From David Ruccio The U.S. economy is a remarkable success according to the standards of neoclassical economic theory. Yet, for “prime-age” men, who need to work to provide for themselves and their families, it is increasingly a failure. That’s the clear lesson from the latest report from the Council of Economic Advisors (pdf) on “The Long-Term Decline in Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation” (which has been taken up and discussed in a wide variety of news media, from the Financial Times [ht: bn] to the New York Times). On one hand, the United States, more than any other advanced country, has labor market institutions that represent a neoclassical economist’s free-market dream. The United States has the lowest level of labor market regulation, the fewest employment protections, the third-lowest minimum cost of labor, and among the lowest rates of collective bargaining coverage among OECD countries. . .In the United States, governments and institutions (such as labor unions) place relatively few barriers in the way of employers who want to change who they employ and what they pay. That’s exactly what labor markets look like in neoclassical models and what neoclassical economists recommend as the best, “flexible” labor-market policy.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

The U.S. economy is a remarkable success according to the standards of neoclassical economic theory. Yet, for “prime-age” men, who need to work to provide for themselves and their families, it is increasingly a failure.

That’s the clear lesson from the latest report from the Council of Economic Advisors (pdf) on “The Long-Term Decline in Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation” (which has been taken up and discussed in a wide variety of news media, from the Financial Times [ht: bn] to the New York Times).

On one hand, the United States, more than any other advanced country, has labor market institutions that represent a neoclassical economist’s free-market dream.

The United States has the lowest level of labor market regulation, the fewest employment protections, the third-lowest minimum cost of labor, and among the lowest rates of collective bargaining coverage among OECD countries. . .In the United States, governments and institutions (such as labor unions) place relatively few barriers in the way of employers who want to change who they employ and what they pay.

That’s exactly what labor markets look like in neoclassical models and what neoclassical economists recommend as the best, “flexible” labor-market policy. It’s a world in which it’s easy to hire and fire workers, which is supposed to facilitate matches between employers who want profits and individuals who want to work.

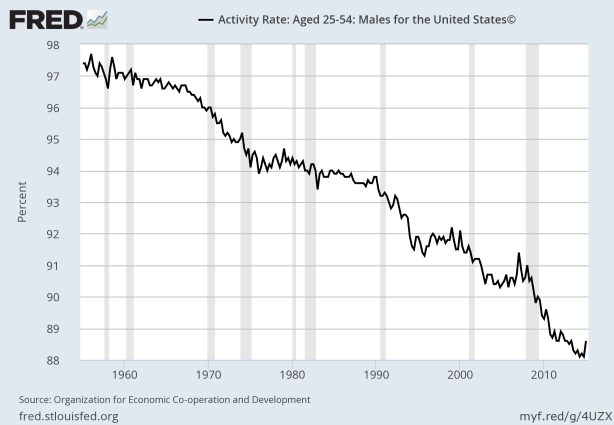

And yet, on the other hand, the labor-force participation rate of men between the ages of 225 and 54 has been declining since the late-1950s—from a peak of 98 percent to close to 88 percent today (which means the United States now ranks third lowest, above only Israel and Italy, among 34 OECD nations). And the rate for men with a high-school degree or less had plummeted even more, to 83 percent.

In a world in which selling their ability to labor is the principal way for workers to earn enough income to purchase the commodities necessary to support themselves and their families, the extraordinary success in creating neoclassical labor markets in the United States has resulted in a complete failure from the perspective of working people. As a result of declining wages (and, in addition, high incarceration rates, which makes finding a job that much more difficult), prime-age men are simply being forced by employers to drop out of the labor force.*

Now, the decrease in the labor-force participation rate for male workers has not escaped the attention of other mainstream economists and policymakers, as the long-run decline has tremendous implications for economic growth.** Fewer workers (especially since the labor-force participation rate for prime-age women, which had been increasing, leveled off after 1990 and since 2000 has also started to decline) means, in the absence of large productivity gains, less output and slower rates of growth. Therefore, they propose policies that seek to create more flexibility for prime-age men and women within the labor market, to increase their labor-force participation rates.

The alternative, of course, is to create more flexibility for workers outside the labor market—by giving them more say in the enterprises where they work and by creating a universal basic income for all—so that they’re no longer forced to have the freedom to sell their ability to work to a small group of employers.

That kind of flexibility beyond the labor market represents the only real way of solving the failures of neoclassical economists and of the economic and social system they celebrate.

*As the report notes, “The direct effect of increased incarceration is to actually increase the reported participation rate because the official statistics cover only the non-institutionalized population and omit prisoners, people in long-term care, and active duty members of the Armed Services.” But the indirect effect runs in the opposite direction, as these men face substantially lower demand for their labor after they are released from prison.

**Even the International Monetary Fund has recently warned about the negative implications for U.S. economic growth of declining labor force participation—along with slow productivity growth, an increasingly polarized society with income gains concentrated among the wealthiest Americans, and too many people living in poverty.