From David Ruccio The latest IMF Fiscal Monitor, “Tackling Inequality,” is out and it represents a direct challenge to the United States. It’s not just a rebuke to Donald Trump, who with his allies is pursuing under the guise of “tax reform” a set of policies that will lead to even greater inequality—or, for that matter, Republicans in state governments across the country that have sought to cut back on programs targeted at poor Americans. It also takes to task decades of growing inequality in the United States, under both Democratic and Republican administrations. As is clear from the chart above, the distribution of both income and wealth in the United States has become increasingly unequal since the mid-1970s. The share of income captured by the top 1 percent has more than

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

The latest IMF Fiscal Monitor, “Tackling Inequality,” is out and it represents a direct challenge to the United States.

It’s not just a rebuke to Donald Trump, who with his allies is pursuing under the guise of “tax reform” a set of policies that will lead to even greater inequality—or, for that matter, Republicans in state governments across the country that have sought to cut back on programs targeted at poor Americans. It also takes to task decades of growing inequality in the United States, under both Democratic and Republican administrations.

As is clear from the chart above, the distribution of both income and wealth in the United States has become increasingly unequal since the mid-1970s. The share of income captured by the top 1 percent has more than doubled (from 10 to 20 percent), while it’s share of total wealth has increased dramatically (from 23 percent to 39 percent). Meanwhile, the share of income of the bottom 50 percent has declined precipitously (from 20 percent to 12.5 percent) and it’s share of wealth, which was never very high (at 0.9 percent), is now nonexistent (at negative 0.1 percent).

And what is the United States doing about it? Absolutely nothing. Over the course of the past four decades it’s done very little to tackle the problem of growing inequality—and what it has done has been spectacularly ineffective. Thus, inequality has grown to obscene levels.

What’s interesting about the IMF report is that it raises—and then challenges—every important argument made by mainstream economists and members of the economic and political elite.

Should we worry just about income inequality? Well, no, since “changes in income inequality are reflected in other inequality dimensions, such as wealth inequality.”

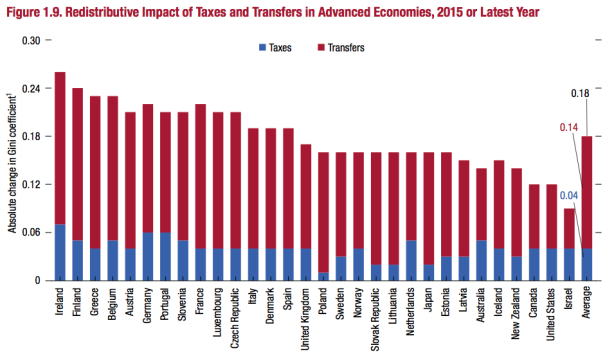

Doesn’t the United States take care of the problem by redistribution? Absolutely not, since only Israel does less than the United States in terms of lowering inequality (as measured by the Gini coefficient) through taxes and transfers.

But doesn’t tackling inequality through progressive income taxes lower economic growth? Again, no: “There is not strong empirical evidence showing that progressivity has been harmful for growth.”

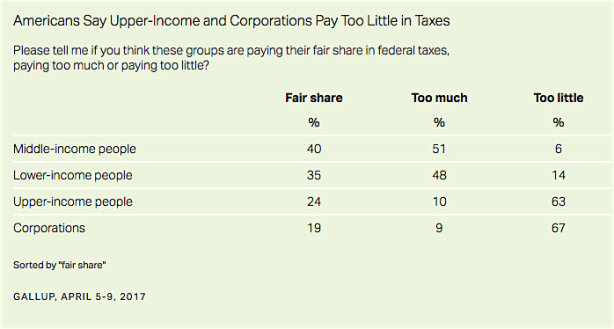

Nor is there any justification for low tax rates on those at the top in terms of social preferences. Most Americans, according to a recent Gallup survey, most believe that the rich and corporations don’t pay their fair share of taxes. In fact, the IMF notes, perhaps thinking about the United States, “societal preferences may not be reflected in actual policy implementation because of the concentration of political power in certain affluent groups.”

Clearly, much more can be done to lower the degree of inequality in the United States.

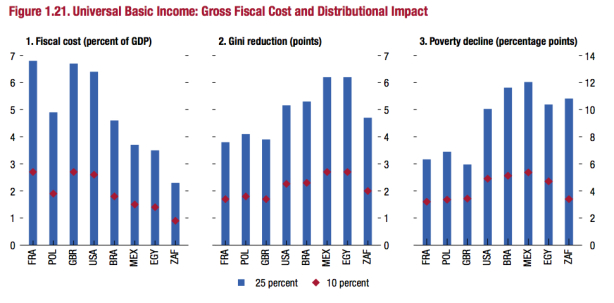

As a sign of the times, the IMF even chooses to discuss the role a Universal Basic Income might play in decreasing inequality.

Proponents argue that a UBI can be used as a redistributive tool to help address poverty and inequality better than means-tested programs, which su er from information constraints, high administrative costs, and other obstacles that limit benefit take-up. A UBI could also help address increased income uncertainty resulting from the impact of technology (particularly automation) on jobs.

According to its calculations, a Universal Basic Income in the United States (calibrated at 25 percent of median per capita income, in addition to existing programs) would cost only 6.5 percent of national income and achieve a remarkable reduction in both inequality (by more than 5 Gini points) and poverty (by more than 10 percentage points).

What puts the United States in stark relief is the whole panoply of inequality-reducing policies that are available—from more progressive income taxes and the adoption of wealth taxes to reducing gaps in education and health programs.

The problem, of course, is the United States is moving in the opposite direction. It is simply not tackling the problem, with the inevitable result: current levels of economic inequality are—by any measure, and especially in comparison to what could be but isn’t being done—grotesque.