From David Ruccio The capitalist machine is broken—and no one seems to know how to fix it. The machine I’m referring to is the one whereby the “capitalist” (i.e., the boards of directors of large corporations) converts the “surplus” (i.e., corporate profits) into additional “capital” (i.e., nonresidential fixed investment)—thereby preserving the pact with the devil: the capitalists are the ones who get and decide on the distribution of the surplus, and then they’re supposed to use the surplus for investment, thereby creating economic growth and well-paying jobs. The presumption of mainstream economists and business journalists (as well as political and economic elites) is that the capitalist machine is the only possible one, and that it will work. Except it’s not: corporate profits have been growing (the red line in the chart above) but investment has been falling (the blue line in the chart), both in the short run and in the long run. Between 2008 and 2015, corporate profits have soared (as a share of gross domestic income, from 3.9 to 6.3 percent) but investment has decreased (as a share of gross domestic product, from 13.5 to 12.4 percent). Starting from 1980, the differences are even more stark: corporate profits were lower (3.6 percent) and investment was much higher (14.5 percent).

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

The capitalist machine is broken—and no one seems to know how to fix it.

The machine I’m referring to is the one whereby the “capitalist” (i.e., the boards of directors of large corporations) converts the “surplus” (i.e., corporate profits) into additional “capital” (i.e., nonresidential fixed investment)—thereby preserving the pact with the devil: the capitalists are the ones who get and decide on the distribution of the surplus, and then they’re supposed to use the surplus for investment, thereby creating economic growth and well-paying jobs.

The presumption of mainstream economists and business journalists (as well as political and economic elites) is that the capitalist machine is the only possible one, and that it will work.

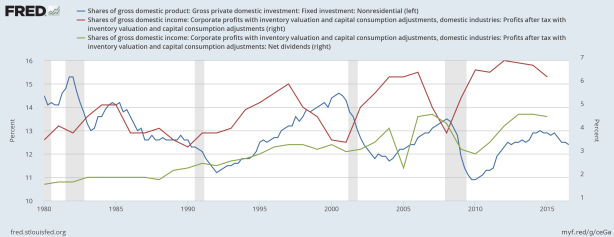

Except it’s not: corporate profits have been growing (the red line in the chart above) but investment has been falling (the blue line in the chart), both in the short run and in the long run. Between 2008 and 2015, corporate profits have soared (as a share of gross domestic income, from 3.9 to 6.3 percent) but investment has decreased (as a share of gross domestic product, from 13.5 to 12.4 percent). Starting from 1980, the differences are even more stark: corporate profits were lower (3.6 percent) and investment was much higher (14.5 percent).

The fact that the machine is not working—and, as a result, growth is slowing down and job-creation is not creating the much-promised rise in workers’ wages—has created a bit of a panic among mainstream economists and business journalists.

Larry Summers, for example, finds himself reaching back to Alvin Hansen and announcing we’re in a period of “secular stagnation”:

Most observers expected the unusually deep recession to be followed by an unusually rapid recovery, with output and employment returning to trend levels relatively quickly. Yet even with the U.S. Federal Reserve’s aggressive monetary policies, the recovery (both in the United States and around the globe) has fallen significantly short of predictions and has been far weaker than its predecessors. Had the American economy performed as the Congressional Budget Office forecast in August 2009—after the stimulus had been passed and the recovery had started—U.S. GDP today would be about $1.3 trillion higher than it is.

Clearly, the current recovery has fallen far short of expectations. But then Summers seeks to calm fears—”secular stagnation does not reveal a profound or inherent flaw in capitalism”—and suggests an easy fix: all that has to happen is an increase in government-financed infrastructure spending to raise aggregate demand and induce more private investment spending.

As if rising profitability is not enough of an incentive for capitalists.

Noah Smith, for his part, is also worried the machine isn’t working, especially since, with low interest-rates, credit for investment projects is cheap and abundant—and yet corporate investment remains low by historical standards. Contra Summers, Smith suggests the real problem is “credit rationing,” that is, small companies have been shut out of the necessary funding for their investment projects. So, he would like to see policies that promote access to capital:

That would mean encouraging venture capital, small-business lending and more effort on the part of banks to seek out promising borrowers — basically, an effort to get more businesses inside the gated community of capital abundance.

Except, of course, banks have an abundance of money to lend—and venture capital has certainly not been sitting on the sidelines.

Profitability, in other words, is not the problem. What neither Summers nor Smith is willing to ask is what corporations are actually doing with their growing profits (not to mention cheap credit and equity funding via the stock market) if not investing them.

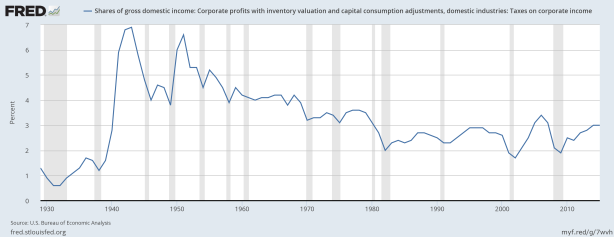

We know that corporations are not paying higher taxes to the government. As a share of gross domestic income, they’re lower than they were in 2006, and much lower than they were in the 1950s and 1960s. So, the corporate tax-cuts proposed by the incoming administration are not likely to induce more investment. Corporations will just be able to retain more of the profits they get from their workers.

But corporations are distributing their profits to other uses. Dividends to shareholders have increased dramatically (as a share of gross domestic income, the green line in the chart at the top of the post): from 1.7 percent in 1980 to 4.6 percent in 2015.

source (pdf)

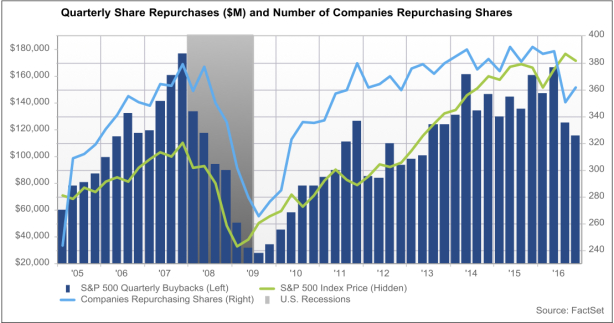

Corporations are also using their profits to repurchase their own shares (thereby boosting stock indices to record levels), to finance mergers and acquisitions (which increase concentration, but not investment, and often involve cutting jobs), to raise the income and wealth of CEOs (thus further raising incomes of the top 1 percent and increasing conspicuous consumption), and to hold cash (at home and, especially, in overseas tax havens).

And that’s the current dilemma: the machine is working but only for a tiny group at the top. For everyone else, it’s not—not by a long shot.

We can expect, then, a long line of mainstream economists and business journalists who, like Summers and Smith, will suggest one or another tool to tinker with the broken machine. What they won’t do is state plainly the current machine is beyond repair—and that we need a radically different one to get things going again.