From David Ruccio Everyone (from President Obama to venture capitalist Alan Patricof) agrees the carried tax loophole—which allows investment fund managers to treat much of their income as capital gains (taxed at a top rate of 23.8 percent) rather than as income (for which the top rate is 39.6 percent)—should be closed. But, as Michael Hiltzik reminds us, it’s a tax break the super rich are willing to give up in order to keep the loophole they really value: the capital gains tax break. Here are the numbers: The carried interest loophole produces an aggregate tax break of billion to billion a year, depending on how you reckon. That’s not peanuts, especially at the high end of the estimated range, but the advantage accrues mostly to real estate and private equity fund managers. The preference rate for capital gains and dividends, however, costs the treasury an estimated 0 billion a year — anywhere from six to 60 times as much. That’s a commensurate gain for those earning a significant chunk of their income from capital gains, and they’re overwhelmingly members of the 1%. . . In fact, in 2015, capital gains made up 40 percent of the incomes of the top 0.1 percent, and even more—53 percent—for those in the top 0.1 percent.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Everyone (from President Obama to venture capitalist Alan Patricof) agrees the carried tax loophole—which allows investment fund managers to treat much of their income as capital gains (taxed at a top rate of 23.8 percent) rather than as income (for which the top rate is 39.6 percent)—should be closed.

But, as Michael Hiltzik reminds us, it’s a tax break the super rich are willing to give up in order to keep the loophole they really value: the capital gains tax break.

Here are the numbers: The carried interest loophole produces an aggregate tax break of $2 billion to $20 billion a year, depending on how you reckon. That’s not peanuts, especially at the high end of the estimated range, but the advantage accrues mostly to real estate and private equity fund managers.

The preference rate for capital gains and dividends, however, costs the treasury an estimated $120 billion a year — anywhere from six to 60 times as much. That’s a commensurate gain for those earning a significant chunk of their income from capital gains, and they’re overwhelmingly members of the 1%. . .

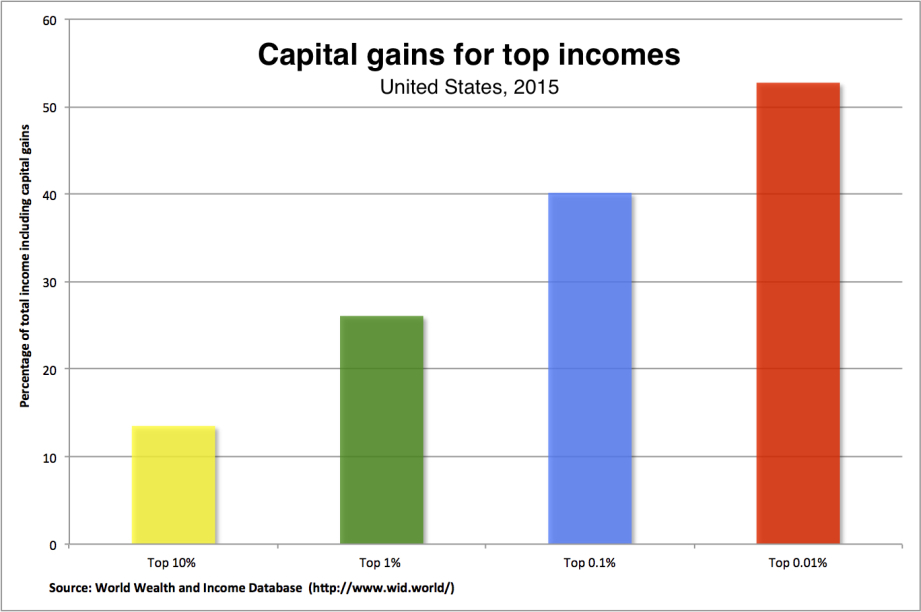

In fact, in 2015, capital gains made up 40 percent of the incomes of the top 0.1 percent, and even more—53 percent—for those in the top 0.1 percent.

