From David Ruccio David Brooks should have left well enough alone. Middle-class wage stagnation is the biggest economic fact driving American politics. Over the past many years, so the common argument goes, capitalism has developed structural flaws. Economic gains are not being shared fairly with the middle class. Wages have become decoupled from productivity. Even when the economy grows, everything goes to the rich. But then Brooks spends the rest of his column trying to convince us that there aren’t any really structural flaws, that “the market is working more or less as it’s supposed to.” Well, maybe it’s working “more or less as it’s supposed to” for those at the top. But it’s certainly not working for everyone else, for those who actually have to work for a living. The

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

David Brooks should have left well enough alone.

Middle-class wage stagnation is the biggest economic fact driving American politics. Over the past many years, so the common argument goes, capitalism has developed structural flaws. Economic gains are not being shared fairly with the middle class. Wages have become decoupled from productivity. Even when the economy grows, everything goes to the rich.

But then Brooks spends the rest of his column trying to convince us that there aren’t any really structural flaws, that “the market is working more or less as it’s supposed to.”

Well, maybe it’s working “more or less as it’s supposed to” for those at the top. But it’s certainly not working for everyone else, for those who actually have to work for a living.

The relevant debate is all about wages and productivity.

For Brooks (and the mainstream economists whose work he relies on), wages aren’t growing not because something is wrong, but because productivity isn’t growing. Or in his inimitable, sloganeering fashion:

It’s not that a rising tide doesn’t lift all boats; it’s that the tide is not rising fast enough.

Except, of course, productivity has grown—and wages haven’t kept up. Not by a long shot!

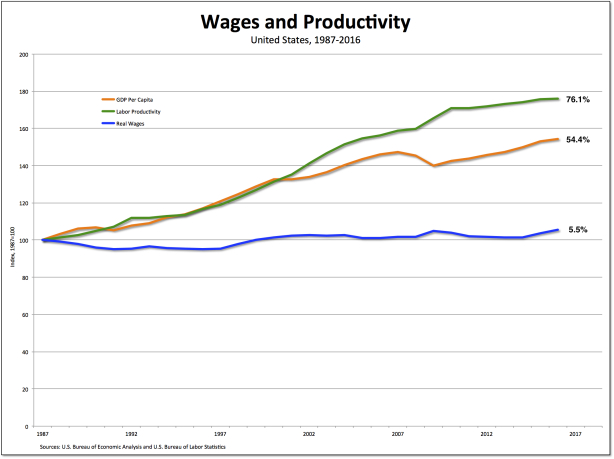

As is clear from the chart above, productivity has increased enormously since 1987—whether measured in terms of real GDP per capita (the orange line) or, even more, real nonfarm business output per hour worked (the green line).

So, yes, Americans have become more productive over the course of the past three decades. But wages have lagged far behind.

In fact, as is also clear in the chart, real wages (measured in terms of real weekly earnings, the blue line) have been virtually stagnant. They’ve risen only 5.5 percent over that period, much less than GDP per capita (54.4 percent) and labor productivity in nonfarm businesses (76.1 percent).

In the end, maybe Brooks is right. Maybe the growing gap between wages and productivity is not a structural flaw. Maybe it’s the way the market is supposed to work.

If so, then it’s time the break the system that both generates and relies on the large and growing gap between wages and productivity—the one Brooks and mainstream economists work so hard to convince us isn’t broken at all.

Our job, then, is to get to work imagining and creating a radically different economic and social system.