From David Ruccio Eduardo Porter is right: the “long, painful slog out of the Great Recession” hasn’t been accompanied by any kind of shared prosperity. As the chart above reveals, the share of income going to the bottom 90 percent of U.S. households has actually fallen since 2007 (from 50.3 percent to 49.5 percent)—and, in recent years, remains far below what it was (67.4 percent) in 1970. In other words, the so-called recovery looks a lot like the unequalizing dynamic of the U.S. economy in the years and decades leading up to the Great Recession. Those who work for a living have been getting less and less, while those at the top have managed to capture and keep the growing surplus. We’re not just talking about the white working-class. Wages “for all groups of workers (not just those without a bachelor’s degree), regardless of race, ethnicity, or gender”, have (since 1979) have lagged the growth in economy-wide productivity. And that’s just in terms of income. As Porter explains, by many other metrics, Americans’ well-being remains pretty low. Whether it is life expectancy or infant mortality, incarceration or educational attainment, countless statistics offer a fairly dark picture of the American experience. It is a picture of prosperity that consistently leaves large numbers of Americans behind.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

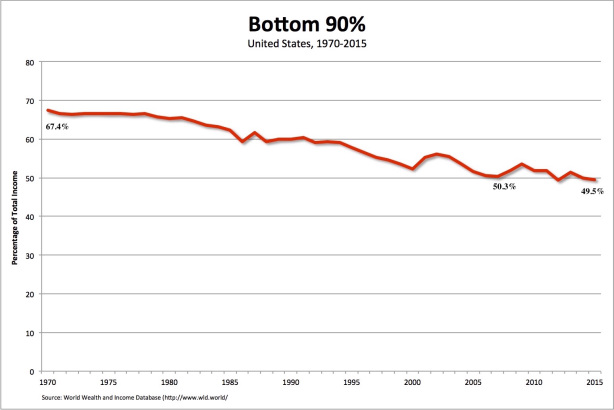

Eduardo Porter is right: the “long, painful slog out of the Great Recession” hasn’t been accompanied by any kind of shared prosperity.

As the chart above reveals, the share of income going to the bottom 90 percent of U.S. households has actually fallen since 2007 (from 50.3 percent to 49.5 percent)—and, in recent years, remains far below what it was (67.4 percent) in 1970.

In other words, the so-called recovery looks a lot like the unequalizing dynamic of the U.S. economy in the years and decades leading up to the Great Recession. Those who work for a living have been getting less and less, while those at the top have managed to capture and keep the growing surplus.

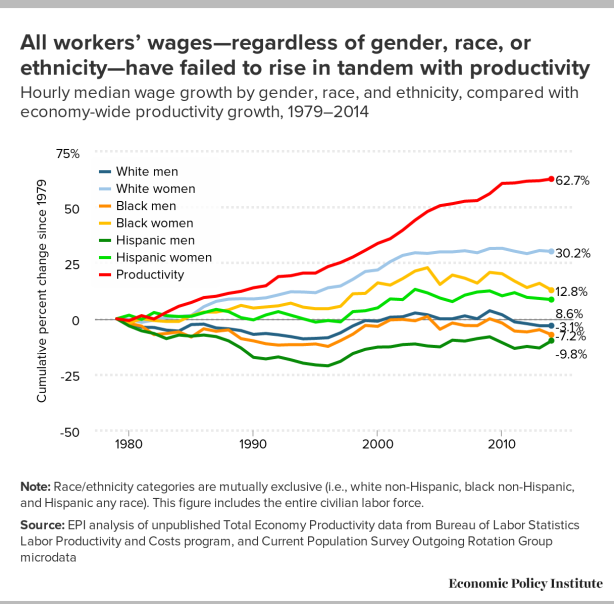

We’re not just talking about the white working-class. Wages “for all groups of workers (not just those without a bachelor’s degree), regardless of race, ethnicity, or gender”, have (since 1979) have lagged the growth in economy-wide productivity.

And that’s just in terms of income. As Porter explains,

by many other metrics, Americans’ well-being remains pretty low. Whether it is life expectancy or infant mortality, incarceration or educational attainment, countless statistics offer a fairly dark picture of the American experience. It is a picture of prosperity that consistently leaves large numbers of Americans behind.

The United States suffers the highest obesity rate among the 35 industrialized countries that make up the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. In terms of life expectancy at birth, it ranks 10th from the bottom. America’s infant mortality rate has dropped by half since 1980. Still, today Turkey and Mexico are the only countries in the O.E.C.D. to report a higher share of dead babies. Infant mortality fell faster in almost every other industrialized country.

Mainstream economists, politicians, and pundits may prefer to focus on the first part of Charles Dickens’s famous opening sentence. But that’s only true for the tiny group at the top. For everyone else, it really is—and has been for decades—”the worst of times.”