From David Ruccio Now that President Trump has begun carrying out his campaign pledges to undo America’s trade ties, formally withdrawing the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and announcing he will start to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement, it’s time to analyze what this means. As it turns out, I’d already started to do this before the election, with a series of posts (e.g., here, here, here, and here) on Trump and the mounting criticism of the trade agreements the United States had signed (such as NAFTA) or was in the process of negotiating (the TPP). It’s clear Trump’s decisions—which he claims are a “Great thing for the American worker”—challenge the view of economic and political elites, as well as those of mainstream economists (such as Brad DeLong), in the United States and around the world that everyone benefits from free trade.* But, we now know, there has also been a growing counter-narrative, that not everyone has gained from growing international trade and trade agreements, which have generated unequal benefits and costs. What’s interesting about this alternative story, at least when it comes to NAFTA, is that critics on each side argue the other side is the one that has benefited: U.S.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Now that President Trump has begun carrying out his campaign pledges to undo America’s trade ties, formally withdrawing the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and announcing he will start to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement, it’s time to analyze what this means.

As it turns out, I’d already started to do this before the election, with a series of posts (e.g., here, here, here, and here) on Trump and the mounting criticism of the trade agreements the United States had signed (such as NAFTA) or was in the process of negotiating (the TPP).

It’s clear Trump’s decisions—which he claims are a “Great thing for the American worker”—challenge the view of economic and political elites, as well as those of mainstream economists (such as Brad DeLong), in the United States and around the world that everyone benefits from free trade.*

But, we now know, there has also been a growing counter-narrative, that not everyone has gained from growing international trade and trade agreements, which have generated unequal benefits and costs. What’s interesting about this alternative story, at least when it comes to NAFTA, is that critics on each side argue the other side is the one that has benefited: U.S. critics that Mexico has gained, and just the opposite in Mexico, that the United States has captured the lion’s share of the benefits from NAFTA.

Here’s the problem: workers on both sides of the border have lost out, and their losses are mostly not due to NAFTA.

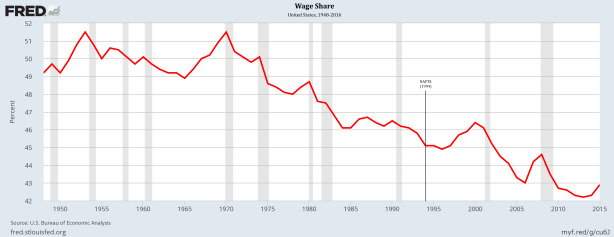

We know, for example, that the wage share of national income in the United States has in fact declined after NAFTA was implemented (in January 1994)—from 45.1 percent of gross domestic income to 42.9 percent. But we also have to recognize workers have been losing out since at least 1970, when the wage share stood at 51.5 percent.

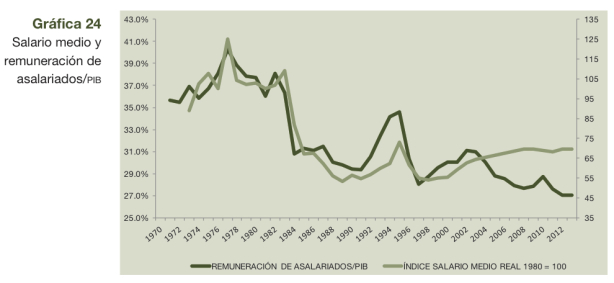

Much the same has been happening in Mexico, where (according to the research of Norma Samaniego Breach [pdf]), the wage share (the dark green line in the chart above) has been falling since 1978—and continued to fall after NAFTA was put into place. And, as Alice Krozera, Juan Carlos Moreno Brid, and Juan Cristóbal Rubio Badan have shown, economic and political elites in Mexico, much like their U.S. counterparts, have mostly ignored the problem of inequality and resisted efforts to raise the minimum wage and workers’ share of national income.

The fact is, while NAFTA did propel a large increase in trade between Mexico and the United States, it “did not cause the huge job losses feared by the critics or the large economic gains predicted by supporters” (according to a 2015 study commissioned by the Congressional Research Service [pdf]).

The bottom line is, eliminating or renegotiating NAFTA—including in the manner Trump is proposing—is not going to help the working-classes in either Mexico or the United States. It is merely a diversion from the real changes that need to be made, to which the political and economic elites as well as mainstream economists in both countries stand opposed.

*The only real debate within mainstream economics is between neoclassical economists who argue free trade generates the most efficient outcomes, within and between countries (regardless of whether countries run trade surpluses or deficits), and their critics (such as Jared Bernstein) who argue that trade deficits lead to a loss of jobs (e.g., in U.S. manufacturing), and thus require interventions of the sort Trump is proposing to change the pattern of international trade.