From David Ruccio Liberal stories about who’s been left behind during the Second Great Depression are just about as convincing as the “breathtakingly clunky” 2014 movie starring Nicolas Cage. For Thomas B. Edsall, the story is all about the people in the “rural, less populated regions of the country” who have been left behind in the “accelerated shift toward urban prosperity and exurban-to-rural stagnation” and who supported Republicans in the most recent election. Louis Hyman, for his part, argues that the people who have been left behind—rural Americans and the people “who live and work in small towns”—hold a misplaced nostalgia for Main Street, which has been exploited by Donald Trump. What they really need, according to Hyman, is to find new jobs online so that they can “find their way from Main Street to the mainstream.” In both cases, and many more like them, the great divide is supposedly one of geography: everyone is prospering in the big cities—with high-tech jobs, soaring incomes, and a proliferation of non-chain boutiques and restaurants—and everyone else, outside those cities, is being left behind. Except, of course, nothing could be further from the truth. Yes, lots of people outside of the country’s metropolitan areas have been excluded from the recovery from the crash of 2007-08 (just as they were during the bubble that preceded it).

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Liberal stories about who’s been left behind during the Second Great Depression are just about as convincing as the “breathtakingly clunky” 2014 movie starring Nicolas Cage.

For Thomas B. Edsall, the story is all about the people in the “rural, less populated regions of the country” who have been left behind in the “accelerated shift toward urban prosperity and exurban-to-rural stagnation” and who supported Republicans in the most recent election.

Louis Hyman, for his part, argues that the people who have been left behind—rural Americans and the people “who live and work in small towns”—hold a misplaced nostalgia for Main Street, which has been exploited by Donald Trump. What they really need, according to Hyman, is to find new jobs online so that they can “find their way from Main Street to the mainstream.”

In both cases, and many more like them, the great divide is supposedly one of geography: everyone is prospering in the big cities—with high-tech jobs, soaring incomes, and a proliferation of non-chain boutiques and restaurants—and everyone else, outside those cities, is being left behind.

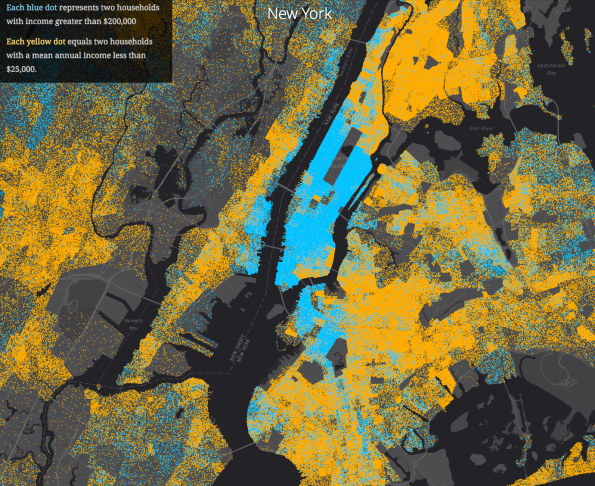

Except, of course, nothing could be further from the truth. Yes, lots of people outside of the country’s metropolitan areas have been excluded from the recovery from the crash of 2007-08 (just as they were during the bubble that preceded it). But that’s true also of cities themselves, from Boston to San Francisco.

The problem is not geography, but class.

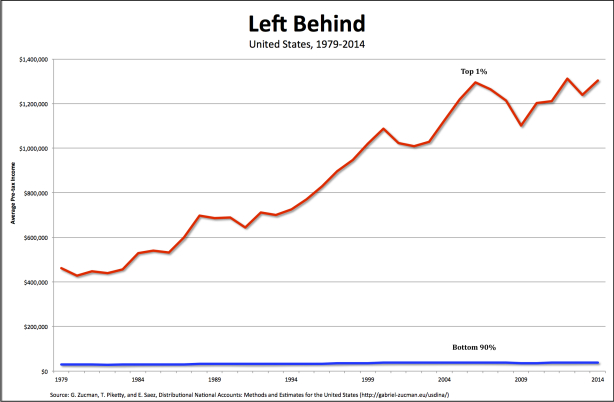

According to a 2016 report from the Economic Policy Institute, in almost half of U.S. states, the top 1 percent captured at least half of all income growth between 2009 and 2013, and in 15 of those states, the top 1 percent captured all income growth. In another 10 states, top 1 percent incomes grew in the double digits, while bottom 99 percent incomes fell.

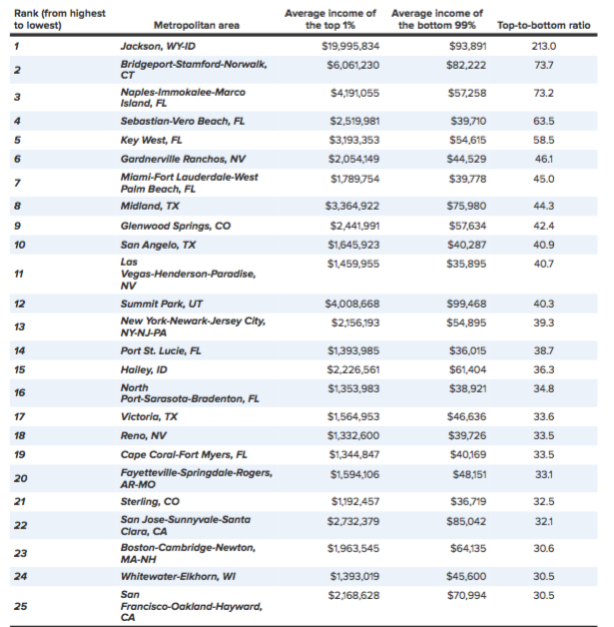

Much the same is true in the nation’s metropolitan areas. In the 12 most unequal metropolitan areas, the average income of the top 1 percent was at least 40 times greater than the average income of the bottom 99 percent. In the New York City area, the average income of the top 1 percent was 39.3 times the average income of the bottom 99 percent, in Boston 30.6, and in San Francisco, 30.5 times.

By the same token, some of the nation’s non-urban counties have very high levels of income inequality. Lasalle County, Texas, for example, has an average income of the bottom 90 percent of only $47,941 but a top-to-bottom ratio of 125.6. Similarly, Walton County Florida, with a bottom-90-percent income of $40,090, has a top-to-bottom ratio of 45.6.

The fact is, across the entire United States—in large cities as well in small towns and rural areas—the incomes of the top 1 percent have outpaced the gains of everyone else. That’s been the case during the recovery from the Great Recession, just as it was in the three decades leading up to the most recent crash.

While it’s true, the voters in most metropolitan areas went for Hillary Clinton and those elsewhere supported Trump. The irony is that the majority of those voters, inside and outside the nation’s cities, have been left behind by an economic system that benefits only those at the very top.