In this post I will explore Keynes’ theory of the business cycle. He discusses his views in Chapter 22 of the General Theory and I think they hold up pretty well today. At the beginning of the chapter he notes that the business cycle — so-called, because it is not really a “cycle” at all despite what Keynes says in the chapter — is a highly complex phenomenon and that we can only really glean some very general features of it. Keynes opens with a very clear quote on what he thinks to be the key determinate: The Trade Cycle is best regarded, I think, as being occasioned by a cyclical change in the marginal efficiency of capital, though complicated. and often aggravated by associated changes in the other significant short-period variables of the economic system. Recall that the

Topics:

Philip Pilkington considers the following as important: Economic Theory

This could be interesting, too:

Luiza Nassif Pires writes Increasing Diversity in Economics Is Not Only a Moral Obligation

Luiza Nassif Pires writes Increasing Diversity in Economics Is Not Only a Moral Obligation

Mike Norman writes Timothy Taylor — US Not the Source of China’s Growth, China Not the Source of America’s Problems

Mike Norman writes Peter Radford — A Little Knowledge

In this post I will explore Keynes’ theory of the business cycle. He discusses his views in Chapter 22 of the General Theory and I think they hold up pretty well today. At the beginning of the chapter he notes that the business cycle — so-called, because it is not really a “cycle” at all despite what Keynes says in the chapter — is a highly complex phenomenon and that we can only really glean some very general features of it.

Keynes opens with a very clear quote on what he thinks to be the key determinate:

The Trade Cycle is best regarded, I think, as being occasioned by a cyclical change in the marginal efficiency of capital, though complicated. and often aggravated by associated changes in the other significant short-period variables of the economic system.

Recall that the marginal efficiency of capital (MEC) is basically the expected profitability that investors think they will receive on their investments measured against the present cost of these investments. The key component in the MEC is, of course, investor expectations. Keynes is clear on this and distinguishes himself from those who claim that a rise in the rate of interest is the cause of the crisis. He writes:

Now, we have been accustomed in explaining the “crisis” to lay stress on the rising tendency of the rate of interest under the influence of the increased demand for money both for trade and speculative purposes. At times this factor may certainly play an aggravating and, occasionally perhaps, an initiating part. But I suggest that a more typical, and often the predominant, explanation of the crisis is, not primarily a rise in the rate of interest, but a sudden collapse in the marginal efficiency of capital.

This is extremely perceptive and, I think, entirely correct. A rise in the rate of interest will typically precipitate a recession. In the US, for example, it is well-known that when the short-term rate of interest rises above the long-term rate of interest (i.e. when the yield curve is inverted) there will likely be a recession. (This is probably not, however, the case in other countries).

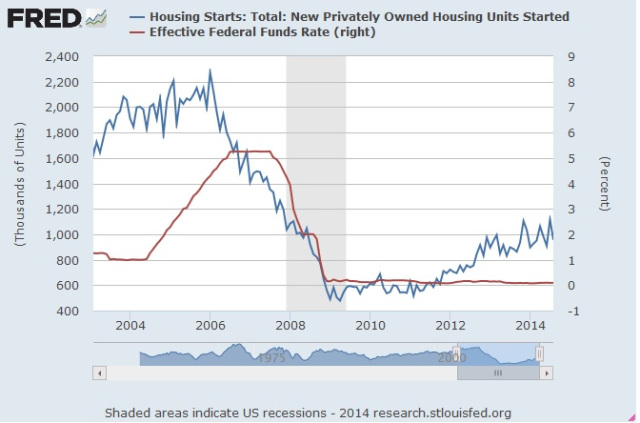

But the actual cause of the crisis is, as Keynes says, a collapse in the MEC. Consider the case of the 2008 recession. This recession was initiated by a fall in house prices which led to a fall in housing construction. Below is the number of housing starts plotted against the interest rate.

Now Keynes would argue that the causal chain went as follows: interest rates began to rise => the MEC of investors began to fall => eventually the MEC reached a threshold point at which investors stopped building houses. A recession ensued.

Now Keynes would argue that the causal chain went as follows: interest rates began to rise => the MEC of investors began to fall => eventually the MEC reached a threshold point at which investors stopped building houses. A recession ensued.

