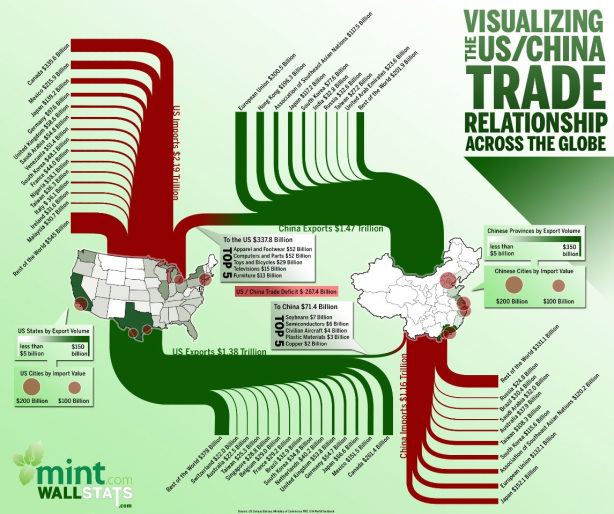

From David Ruccio There are two sides to the recent China Shock literature created by David Autor and David Dorn and surveyed by Noah Smith. On one hand, Autor and Dorn (with a variety of coauthors) have challenged the free-trade nostrums of mainstream economists and economic elites—that everyone benefits from free international trade. Using China as an example, they show that increased trade hurt American workers, increased political polarization, and decreased U.S. corporate innovation. The case for free international trade now lies in tatters, which of course played an important role in the Brexit vote as well as in the U.S. presidential campaign. On the other hand, invoking the China Shock has tended to reinforce economic nationalism—treating China as an unitary entity, a country has shaken up world trade patterns, and disregarding the conditions and consequences of increased trade with other countries, including the United States. source Why has there been an increasing U.S. trade deficit with China in recent decades? As James Chan explained, in response to an August 2016 article in the Wall Street Journal, Our so-called China problem isn’t really with the Chinese but rather our own multinational companies. As I see it, U.S.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

There are two sides to the recent China Shock literature created by David Autor and David Dorn and surveyed by Noah Smith.

On one hand, Autor and Dorn (with a variety of coauthors) have challenged the free-trade nostrums of mainstream economists and economic elites—that everyone benefits from free international trade. Using China as an example, they show that increased trade hurt American workers, increased political polarization, and decreased U.S. corporate innovation.

The case for free international trade now lies in tatters, which of course played an important role in the Brexit vote as well as in the U.S. presidential campaign.

On the other hand, invoking the China Shock has tended to reinforce economic nationalism—treating China as an unitary entity, a country has shaken up world trade patterns, and disregarding the conditions and consequences of increased trade with other countries, including the United States.

Why has there been an increasing U.S. trade deficit with China in recent decades? As James Chan explained, in response to an August 2016 article in the Wall Street Journal,

Our so-called China problem isn’t really with the Chinese but rather our own multinational companies.

As I see it, U.S. corporations have made a variety of decisions—to subcontract the production of parts and components with enterprises in China (which are then used in products that are later imported into the United States), to purchase goods produced in China to sell in the United States (which then show up in U.S. stores), to outsource their own production of goods (to sell in China and to export to the United States), and so on. The consequences of those corporate decisions (and not just with respect to China) include disrupting jobs and communities in the United States (through outsourcing and import competition) and decreasing innovation (since existing technologies can be used both to produce goods in China and sell in the expanding Chinese consumer market), thereby increasing political polarization in the United States.

The flip side of the story is the accumulation of capital in China. Until the development of the conditions for the development of capitalism existed in China, none of those corporate decisions were possible—not by U.S. corporations nor by multinational enterprises from other countries, all of whom were eager to take advantage of the growth of capitalism in China. Which of course they then contributed to, thus spurring the widening and deepening of capital accumulation within China.

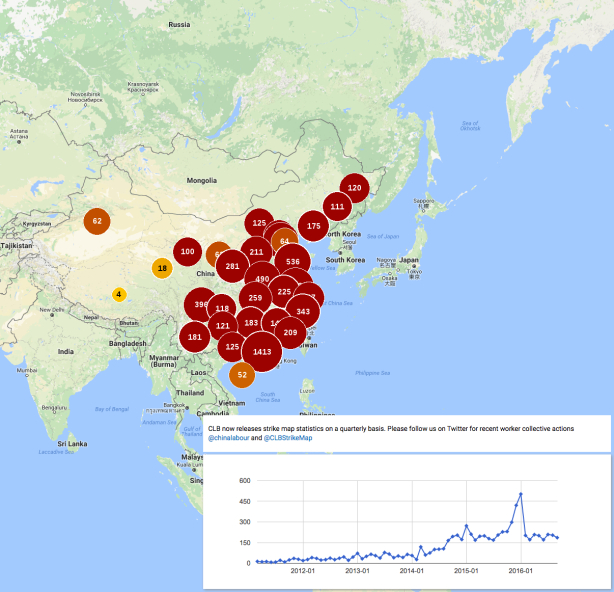

It should come as no surprise, then, that there’s been an upsurge of strike activity by workers in the fast-growing centers of manufacturing and construction within China—especially in the provinces of Guandong, Shandong, Henan, Sichuan, and Hebei.

According to Hudson Lockett, China this year

saw a total of 1,456 strikes and protests as of end-June, up 19 per cent from the first half of 2015

The problem with the China Shock literature, which has served to challenge the celebration of free-trade by mainstream economists and economic elites in the West, is that it hides from view both the decisions by U.S. corporations that have increased the U.S. trade deficit with China (with the attendant negative consequences “at home”) and the activity by Chinese workers to contest the conditions under which they have been forced to have the freedom to labor (which we can expect to continue for years to come).

It’s our responsibility to keep those decisions and events in view. Otherwise, we risk the economic and political equivalent of the China Syndrome.