From David Ruccio Over the years, I’ve reproduced and created many different charts representing the spectacular rise of inequality in the United States during the past four decades. Here’s the latest—based on the work of Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman—which, according to David Leonhardt, “captures the rise in inequality better than any other chart or simple summary that I’ve seen.” I agree. The chart shows the different rates of change in income between 1980 and 2014 for every point on the distribution. The brown line illustrates the change in the distribution of income in the 34 years before 1980, when those at the bottom saw larger growth than those at the top. In contrast, in the decades leading up to 2014, only those at the very top saw high levels of income

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Over the years, I’ve reproduced and created many different charts representing the spectacular rise of inequality in the United States during the past four decades.

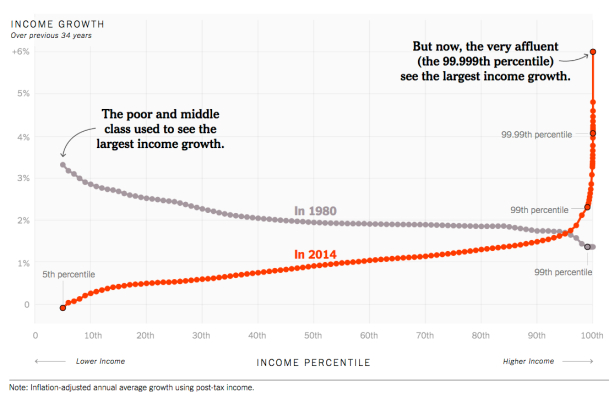

Here’s the latest—based on the work of Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman—which, according to David Leonhardt, “captures the rise in inequality better than any other chart or simple summary that I’ve seen.”

I agree.

The chart shows the different rates of change in income between 1980 and 2014 for every point on the distribution. The brown line illustrates the change in the distribution of income in the 34 years before 1980, when those at the bottom saw larger growth than those at the top. In contrast, in the decades leading up to 2014, only those at the very top saw high levels of income growth. Everyone else experienced very little gain.

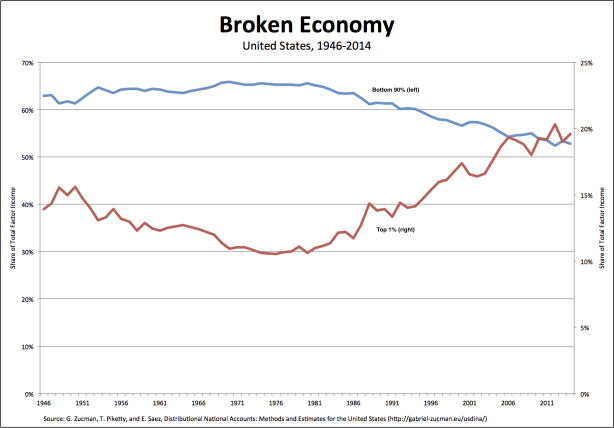

Lest we forget, however, the U.S. economy was already broken by 1980: the bottom 90 percent only took home about 65 percent of national income, while the top 1 percent managed to capture 10.6 percent of total income in the United States. There was nothing fair about that situation.

A bit like a car that looks good, when shiny and new, but is designed with cheap parts to fail as soon as the warranty expires.

Well, the warranty on the U.S. economy expired in the late 1970s. And then it really began to break down.

By 2014, that already-unequal distribution of income had become truly obscene: the share of income going to the bottom 90 percent had fallen to less than 53 percent, while the share captured by the top 1 percent had soared to over 19 percent.

Leonhardt is right: “there is nothing natural about the distribution of today’s growth — the fact that our economic bounty flows overwhelmingly to a small share of the population.”

Yes, as Leonhardt argues, different policies would produce a somewhat more equal outcome. And, it’s true, “President Trump and the Republican leaders in Congress are trying to go in the other direction.”

But a different economy—a radically different way of organizing economic and social life—would eliminate the conditions that led to unequalizing growth in the first place. Both before 1980 and in the decades since then.

The fact is, the supposed Golden Age of American capitalism was based on a set of institutions that allowed the boards of directors of large corporations to appropriate a growing surplus and to distribute it as they wished. At first, during the immediate postwar period, that meant growing incomes for those in the bottom 90 percent. But, even then, the mechanisms for distributing income remained in the hands of a very small group at the top. And they had both the interest and the means to stop the growth of wages, get even more surplus (from U.S. workers and, increasingly, workers around the globe), and distribute a greater share of that surplus to a tiny group at the very top of the distribution of income.

Those are the mechanisms that need to be challenged and changed. Otherwise, inequality will remain out of control.