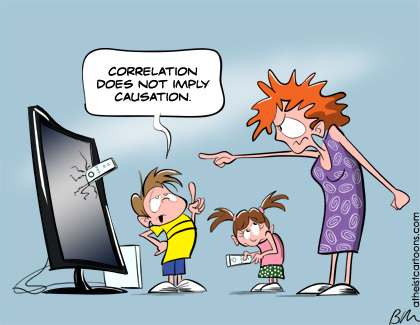

The limits of statistical inference Causality in social sciences — and economics — can never solely be a question of statistical inference. Causality entails more than predictability, and to really in depth explain social phenomena require theory. Analysis of variation — the foundation of all econometrics — can never in itself reveal how these variations are brought about. First when we are able to tie actions, processes or structures to the statistical relations detected, can we say that we are getting at relevant explanations of causation. Most facts have many different, possible, alternative explanations, but we want to find the best of all contrastive (since all real explanation takes place relative to a set of alternatives) explanations. So which is the best explanation? Many scientists, influenced by statistical reasoning, think that the likeliest explanation is the best explanation. But the likelihood of x is not in itself a strong argument for thinking it explains y. I would rather argue that what makes one explanation better than another are things like aiming for and finding powerful, deep, causal, features and mechanisms that we have warranted and justified reasons to believe in. Statistical — especially the variety based on a Bayesian epistemology — reasoning generally has no room for these kind of explanatory considerations.

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

The limits of statistical inference

Causality in social sciences — and economics — can never solely be a question of statistical inference. Causality entails more than predictability, and to really in depth explain social phenomena require theory. Analysis of variation — the foundation of all econometrics — can never in itself reveal how these variations are brought about. First when we are able to tie actions, processes or structures to the statistical relations detected, can we say that we are getting at relevant explanations of causation.

Causality in social sciences — and economics — can never solely be a question of statistical inference. Causality entails more than predictability, and to really in depth explain social phenomena require theory. Analysis of variation — the foundation of all econometrics — can never in itself reveal how these variations are brought about. First when we are able to tie actions, processes or structures to the statistical relations detected, can we say that we are getting at relevant explanations of causation.

Most facts have many different, possible, alternative explanations, but we want to find the best of all contrastive (since all real explanation takes place relative to a set of alternatives) explanations. So which is the best explanation? Many scientists, influenced by statistical reasoning, think that the likeliest explanation is the best explanation. But the likelihood of x is not in itself a strong argument for thinking it explains y. I would rather argue that what makes one explanation better than another are things like aiming for and finding powerful, deep, causal, features and mechanisms that we have warranted and justified reasons to believe in. Statistical — especially the variety based on a Bayesian epistemology — reasoning generally has no room for these kind of explanatory considerations. The only thing that matters is the probabilistic relation between evidence and hypothesis. That is also one of the main reasons I find abduction — inference to the best explanation — a better description and account of what constitute actual scientific reasoning and inferences.

For more on these issues — see the chapter “Capturing causality in economics and the limits of statistical inference” in my On the use and misuse of theories and models in economics.