From David Ruccio One of the most pernicious myths in the United States is that higher education successfully levels the playing field across students with different backgrounds and therefore reduces wealth inequality. The reality is quite different—for the population as a whole and, especially, for racial and ethnic minorities. As is clear from the chart above, the share of wealth owned by the top 1 percent has risen dramatically since the mid-1970s, rising from 22.9 percent in 1976 to 38.6 percent in 2014. Meanwhile, the share owned by the bottom 90 percent has declined, falling from 34.2 percent to 27 percent. And that of the bottom 50 percent? It has remained virtually unchanged at a negligible amount, falling from 0.9 percent to zero. During that same period, according to the

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

One of the most pernicious myths in the United States is that higher education successfully levels the playing field across students with different backgrounds and therefore reduces wealth inequality.

The reality is quite different—for the population as a whole and, especially, for racial and ethnic minorities.

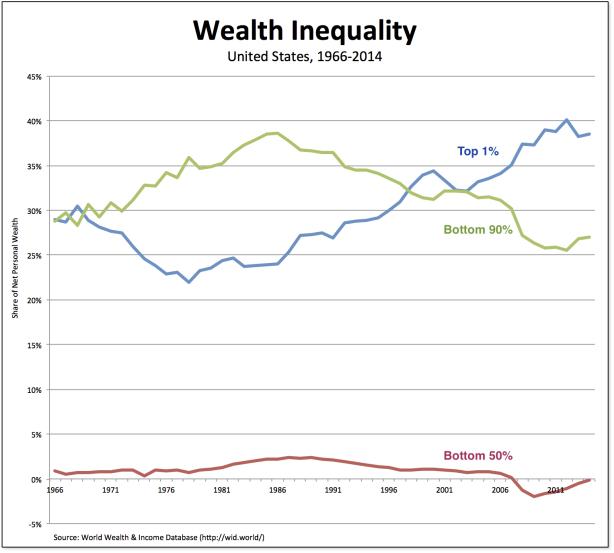

As is clear from the chart above, the share of wealth owned by the top 1 percent has risen dramatically since the mid-1970s, rising from 22.9 percent in 1976 to 38.6 percent in 2014. Meanwhile, the share owned by the bottom 90 percent has declined, falling from 34.2 percent to 27 percent. And that of the bottom 50 percent? It has remained virtually unchanged at a negligible amount, falling from 0.9 percent to zero.

During that same period, according to the U.S. Census Bureau (pdf), the proportion of Americans aged 25 to 29 with a bachelor’s degree or higher rose from 24 percent to 36 percent. (For the entire population 25 and older, the percentage with that level of education rose from 15 to 33.)

So, no, higher education has not leveled the playing field or reduced wealth inequality. In fact, it seems, quite the opposite appears to be the case.

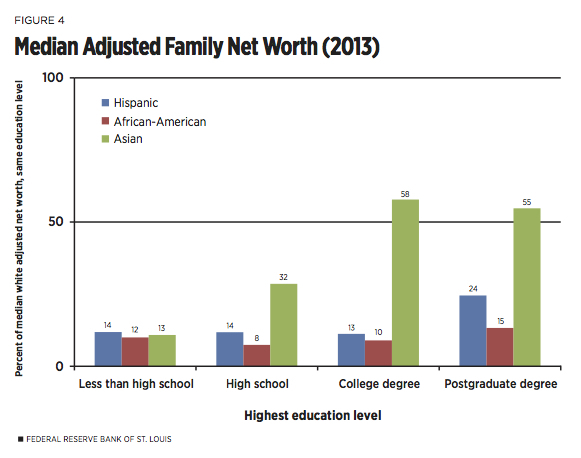

And that’s true, too, for racial and ethnic disparities in wealth. As William R. Emmons and Lowell R. Ricketts (pdf) of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis have concluded,

Despite generations of generally rising college-graduation rates, higher education’s promise of significantly reducing income and wealth disparities across all races and ethnicities remains largely unfulfilled. . .rather than promoting economic equality across all races and ethnicities, higher education unintentionally has become an engine for growing disparities.

Thus, for example, median Hispanic and black wealth levels decline relative to similarly educated whites as education increases until the very top. Moreover, only about 7 percent of black families and 5 percent of Hispanic families have postgraduate degrees, and wealth disparities remain large even there.

Darrick Hamilton and William A. Darity, Jr. (pdf), who participated in the same symposium, go even further. According to them, the United States has a fundamental problem in discussing wealth disparities according to race and ethnicity:

Much of the framing around wealth disparity, including the use of alternative financial service products, focuses on the poor financial choices and decisionmaking on the part of largely Black, Latino, and poor borrowers, which is often tied to a culture of poverty thesis regarding an undervaluing and low acquisition of education.

Thus, while they agree that a college degree is positively associated with wealth within racial and ethnic groups, it is still the case that it does little to address the massive wealth gap across such groups.

And yet the myth persists. American elites and policymakers still to choose to emphasize the economic returns to education as the panacea to address socially established wealth disparities and structural barriers of racial and ethnic economic inclusion.

The question is, why?

According to Hamilton and Darity, such a view

follows from a neoliberal perspective, where the free market, as long as individual agents are properly incentivized, is supposed to be the solution to all our problems, economic or otherwise. The transcendence of Barack Obama becomes the ideal symbolism and spokesperson of this political perspective. His ascendency becomes an allegory of hard work, merit, efficiency, social mobility, freedom and fairness, individual agency, and personal responsibility. The neoliberal ideology is not limited to race. It more generally places the onus on individual actions, and more broadly leads to deficiency narratives for low achievement, but this is especially the case when considering race and other stigmatized workers. Perhaps the greatest rhetorical victory of this paradigm is convincing the masses that implicit in unfettered markets is the “American Dream”—the hope that, even if your lot in life is subpar, with patience and individual hard work, you can turn your proverbial “rags into riches.”

And so the myth of college and the American Dream is perpetuated, while the unequal distribution of wealth—across the entire population, and especially with respect to ethnic and racial minorities—which has been growing for decades, continues unabated.