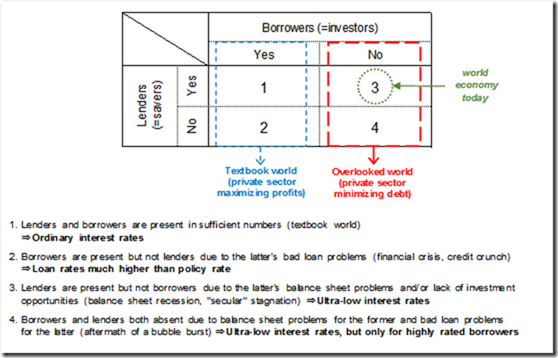

Four possible states of borrowers and lenders The discussion above suggests an economy is always in one of four possible states depending on the presence or absence of lenders (savers) and borrowers (investors). They are as follows: (1) both lenders and borrowers are present in sufficient numbers, (2) there are borrowers but not enough lenders even at high interest rates, (3) there are lenders but not enough borrowers even at low interest rates, and (4) both lenders and borrowers are absent. These four states are illustrated in Exhibit 2. Of the four, only Cases 1 and 2 are discussed in traditional economics, which implicitly assumes there are always borrowers as long as real interest rates can be brought low enough. And of these two, only Case 1 requires a minimum of policy intervention – such as slight adjustments to interest rates – to keep the economy going. The causes of Case 2 (insufficient lenders) may be found in both financial and non-financial factors. Non-financial factors might include a culture that does not encourage saving or a country that is simply too poor and underdeveloped to save. A restrictive monetary policy may also qualify as a non-financial factor that weighs on savers’ ability to lend. (If the paradox of thrift leaves a country too poor to save, this would be classified as Case 3 or 4 because it is actually due to a lack of borrowers.

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Four possible states of borrowers and lenders

The discussion above suggests an economy is always in one of four possible states depending on the presence or absence of lenders (savers) and borrowers (investors). They are as follows: (1) both lenders and borrowers are present in sufficient numbers, (2) there are borrowers but not enough lenders even at high interest rates, (3) there are lenders but not enough borrowers even at low interest rates, and (4) both lenders and borrowers are absent. These four states are illustrated in Exhibit 2.

Of the four, only Cases 1 and 2 are discussed in traditional economics, which implicitly assumes there are always borrowers as long as real interest rates can be brought low enough. And of these two, only Case 1 requires a minimum of policy intervention – such as slight adjustments to interest rates – to keep the economy going.

The causes of Case 2 (insufficient lenders) may be found in both financial and non-financial factors. Non-financial factors might include a culture that does not encourage saving or a country that is simply too poor and underdeveloped to save. A restrictive monetary policy may also qualify as a non-financial factor that weighs on savers’ ability to lend. (If the paradox of thrift leaves a country too poor to save, this would be classified as Case 3 or 4 because it is actually due to a lack of borrowers.)

Financial factors weighing on lenders might include an excess of many non-performing loans (NPLs), which depresses banks’ capital ratios and prevents them from lending. This is what is typically called a credit crunch.

When many banks encounter NPL problems at the same time, mutual distrust among lenders may lead to a dysfunctional interbank market, a state of affairs typically known as a financial crisis. Over-regulation of financial institutions by the authorities can lead to a credit crunch as well. An underdeveloped financial system may also be a factor.

Cultural norms discouraging savings, as well as income (and productivity) levels that are simply too low for people to save, are developmental phenomena typically found in pre-industrialized societies. These issues can take many years to address.

Exhibit 2. Borrowers and lenders: four possible states

Non-developmental causes of a shortage of lenders, however, all have well-known remedies in the literature. For example, the government can inject capital into the banks to restore their ability to lend, or it can relax regulations preventing financial institutions from performing their role as financial intermediaries. In the case of a dysfunctional interbank market, the central bank can act as lender of last resort to ensure the clearing system continues to operate. It can also relax monetary policy.

The conventional emphasis on monetary policy and concerns over the crowding-out effect of fiscal policy are justified in Cases 1 and 2, where there are borrowers but (for a variety of reasons in Case 2) not enough lenders.

A shortage of borrowers and the other half of macroeconomics

The problem is with Cases 3 and 4, where the bottleneck is a lack of borrowers. This is the other half of macroeconomics that has been overlooked by traditional economists.

As noted above, there are two main reasons for an absence of private-sector borrowers. The first is that they cannot find attractive investment opportunities that will pay for themselves, and the second is that their financial health has deteriorated to the point where they are unable to borrow until they repair their balance sheets. An example of the first case would be the world that existed prior to the industrial revolution, while examples of the second case can be found following the collapse of debt-financed asset price bubbles.

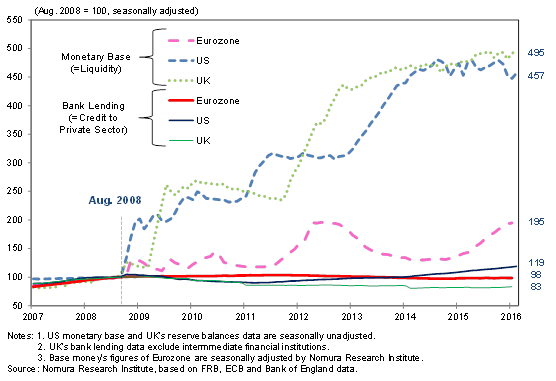

Exhibit 3. Massive liquidity supply and record low interest rates after 2008 failed to increase credit to private sector

Borrowers who have absented themselves because their balance sheets are underwater will not return until their negative equity problems are resolved. Depending on the size of the bubble, this can take many years even under the best of circumstances. Furthermore, the economy will enter the $1,000–$900–$810–$730 deflationary scenario mentioned earlier if the private sector as a whole is saving money (or paying down debt) in spite of zero interest rates.

When borrowers disappear, there is very little that monetary policy, the favorite of traditional economists, can do to prop up the real economy. Exhibit 3 shows that the close relationship between central-bank-supplied liquidity, known as the monetary base, and growth in private-sector credit seen prior to 2008 broke down completely after the bubble burst and the private sector began minimizing debt. This exhibit makes it clear that the monetary base and credit to the private sector were closely correlated prior to 2008, just as economics textbooks teach. In other words, the private sector was utilizing all the funds supplied by the central bank, and economies were in Case 1 of Exhibit 2.

But after the bubble burst, forcing the private sector to repair its balance sheet by minimizing debt, no amount of central bank accommodation could increase borrowings by the private sector. The US Federal Reserve, for example, expanded the monetary base by 357 percent from the time Lehman went under. In an ordinary (i.e., textbook) world, this should have led to similar increases in the money supply and credit, driving corresponding increases in inflation.

Instead, credit to the private sector increased only 19 percent over seven and a half years. A central bank can always add liquidity to the banking system by purchasing assets from financial institutions. But for that liquidity to enter the real economy, banks must lend out those funds: they cannot give them away because the funds are ultimately owned by depositors. A mere 19 percent increase in lending means new money entering the real economy from the financial sector has grown only 19 percent since 2008. Similar patterns have been observed in the Eurozone and the UK. This explains why inflation and growth rates in the advanced economies have all failed to respond to zero interest rates or astronomical injections of central bank liquidity since 2008.