From David Ruccio According to a new report from the Pew Research Center, in 2014, for the first time in more than 130 years, adults aged 18 to 34 were more likely to be living in their parents’ home than they were to be living with a spouse or partner in their own household or in any other living arrangement. Dating back to 1880, the most common living arrangement among young adults has been living with a romantic partner, whether a spouse or a significant other. This type of arrangement peaked around 1960, when 62% of the nation’s 18- to 34-year-olds were living with a spouse or partner in their own household, and only one-in-five were living with their parents. By 2014, 31.6% of young adults were living with a spouse or partner in their own household, below the share living in the home of their parent(s) (32.1%). Some 14% of young adults were heading up a household in which they lived alone, were a single parent or lived with one or more roommates. The remaining 22% lived in the home of another family member (such as a grandparent, in-law or sibling), a non-relative, or in group quarters (college dormitories fall into this category). So, what’s going on? .

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

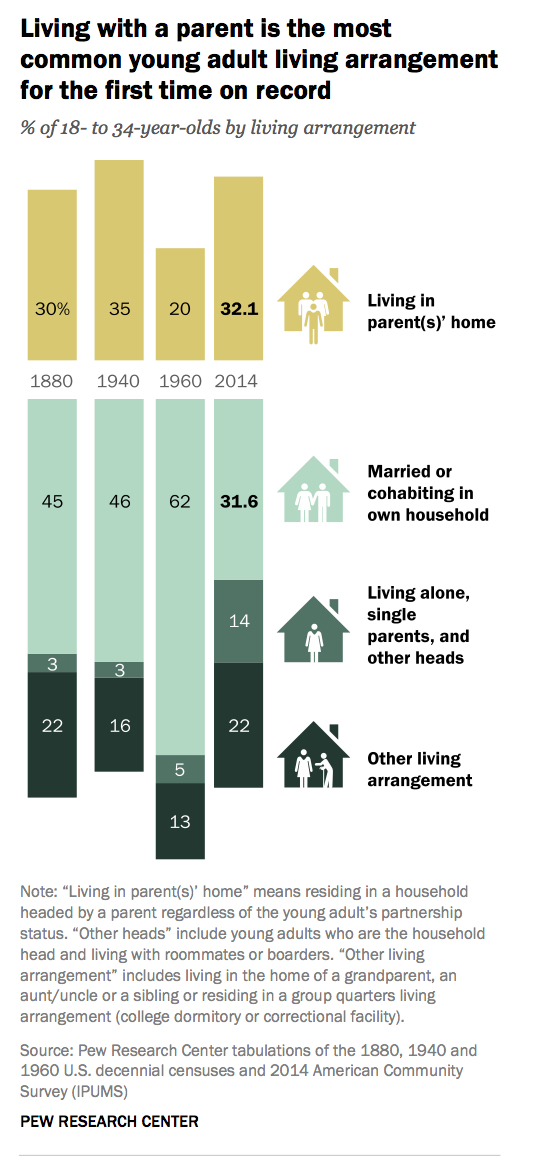

According to a new report from the Pew Research Center, in 2014, for the first time in more than 130 years, adults aged 18 to 34 were more likely to be living in their parents’ home than they were to be living with a spouse or partner in their own household or in any other living arrangement.

Dating back to 1880, the most common living arrangement among young adults has been living with a romantic partner, whether a spouse or a significant other. This type of arrangement peaked around 1960, when 62% of the nation’s 18- to 34-year-olds were living with a spouse or partner in their own household, and only one-in-five were living with their parents.

By 2014, 31.6% of young adults were living with a spouse or partner in their own household, below the share living in the home of their parent(s) (32.1%). Some 14% of young adults were heading up a household in which they lived alone, were a single parent or lived with one or more roommates. The remaining 22% lived in the home of another family member (such as a grandparent, in-law or sibling), a non-relative, or in group quarters (college dormitories fall into this category).

So, what’s going on?

.

On one hand, a single kind of household arrangement (married or cohabitating in one’s own household), which peaked in 1960, has given way to a variety of arrangements (including living with parents, single parenting, living with family members other than parents, and living on one’s own or with a non-related group). Clearly, for young adults, the Leave-It-to-Beaver household has been displaced by many different alternatives.

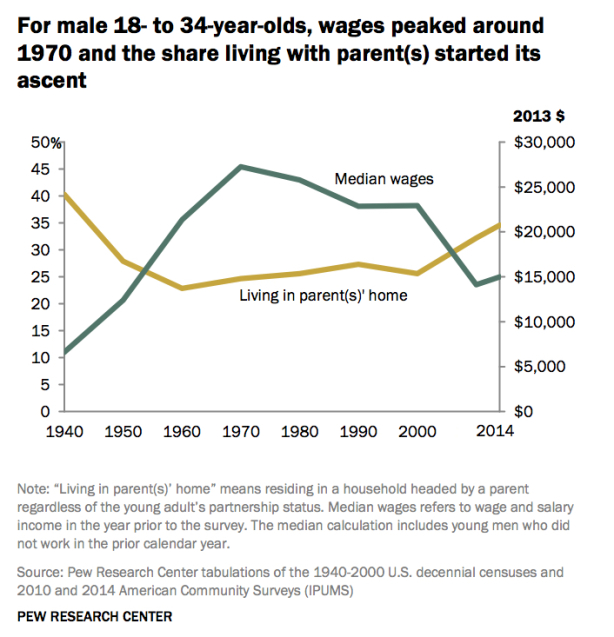

Except, of course, many young adults are staying or moving back in with their parents, in traditional households that are presumably being transformed by their presence. And, as the report makes clear, “trends in both employment status and wages have likely contributed to the growing share of young adults who are living in the home of their parent(s), and this is especially true of young men.”

Young men’s wages peaked around 1970 and they’ve been declining ever since—first gradually and then, after 2000, precipitously. And, as their earnings declined, the share of young men living in the home of their parent(s) has risen.*

More recently, the absence of an effective social safety net in the midst of the Second Great Depression has meant that many young workers have been forced to avail themselves of the private safety net of their parents’ households.**

That, of course, is only a short-term solution. Longer term, it means that, as a society, we have to both open up the discourse of the family and create the conditions whereby young adults can imagine and create new, more vibrant forms of householding for themselves.

And not just move back in with their parents.

*According to the report, “Economic factors seem to explain less of why young adult women are increasingly likely to live at home. Generally, young women have had growing success in the paid labor market since 1960 and hence might increasingly be expected to be able to afford to live independently of their parents. For women, delayed marriage—which is related, in part, to labor market outcomes for men—may explain more of the increase in their living in the family home.”

**As for the folks at FiveThirtyEight, they can’t seem to decide if it’s the economy or not that explains young adults moving back in with their parents. First, it’s not the economy (but, instead, “long-run shifts in demographics and behavior”); then, it is the economy (“The strong job market of the early 2000s overcame the demographic forces, allowing young singles to afford their own apartments and essentially suppressing the living-with-mom trend until the Great Recession hit.”). So, for the folks who are so confident with their “value-free” numbers (in, e.g., writing story after story bashing Bernie Sanders), which is it?