From David Ruccio Noah Smith is right about one thing: mainstream economists tend to use the word “capital” pretty loosely. It just means “anything you can spend resources to build, which lasts a long time, and which also can be used to produce value.” That’s really broad. For example, it could include society itself. It also typically includes “human capital,” which refers to people’s skills, talents, and knowledge. But then Smith proceeds, like the neoclassical equivalent of Humpty Dumpty, to make his definition of human capital the master—because, in his view, “it helps to convey some important truths about the world.” Human capital, as I’ve explained in some detail before, is a profoundly misleading concept. I don’t want to repeat those arguments here. But I do want to make two additional points. First, if Smith wants to invoke human capital to say “education and skills are a form of wealth,” then why not include other ways people are able to earn more or less than their counterparts? Why not, for example, go beyond his reference to credentials (he has a Stanford degree) and intellectual abilities (apparently, he can do math well and write well) and refer to some of the other important ways people are sorted out within existing economic relations. I’m thinking of such things as gender, race and ethnicity, immigration status, and so on.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Noah Smith is right about one thing: mainstream economists tend to use the word “capital” pretty loosely.

It just means “anything you can spend resources to build, which lasts a long time, and which also can be used to produce value.” That’s really broad. For example, it could include society itself. It also typically includes “human capital,” which refers to people’s skills, talents, and knowledge.

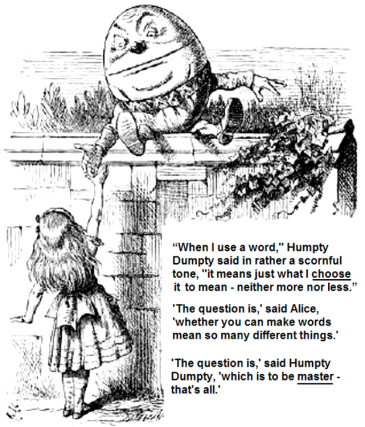

But then Smith proceeds, like the neoclassical equivalent of Humpty Dumpty, to make his definition of human capital the master—because, in his view, “it helps to convey some important truths about the world.”

But then Smith proceeds, like the neoclassical equivalent of Humpty Dumpty, to make his definition of human capital the master—because, in his view, “it helps to convey some important truths about the world.”

Human capital, as I’ve explained in some detail before, is a profoundly misleading concept.

I don’t want to repeat those arguments here. But I do want to make two additional points.

First, if Smith wants to invoke human capital to say “education and skills are a form of wealth,” then why not include other ways people are able to earn more or less than their counterparts? Why not, for example, go beyond his reference to credentials (he has a Stanford degree) and intellectual abilities (apparently, he can do math well and write well) and refer to some of the other important ways people are sorted out within existing economic relations. I’m thinking of such things as gender, race and ethnicity, immigration status, and so on. They’re all ways workers are able to receive more or less income that have nothing to do with the effort they put into their jobs. Does Smith want to argue that masculinity, whiteness, and native birth are forms of human capital?

No, I didn’t think so.

Second, there’s the issue of capital itself. When capital is treated as a thing (which is what one finds in Smith’s account, as in most versions of mainstream economics), then it’s possible to forget about or overlook the historical and social conditions necessary for those things to operate as capital. Buildings, machinery, and raw materials, robots and computer software, even skills, talents, and knowledge—they only operate as capital within particular economic relations. Only when workers are forced to have the freedom to sell their ability to work to a small group of employers, only then does capital become a means to extract surplus labor from those workers. Once appropriated, that surplus labor then assumes a variety of different, seemingly independent forms—from capitalist profits to land rents, including payments to merchants and finance, the super-profits of oligopolies, taxes to the state, and, yes, the salaries of CEOs and supervisors.

But those payments are not “returns” to independent forms of capital, human or otherwise. They’re all distributions of the surplus-value that both presume and produce the conditions under which laborers work not for themselves, but for their capitalist employers.

They, and not the various meanings neoclassical economists attribute to capital, are the real masters.