From David Ruccio Back in 2010, Charles Ferguson, the director of Inside Job, exposed the failure of prominent mainstream economists who wrote about and spoke on matters of economic policy to disclose their conflicts of interest in the lead-up to the crash of 2007-08. Reuters followed up by publishing a special report on the lack of a clear standard of disclosure for economists and other academics who testified before the Senate Banking Committee and the House Financial Services Committee between late 2008 and early 2010, as lawmakers debated the biggest overhaul of financial regulation since the 1930s. Well, economists are still at it, leveraging their academic prestige with secret reports justifying corporate concentration. That’s according to a new report from ProPublica: If the government ends up approving the billion AT&T-Time Warner merger, credit won’t necessarily belong to the executives, bankers, lawyers, and lobbyists pushing for the deal. More likely, it will be due to the professors. A serial acquirer, AT&T must persuade the government to allow every major deal. Again and again, the company has relied on economists from America’s top universities to make its case before the Justice Department or the Federal Trade Commission.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Back in 2010, Charles Ferguson, the director of Inside Job, exposed the failure of prominent mainstream economists who wrote about and spoke on matters of economic policy to disclose their conflicts of interest in the lead-up to the crash of 2007-08. Reuters followed up by publishing a special report on the lack of a clear standard of disclosure for economists and other academics who testified before the Senate Banking Committee and the House Financial Services Committee between late 2008 and early 2010, as lawmakers debated the biggest overhaul of financial regulation since the 1930s.

Well, economists are still at it, leveraging their academic prestige with secret reports justifying corporate concentration.

That’s according to a new report from ProPublica:

If the government ends up approving the $85 billion AT&T-Time Warner merger, credit won’t necessarily belong to the executives, bankers, lawyers, and lobbyists pushing for the deal. More likely, it will be due to the professors.

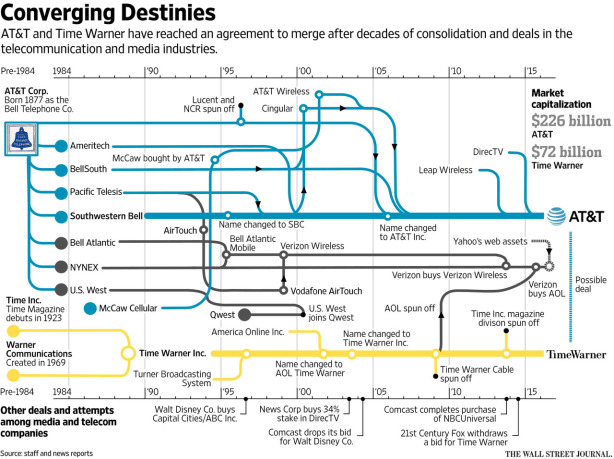

A serial acquirer, AT&T must persuade the government to allow every major deal. Again and again, the company has relied on economists from America’s top universities to make its case before the Justice Department or the Federal Trade Commission. Moonlighting for a consulting firm named Compass Lexecon, they represented AT&T when it bought Centennial, DirecTV, and Leap Wireless; and when it tried unsuccessfully to absorb T-Mobile. And now AT&T and Time Warner have hired three top Compass Lexecon economists to counter criticism that the giant deal would harm consumers and concentrate too much media power in one company.

Today, “in front of the government, in many cases the most important advocate is the economist and lawyers come second,” said James Denvir, an antitrust lawyer at Boies, Schiller.

Economists who specialize in antitrust — affiliated with Chicago, Harvard, Princeton, the University of California, Berkeley, and other prestigious universities — reshaped their field through scholarly work showing that mergers create efficiencies of scale that benefit consumers. But they reap their most lucrative paydays by lending their academic authority to mergers their corporate clients propose. Corporate lawyers hire them from Compass Lexecon and half a dozen other firms to sway the government by documenting that a merger won’t be “anti-competitive”: in other words, that it won’t raise retail prices, stifle innovation, or restrict product offerings. Their optimistic forecasts, though, often turn out to be wrong, and the mergers they champion may be hurting the economy.

Right now, the United States is experiencing a wave of corporate mergers and acquisitions, leading to increasing levels of concentration, reminiscent of the first Gilded Age. And, according to ProPublica, a small number of hired guns from economics—who routinely move through the revolving door between government and corporate consulting—have written reports for and testified in favor of dozens of takeovers involving AT&T and many of the country’s other major corporations.

Looking forward, the appointment of Republican former U.S. Federal Trade Commission member Joshua Wright to lead Donald Trump’s transition team that is focused on the Federal Trade Commission may signal even more mergers in the years ahead. Earlier this month Wright expressed his view that

Economists have long rejected the “antitrust by the numbers” approach. Indeed, the quiet consensus among antitrust economists in academia and within the two antitrust agencies is that mergers between competitors do not often lead to market power but do often generate significant benefits for consumers — lower prices and higher quality. Sometimes mergers harm consumers, but those instances are relatively rare.

Because the economic case for a drastic change in merger policy is so weak, the new critics argue more antitrust enforcement is good for political reasons. Big companies have more political power, they say, so more antitrust can reduce this power disparity. Big companies can pay lower wages, so we should allow fewer big firms to merge to protect the working man. And big firms make more money, so using antitrust to prevent firms from becoming big will reduce income inequality too. Whatever the merits of these various policy goals, antitrust is an exceptionally poor tool to use to achieve them. Instead of allowing consumers to decide companies’ fates, courts and regulators decided them based on squishy assessments of impossible things to measure, like accumulated political power. The result was that antitrust became a tool to prevent firms from engaging in behavior that benefited consumers in the marketplace.

And, no doubt, there will be plenty of mainstream economists who will be willing, for large payouts, to present the models that justify a new wave of corporate mergers and acquisitions in the years ahead.