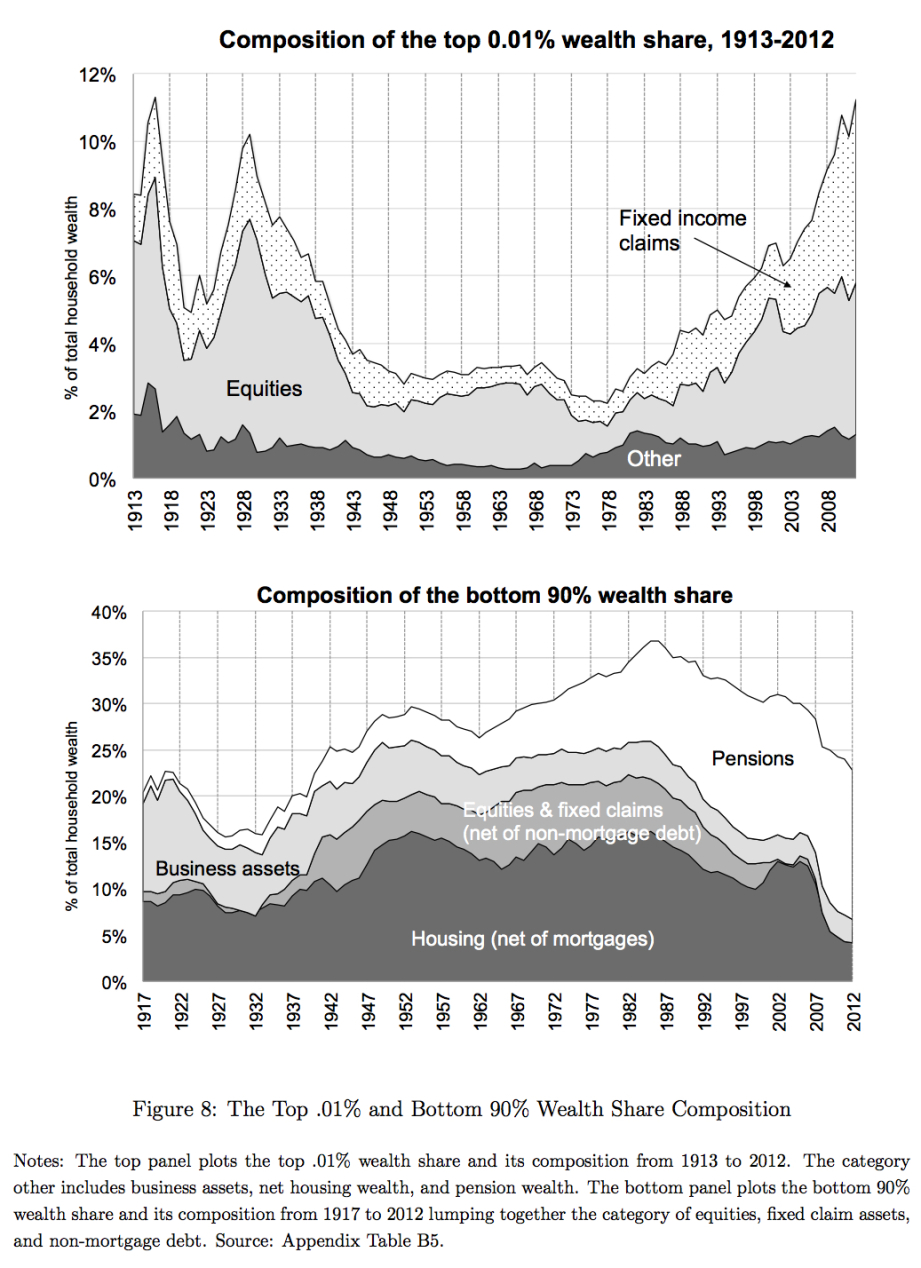

That’s because the ownership of wealth, especially corporate equity, is so unequally distributed in the United States—and it has only gotten more unequal over the course of the past four decades. As Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman have shown, the average net wealth per U.S. family ($350,000 in 2012) masks considerable heterogeneity. Thus, for the bottom 90 percent, average wealth was $84 thousand, which corresponded to a share of total wealth of 22.8 percent; while for the top .01 percent (a total of 16 thousand families), average wealth was $371 million, for a total wealth share of 11.2 percent.

In fact, as the authors explain,

At the very top end of the distribution, wealth is now as unequally distributed as in the 1920s. In 2012, the top 0.01% wealth share (fortunes of more than $110 million dollars belonging to the richest 16,000 families) is 11.2%, as much as in 1916 and more than in 1929. Further down the ladder, top wealth shares, although rising fast, are still below their Roaring Twenties peaks. The top 0.1% share is still about 2.8 points lower in 2012 than in 1929 (22.0% vs. 24.8%), and the top 1% share about 9.6 points lower (41.8% vs. 50.6%). Wealth is getting more concentrated in the United States, but this phenomenon largely owes to the spectacular dynamics of fortunes of dozens and hundreds of million dollars, and much less to the growth in fortunes of a few million dollars. Inequality within rich families is increasing.

Moreover,

The long run dynamics of the very top group we consider—the top 0.01%—are particularly striking. The losses experienced by the wealthiest families from the late 1920s to the late 1970s were so large that in 1980, the average real wealth of top 0.01% families ($44 million in constant 2010 prices) was half its 1929 value ($87 million). It took almost 60 years for the average real wealth of the top 0.01% to recover its 1929 value—which it did in 1988. . .Financial regulation sharply limited the role of finance and the ability to concentrate wealth as in the Gilded age model of the financier-industrialist. Part of these policies were reversed in the 1980s, and we find that top 0.01% average wealth has been growing at a real rate of 7.8% per year since 1988. In 1978, top 0.01% wealth holders were 220 times richer than the average family. In 2012, they are 1,120 times richer.

Now that their fortunes have recovered—and continued to grow, based on corporate equities (in addition to fixed-income claims)—those at the very top of the wealth distribution in the United States aren’t interested in letting it go. Therefore, they’re willing to give up the small potatoes of the carried interest tax loophole in order to safeguard their much more important and lucrative capital gains tax break.

So, as Hiltzik explains,

keep this in mind the next time wealthy taxpayers ask to be patted on the head for advocating an end to the carried interest loophole: The real tax break is the one they’re not talking about.