There has recently been a fuzz about the 26% Irish 2015 GDP growth rate. For more timely discussion of this phenomenon,look here and here on this blog (though I have to admit that I was flabbergasted too by the upward revision of Irish growth from about 9% to about 26%: beyond imagination). What to make of this? The Irish Central Statistical Office is not happy about it, too, and states: “the CSO intends to convene a high-level cross-sector consultative group” to address this situation. Two points for this discussion: There is no fundamental problem with the nominal accounts though there may be a practical one. The only other country which, at this moment, has labour income as low as Ireland is financial paradise Luxembourg… developments were beyond imagination but not beyond statistics. Which is of course due to high ‘property income’ flowing to company headquarters located in Luxembourg. Do we want to measure this? Or do we want a GDP variable which basically estimates the result of work, instead of the result of (legal!) financial shenanigans? The new national accounts (the system of national accounting has recently been revised, to stay up to date) stresses ownership of capital, which means that it looks less at where flows of goods are located (say, the Belgian port of Antwerp) but at who controls and owns these flows (say, a Lithuanian import-export company).

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

There has recently been a fuzz about the 26% Irish 2015 GDP growth rate. For more timely discussion of this phenomenon,look here and here on this blog (though I have to admit that I was flabbergasted too by the upward revision of Irish growth from about 9% to about 26%: beyond imagination). What to make of this? The Irish Central Statistical Office is not happy about it, too, and states: “the CSO intends to convene a high-level cross-sector consultative group” to address this situation. Two points for this discussion:

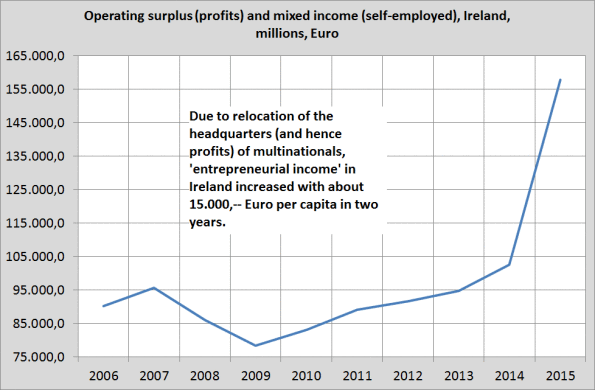

- There is no fundamental problem with the nominal accounts though there may be a practical one. The only other country which, at this moment, has labour income as low as Ireland is financial paradise Luxembourg… developments were beyond imagination but not beyond statistics. Which is of course due to high ‘property income’ flowing to company headquarters located in Luxembourg. Do we want to measure this? Or do we want a GDP variable which basically estimates the result of work, instead of the result of (legal!) financial shenanigans? The new national accounts (the system of national accounting has recently been revised, to stay up to date) stresses ownership of capital, which means that it looks less at where flows of goods are located (say, the Belgian port of Antwerp) but at who controls and owns these flows (say, a Lithuanian import-export company). The same for profits. As some large USA companies have relocated their headquarters (or at least the legal entities which are called headquarters) to Ireland this means that ‘Irish’ profits soared with 60 billion in two years. However – the basic break downs of GDP like household income, consumption and the like are not affected. Should we look at more metrics than just GDP?

- There are however large and fundamental problems with everything which is expressed in ‘real’ terms on the macro level (i.e. everything deflated with a price level) as profits (which are such a large part of Irish GDP) do not have a price level. Aggregate productivity is also rendered meaningless. Which means, long story short, that we will have to treat national accounts on the macro level more as a system of nominal variables while aspects like the purchasing power of nominal income (no, not the purchasing power of money!) or unit labour costs will have to be treated as sectoral variables. And not as macro variables.