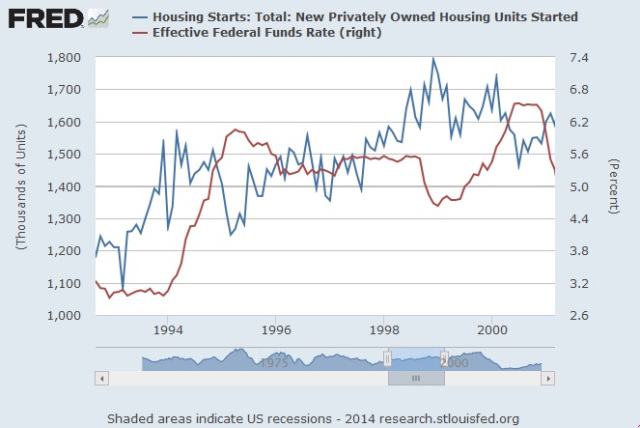

This is extremely important because the alternative interpretation is that the interest rate reached a point that it choked off credit demand for new housing. But this is not empirically valid. Take a look at the following chart plotting the same variables in the 1990s.

In this period we see interest rates rise continuously — and, what is more, from a higher base — and yet housing continues to rise in lockstep. Clearly there is no mechanical relationship between housing starts and the interest rate. So, Keynes’ interpretation bears out: for some reason — and we shall not get into it here because it is very complicated — but for some reason in 2006 the interest rate rises triggered a collapse of the MEC among home-builders.

What happens next? Keynes says that liquidity preference shoots up quickly after the MEC collapses, the economy enters recession and the capital markets get nervous. He writes:

The fact that a collapse in the marginal efficiency of capital tends to be associated with a rise in the rate of interest may seriously aggravate the decline in investment. But the essence of the situation is to be found, nevertheless, in the collapse in the marginal efficiency of capital, particularly in the case of those types of capital which have been contributing most to the previous phase of heavy new investment. Liquidity-preference, except those manifestations of it which are associated with increasing trade and speculation, does not increase until after the collapse in the marginal efficiency of capital.

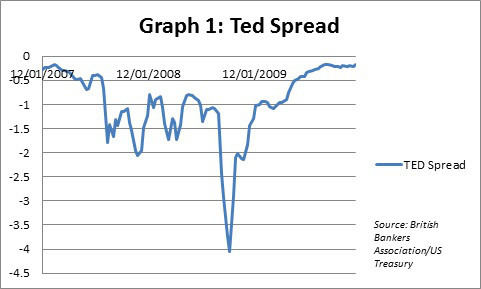

The effects of this are actually more difficult to perceive today than they were in Keynes’ time. Today central banks will step in and quickly flood the capital markets with liquidity when liquidity preference rises. Nevertheless, in extreme cases — such as a liquidity trap proper when the central bank loses control of interest rates — we will indeed see liquidity preference rise and interest rates on risky assets shoot up. This is precisely the case in 2008. Here is a graph showing interest rates on interbank loans shoot up vis-a-vis highly liquid treasury bills (which are money substitutes).

Keynes is quick to emphasise that monetary policy alone will ease interest rates and this may help recovery, but it will not actually provoke the recovery. He writes:

Keynes is quick to emphasise that monetary policy alone will ease interest rates and this may help recovery, but it will not actually provoke the recovery. He writes:

It is this, indeed, which renders the slump so intractable. Later on, a decline in the rate of interest will be a great aid to recovery and, probably, a necessary condition of it. But, for the moment, the collapse in the marginal efficiency of capital may be so complete that no practicable reduction in the rate of interest will be enough. If a reduction in the rate of interest was capable of proving an effective remedy by itself, it might be possible to achieve a recovery without the elapse of any considerable interval of time and by means more or less directly under the control of the monetary authority. But, in fact, this is not usually the case; and it is not so easy to revive the marginal efficiency of capital, determined, as it is, by the uncontrollable and disobedient psychology of the business world. It is the return of confidence, to speak in ordinary language, which is so insusceptible to control in an economy of individualistic capitalism. This is the aspect of the slump which bankers and business men have been right in emphasising, and which the economists who have put their faith in a “purely monetary” remedy have underestimated.

