Weird: fifty years after Schumpeter and one hundred years after John Stuart Mill they did not mention ‘credit’. Let alone ‘private credit’. Mill’s idea that private credit creation often decisively contributes to bubbles, and bursts, is absent from the whole thing. The Schumpeterian idea that credit financed investments lead to economic growth (and monetary changes) is alien to their concept. Even the Irving Fisher idea that there are different kinds of money with different kinds of velocity is not really incorporated while the sectoral approach which is part and parcel of the main system of monetary statistics, the Flow of Funds, is not even mentioned. And Minsky’s clear warning that stocks of private debts are pivotal in engendering the deep depressions central to their analysis was

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Weird: fifty years after Schumpeter and one hundred years after John Stuart Mill they did not mention ‘credit’. Let alone ‘private credit’. Mill’s idea that private credit creation often decisively contributes to bubbles, and bursts, is absent from the whole thing. The Schumpeterian idea that credit financed investments lead to economic growth (and monetary changes) is alien to their concept. Even the Irving Fisher idea that there are different kinds of money with different kinds of velocity is not really incorporated while the sectoral approach which is part and parcel of the main system of monetary statistics, the Flow of Funds, is not even mentioned. And Minsky’s clear warning that stocks of private debts are pivotal in engendering the deep depressions central to their analysis was bluntly ignored.

Weird: fifty years after Schumpeter and one hundred years after John Stuart Mill they did not mention ‘credit’. Let alone ‘private credit’. Mill’s idea that private credit creation often decisively contributes to bubbles, and bursts, is absent from the whole thing. The Schumpeterian idea that credit financed investments lead to economic growth (and monetary changes) is alien to their concept. Even the Irving Fisher idea that there are different kinds of money with different kinds of velocity is not really incorporated while the sectoral approach which is part and parcel of the main system of monetary statistics, the Flow of Funds, is not even mentioned. And Minsky’s clear warning that stocks of private debts are pivotal in engendering the deep depressions central to their analysis was bluntly ignored.

I’m talking about the 1962 Milton Friedman/Anna Schwarz article ‘Money and Business Cycles’ (the Minsky comments can be found in the same document). According to Friedman and Schwarz, the government and only the government indirectly creates money mainly via central bank interest and QE like bank-liquidity policies. Period. Which makes the government, and only the government, responsible for these deep depressions. Period.

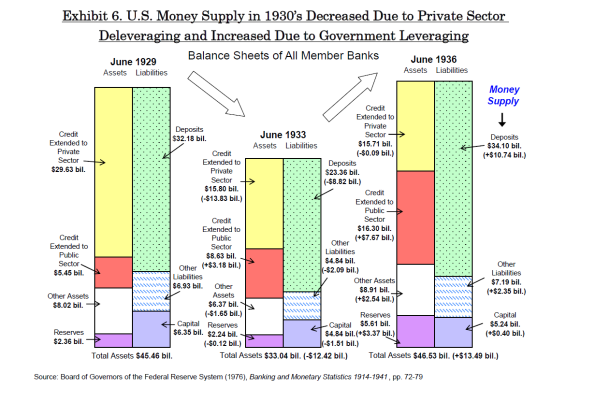

Remarkably, Friedman and Schwarz could have done better. In their work they focus attention on Crude and Clumsy Aggregates (CCA) of money. And they do pay attention to changes in the amount of money. But when push comes to play they pay zero attention to how the amount of money changes and which sectors of the economy cause these increases or decreases. While this information was available, at the time of writing. Morris Copeland (the 1957 president of the AEA) had already developed, together with the Fed, his Flow of Funds system which, in detailed fashion, showed where money came from and where it went. Before the end of the fifties, Central Banks all over the world (the USA, India, Germany…) had already started to construct Flow of Funds accounts. And, as the monthly press release of the ECB shows, it is totally possible to link the change in the amount of money to sectoral lending and borrowing. Aside: as this publication shows, Copeland and Friedman knew each other and in 1938 even commented on each others work on how to deflate series of nominal income and production, a problem still not satisfactorily solved. With their undue focus on money outside its social, political and economic context did a disservice to society and the economic community. Only one example: Richard Koo used Flow of Funds data (which, for this period, he had to assemble himself…) to show that during the Great Depression after 1933 the government, and not as implied by the analysis of Friedman and Schwarz the private sector, increased the amount of money by borrowing directly from banks – and increased prosperity and the flow of production and income by spending this money. More money as such did not increase nominal income – a government spending freshly printed private money did. Fast forward: instead of Friedman style QE policies, governments could have borrowed from banks and have spent the money on useful projects or healthcare. See Richard Werner on this. The work of Friedman and Schwarz should have included a chapter on the origin of money incorporating the ideas of Mill, Schumpeter, Fisher, Copeland and Minsky. But even in the 1975 sequel to the 1963 ‘A monetary history of the United States’ such information is lacking. Copeland is conspicuously absent from the references. The Flow of Funds is not mentioned in the index. And modern ideas that money and spending should not only be related to GDP ‘flow’ transactions but also to purchases of existing fixed assets (houses!) are also nowhere to be found (look again at the work of Werner but also the work of Jorda, Schularick and Taylor on this: nowadays, not the flow economy but the mortgage industry often is the main ‘money printing press’. The work of these economists (or Steve Keen) is, when compared with the ideas of John Stuart Mill and even Fisher, in fact much more ‘new classical’ than the official New Classical economic models.

The 64 trillion-dollar question is of course: why do Friedman and Schwarz discard modern monetary measurement and why do they stick to their CCA? Why don’t they mention Copeland and why don’t they even mention the Flow of Funds (which, again, is the cornerstone of modern monetary measurement)? Why didn’t they catch up with the developments in modern economic statistics taking place at the most important central banks of the world? Why did the bend over backwards to avoid any data and each author which hinted at, in the words of Minsky “a commercial loan monetary system … consistent with a debt deflation view of how major recessions are generated: a view in which the historically observed changes in the money supply, particularly those associated with deep depression, are a result of business behavior”?