Read my lips — regression analysis does not imply causation Many treatments of regression seem to take for granted that the investigator knows the relevant variables, their causal order, and the functional form of the relationships among them; measurements of the independent variables are assumed to be without error. Indeed, Gauss developed and used regression in physical science contexts where these conditions hold, at least to a very good approximation. Today, the textbook theorems that justify regression are proved on the basis of such assumptions. In the social sciences, the situation seems quite different. Regression is used to discover relationships or to disentangle cause and effect.Ho wever, investigators have only vague ideas as to the relevant variables and their causal order; functional forms are chosen on the basis of convenience or familiarity; serious problems of measurement are often encountered. Regression may offer useful ways of summarizing the data and making predictions. Investigators may be able to use summaries and predictions to draw substantive conclusions. However, I see no cases in which regression equations, let alone the more complex methods, have succeeded as engines for discovering causal relationships … The larger problem remains.

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

Read my lips — regression analysis does not imply causation

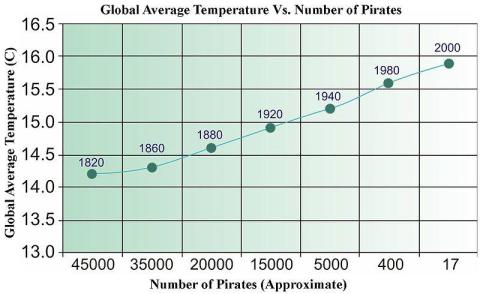

Many treatments of regression seem to take for granted that the investigator knows the relevant variables, their causal order, and the functional form of the relationships among them; measurements of the independent variables are assumed to be without error. Indeed, Gauss developed and used regression in physical science contexts where these conditions hold, at least to a very good approximation. Today, the textbook theorems that justify regression are proved on the basis of such assumptions.

In the social sciences, the situation seems quite different. Regression is used to discover relationships or to disentangle cause and effect.Ho wever, investigators have only vague ideas as to the relevant variables and their causal order; functional forms are chosen on the basis of convenience or familiarity; serious problems of measurement are often encountered.

Regression may offer useful ways of summarizing the data and making predictions. Investigators may be able to use summaries and predictions to draw substantive conclusions. However, I see no cases in which regression equations, let alone the more complex methods, have succeeded as engines for discovering causal relationships …

The larger problem remains. Can quantitative social scientists infer causality by applying statistical technology to correlation matrices? That is not a mathematical question, because the answer turns on the way the world is put together. As I read the record, correlational methods have not delivered the goods. We need to work on measurement, design, theory. Fancier statistics are not likely to help much.

If you only have time to study one mathematical statistician, the choice should be easy — David Freedman.