From Michael Joffe In 1978, not long after the death of Mao Zedong, economic reforms began to be implemented. The main changes were: (i) rural households were now allowed to keep their own surpluses (the “household-responsibility system”); (ii) Township and Village Enterprises were allowed to operate in a manner similar to capitalist firms; (iii) Special Economic Zones such as Shenzhen were set up, based on foreign capital and the export market; and (iv) State-Owned Enterprises were increasingly required to operate according to market logic to improve their economic efficiency (Lin et al., 2008). The first two of these, peasant agriculture and Township and Village Enterprises, did not need large quantities of investment, as they were both low-cost activities; in very many instances

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Michael Joffe

In 1978, not long after the death of Mao Zedong, economic reforms began to be implemented. The main changes were: (i) rural households were now allowed to keep their own surpluses (the “household-responsibility system”); (ii) Township and Village Enterprises were allowed to operate in a manner similar to capitalist firms; (iii) Special Economic Zones such as Shenzhen were set up, based on foreign capital and the export market; and (iv) State-Owned Enterprises were increasingly required to operate according to market logic to improve their economic efficiency (Lin et al., 2008). The first two of these, peasant agriculture and Township and Village Enterprises, did not need large quantities of investment, as they were both low-cost activities; in very many instances they gradually expanded by ploughing their profits back into the business. The capital for investment in State-Owned Enterprises continued to be the responsibility of government, in continuity with the pre-reform era. In contrast, the Special Economic Zones did rely on new sources of funding, largely foreign direct investment – which had the additional advantage of bringing technology and knowhow with it – but also some portfolio investment. Much of this foreign capital was from neighbors that had already developed substantial modern industry, and that also had close cultural links, especially Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Replacement of Soviet-style centralized planning by organizations that operated more like capitalist firms had a dramatic impact on the economy. In particular, the manufacturing sector developed on the basis of very low unit costs – low wages relative to the productivity level. This, together with an undervalued currency, enabled Chinese products to be marketed extremely cheaply, which became known as the “China price”. The result was that Chinese manufactures conquered the world.

Within China, the large and ever-growing volume of exports led not only to unprecedented levels of sustained economic growth, and rising living standards for an increasing proportion of the population, but also to soaring quantities of capital. This largely consisted of corporate profits from export sales, predominantly in foreign hard currency. In addition, household saving rates were extremely high, due to increasing wages together with an important precautionary element because of low social security provision, plus very likely a strong cultural element as well. These household savings were channeled by state banks to State-Owned Enterprises, allowing massive capital investments to be made, albeit not always in the most efficient manner.

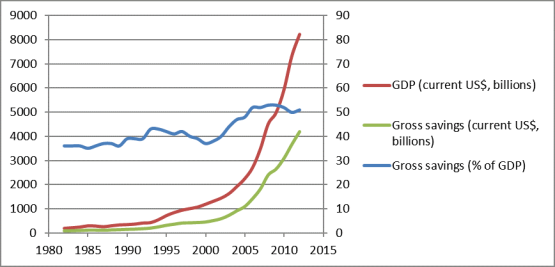

The saving rate, as a percentage of GDP, fluctuated between 35 and 43 percent – already high by international standards (especially if one excludes oil exporters) – until the early 2000s, when it rose to 50 percent or above (figure 3). The well-known near-exponential Chinese GDP growth was thus accompanied by equally strong growth in gross savings, with an even steeper increase during 2002-2006 (figure 3). It is plausible that the rise in percent savings in this latter period was at least partly due to the ever-increasing prosperity of industry and also of its employees, whose consumption level did not keep up with their increase in earnings.

Figure 3 Growth and savings in China, 1982-2012

Source: World Bank http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/

Much of this capital was ploughed back into domestic investment in industry and infrastructure. But not all of it – copious quantities flowed overseas. The destinations were diverse: some was used to purchase bonds, e.g. US Treasury bonds. Some went into buying existing infrastructure, or building new infrastructure (especially in Africa). Some went into productive investment in western industry, giving access to technology and brands. The Chinese current account rose from its previously positive but relatively moderate level close to the range 20-40 billion US dollars annually in 1998-2003 to a peak of 420 billion in 2008, before falling back to approximately 150-250 billion since then (State Administration of Foreign Exchange, China; World Bank).

One factor that may have contributed to the export of capital from China was a precautionary motive, following the experience of many East Asian countries during the crisis of the late 1990s. However, the figures do not support this as an important factor, because the main rise in capital exports did not begin until 2004, several years after the East Asian Crisis.

In summary, international capital flows involving China showed a persistently positive current account starting in the late 1990s. In other words, capital was exported from this relatively poor country, e.g. in terms of GDP per capita, mainly to rich countries such as the USA. There is no puzzle about this, because the quantity of corporate profits and of domestic savings has been so enormous that it is unsurprising that some of it would flow abroad – especially as much of it was in hard currency, derived from exports.

from

Michael Joffe, “Why does capital flow from poor to rich countries? – The real puzzle”, real-world economics review, issue no. 81, 30 September 2017, pp. 42-62, , http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue81/Joffe81.pdf