From Gary Flomenhoft, “The triumph of Pareto”, real-world economics review, issue no. 80, 26 June 2017, pp. 14-31. There are several serious problems with the use of Pareto Optimality as the central goal of economics. One of the primary implications of “Pareto Optimality” is that it accepts the current distribution of wealth as a given. If any income distribution can lead to an “optimal” outcome, there is no need to be concerned about just distribution. Mainstream economists generally make no distinction between earned or unearned income, and when they do, it is typically to recommend lower taxes on the latter, a policy that has been adopted in the USA. Mainstream economists rarely question the legitimacy of the source of wealth. Fairness or origin of the current distribution is a

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Gary Flomenhoft, “The triumph of Pareto”, real-world economics review, issue no. 80, 26 June 2017, pp. 14-31.

There are several serious problems with the use of Pareto Optimality as the central goal of economics. One of the primary implications of “Pareto Optimality” is that it accepts the current distribution of wealth as a given. If any income distribution can lead to an “optimal” outcome, there is no need to be concerned about just distribution. Mainstream economists generally make no distinction between earned or unearned income, and when they do, it is typically to recommend lower taxes on the latter, a policy that has been adopted in the USA. Mainstream economists rarely question the legitimacy of the source of wealth. Fairness or origin of the current distribution is a problem left to politicians and society. It is not considered a legitimate question for economics. As Steven Hackett points out, “Slavery was widely seen in the North as being unethical from a deontological perspective, but a policy alternative of ending slavery would make slave owners worse off than under the status quo, and thus would have failed the Pareto efficiency criterion” (Hackett, 2001: 26).

While Pareto developed his theory of Optimality, he also described the idea of “indifference curves” in conjunction with Edgeworth, which captures each person’s preferences for different combinations of various goods. It established the idea of ordinal rather than cardinal welfare, and eliminated comparisons of utility between people. According to Pareto and current neo-classical orthodoxy, each person can only decide how well off they are “in their own estimation”. This avoids any consideration of justice in the current social conditions. In the words of Daly, “The extreme individualism of economics insists that people are so qualitatively different in their hermetical isolation one from another that it makes no sense to say that a leg amputation hurts Smith more than a pin prick hurts Jones” (Daly and Farley, 2010: 306).

Economics was originally based on classical utilitarianism, which followed the philosophy of “the greatest good for the greatest number”, and thus was very concerned with issues of distribution. Maximizing the total utility of society was the goal, and it was well understood that extra income provided more utility for a poor person than for a rich one.

Following Pareto, this was abandoned in favor of ordinal measures of welfare. Interpersonal comparisons of utility are still generally considered outside the bounds of neo-classical welfare economics.

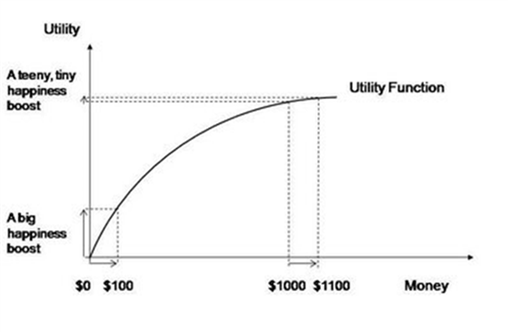

Utility curves of an individual assume diminishing marginal utility: the more of something a person has, the less utility an additional unit provides. Figure 1 below depicts the difference in utility from receiving $100 for a person with $1000 compared to the same person with $0. Is it really so far-fetched to believe that two human beings might have similar utility curves, especially when satisfying basic physiological needs? If this curve represented two people, rather than one person at different times, then the wealthier person obviously gets less utility from $100 than the poorer person. Economists can only accept Pareto efficiency as a central goal of economics by largely rejecting the notion of diminishing marginal utility.

Therefore Pareto Optimality is self-contradictory.

Figure 1 Interpersonal comparison of Utility

Source: http://mrski-apecon-2008.wikispaces.com/Sun%27s+Page.

One of the primary implications of Pareto optimality is that economists cannot pass judgment on the desirability of different distributions of wealth and income. “Potential Pareto optimality” relaxes this criterion by declaring one option superior to another if the winners could potentially compensate the losers through transfer payments, even if no compensation actually takes place (Kaldor-Hicks criteria). Actual compensation is left to society to take care of and is out of the realm of economics.

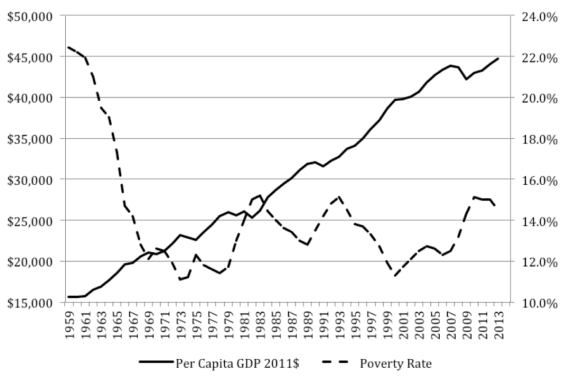

Economists’ obsession with Pareto optimality has led them to virtually ignore the welfare implications of upward and downward redistribution. If redistribution of the pie is considered off-limits, then the only option left for improving welfare is a bigger pie, typically measured by higher GDP. Also, since the measure of welfare is entirely subjective, how could one determine who feels better or worse? It’s much safer to assume that a rising tide lifts all boats, and don’t worry about the people with no boats. It is universally believed that we can grow our way out of poverty. Does reality support the myth? Prior to 1967 the poverty rate appeared to decline as GDP increased. However, as shown in Figure 2, since 1968 there has been no relationship between long term GDP growth and poverty alleviation as is commonly believed.

Figure 2 Poverty rate vs GDP

Source: Author from US Census Bureau data, 2014.

Even if growth did contribute to poverty alleviation it is questionable if it is a viable option any longer due to the limits of planetary growth. It would require an estimated 4.5 planets to extend current levels of US consumption of resources and emission of pollutants to all 7 billion people on the earth (Ewing et al., 2010).