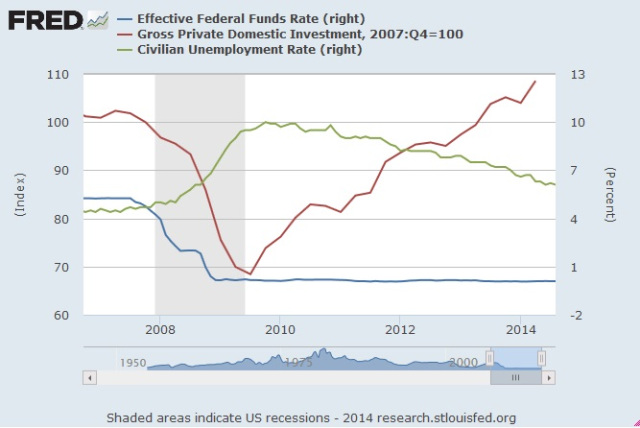

Again, if we turn to the data from the 2008 slump this will prove the case beyond a shadow of a doubt. The following graph maps gross private investment, the unemployment rate and the central bank interest rate.

Meanwhile in the background the government deficit opened up massively and Congress passed a massive stimulus plan. After this investment picked up — very slowly — and unemployment started to fall — again, slowly. Because the stimulus spending did not plug the investment gap after six years we are still not back where we were in 2008 in terms of employment and investment has just about clawed back its losses.

Some will point to previous recessions where the interest rate was lowered and investment shot up as proof that monetary alone might be sufficient to steer the economy. I would say to them: take a look at the government budget balance. In all the post-war recessions the budget balance opened up — usually through the automatic stabilisers — and it was this that propped up demand. In absence of this some of these recessions would likely have become depressions.

Keynes is aware that the Austrians might pick up on his theory and then add their own ideologically motivated analyses of what constitutes ‘good’ and ‘bad’ investments. He makes clear something that I have tried to emphasise in a paper that I will be publishing shortly: we cannot say that the private sector will allocate resources effectively if left alone because they are subject to irrational swings of mood and do not engage in rational calculations as the marginalists (and Austrians) assume.

It may, of course, be the case — indeed it is likely to be — that the illusions of the boom cause particular types of capital-assets to be produced in such excessive abundance that some part of the output is, on any criterion, a waste of resources; — which sometimes happens, we may add, even when there is no boom. It leads, that is to say, to misdirected investment. But over and above this it is an essential characteristic of the boom that investments which will in fact yield, say, 2 per cent. in conditions of full employment are made in the expectation of a yield of, say, 6 per cent., and are valued accordingly. When the disillusion comes, this expectation is replaced by a contrary “error of pessimism”, with the result that the investments, which would in fact yield 2 per cent. in conditions of full employment, are expected to yield less than nothing; and the resulting collapse of new investment then leads to a state of unemployment in which the investments, which would have yielded 2 per cent. in conditions of full employment, in fact yield less than nothing. We reach a condition where there is a shortage of houses, but where nevertheless no one can afford to live in the houses that there are.

The final point we should bring out is the policy implications of this. Keynes favours that the central bank holds down the rate of interest and the government maintains full employment throughout the cycle. He writes:

Thus the remedy for the boom is not a higher rate of interest but a lower rate of interest! For that may enable the so-called boom to last. The right remedy for the trade cycle is not to be found in abolishing booms and thus keeping us permanently in a semi-slump; but in abolishing slumps and thus keeping us permanently in a quasi-boom.

I think that this is overly simplistic but certainly on the right track. We can hold down the general rate of interest so that money is cheap but then have the central bank exercise control particular rates of interest in markets prone to speculative bubbles by using Tom Palley’s ABRR proposal. In this scheme the central bank controls overactive investment markets but does not really hold responsibility for ensuring that economic growth be maintained continuously. That is the role of fiscal policy.

Personally I think that democracies are seriously flawed and politicians generally stupid and short-sighted. For this reason I would recommend building institutions that automatically open up the fiscal deficit in times of unemployment. Many welfare state institutions do exactly that — and we have these institutions, not politicians, to thank for ensuring that we have not entered a serious depression between 1980 and today. My favourite of such institutions is the Job Guarantee program developed and supported by Abba Lerner, Hyman Minsky and the Modern Monetary Theorists. But I recognise that this should be an open debate.