From David Ruccio I am quite willing to admit that, based on last Friday’s job report, the Second Great Depression is now over. As regular readers know, I have been using the analogy to the Great Depression of the 1930s to characterize the situation in the United States since late 2007. Then as now, it was not a recession but, instead, a depression. As I explain to my students in A Tale of Two Depressions, the National Bureau of Economic Research doesn’t have any official criteria for distinguishing an economic depression from a recession. What I offer them as an alternative are two criteria: (a) being down (as against going down) and (b) the normal rules are suspended (as, e.g., in the case of the “zero lower bound” and the election of Donald Trump). By those criteria, the United

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

I am quite willing to admit that, based on last Friday’s job report, the Second Great Depression is now over.

As regular readers know, I have been using the analogy to the Great Depression of the 1930s to characterize the situation in the United States since late 2007. Then as now, it was not a recession but, instead, a depression.

As I explain to my students in A Tale of Two Depressions, the National Bureau of Economic Research doesn’t have any official criteria for distinguishing an economic depression from a recession. What I offer them as an alternative are two criteria: (a) being down (as against going down) and (b) the normal rules are suspended (as, e.g., in the case of the “zero lower bound” and the election of Donald Trump).

By those criteria, the United States experienced a second Great Depression starting in December 2007 and continuing through April 2017. That’s almost a decade of being down and suspending the normal rules!

Now, with the official unemployment rate having fallen to 4.4 percent, equal to the low it had reached in May 2007, we can safely say the Second Great Depression has come to an end.

However, that doesn’t mean we’re out of the woods, or that we can forget about the effects of the most recent depression on American workers.*

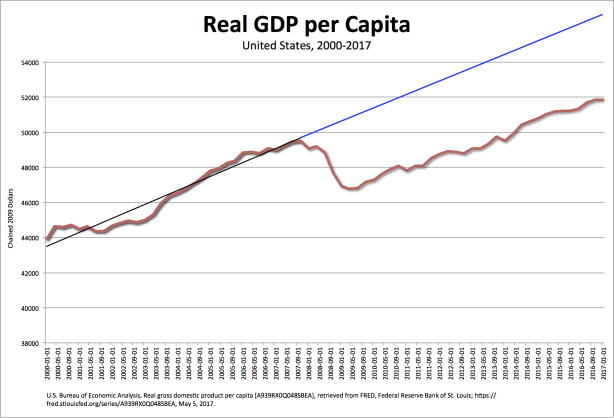

For example, while Gross Domestic Product per capita in the United States is higher now than it was at the end of 2007 ($51,860 versus $49,586, in chained 2009 dollars, or 4.6 percent), it is still much lower than it would have been had the previous trend continued (which can be seen in the chart above, where I extend the 2000-2007 trend line forward to 2017). All that lost output—not to mention the accompanying jobs, homes, communities, and so on—represents one of the lingering effects of the Second Great Depression.

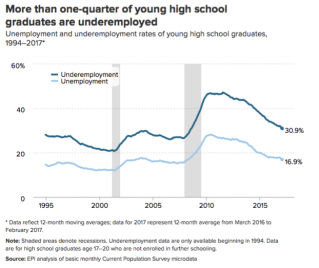

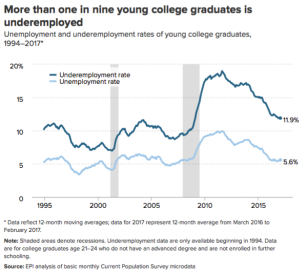

And we can’t forget that young workers face elevated rates of underemployment—11.9 percent for young college graduates and much higher, 30.9 percent, for young high-school graduates. As the Economic Policy Institute observes,

This suggests that young graduates face less desirable employment options than they used to in response to the recent labor market weakness for young workers.

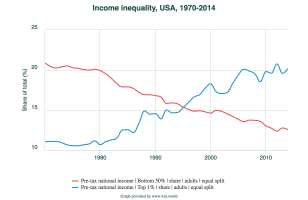

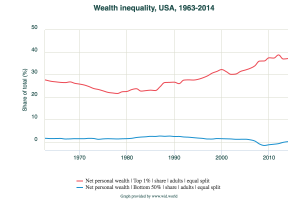

Finally, the previous trend of growing inequality—in terms of both income and wealth—has continued during the Second Great Depression. And there are no indications from the economy or economic policy that suggest that trend will be reversed anytime soon.

So, here we are at the end of the Second Great Depression—no longer down and with the normal rules back in place—and yet the effects from the longest and most severe downturn since the 1930s will be felt for generations to come.

*As if often the case, readers’ comments on newspaper articles tell a different story from the articles themselves. Here are two, on the New York Times article about the latest employment data:

John Schmidt—

Any discussion about “full employment”, when there are so many people who’ve essentially given up looking for work or who’re working in low-skill or unskilled labor positions, seems like the fiscal equivalent of rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. Based on data from the Fed and the World Bank, GDP per capita has doubled since 1993, while median household income has risen ~10%. Most of the newly-generated wealth and gains from productivity increases are being funneled upward, such that the average worker very rarely sees any sort of pay increase. Are we expected to believe that this will change now that we’ve [arguably] passed some arbitrary threshold? Why should we pat ourselves on the back for reaching “full employment”? Shouldn’t we be seeking *fulfilling* employment for everyone, instead, at least inasmuch as that’s possible? Shouldn’t we care that the relentless drive for profit at the expense of everything else is creating a toxic environment where the only way to ensure a raise is to hop from job to job, eroding any sense of two-way loyalty between companies and their employees?

I’m not sure what the solution is, but I know enough to see there’s a problem. Inequality of this sort is not sustainable, and it’s not going to magically disappear without some serious policy changes.

David Dennis—

There is a critical parameter missing from full employment data. very critical. Here in Pontiac, Michigan before the collapse of American manufacturing, full employment meant 10, 000 jobs working at GM factories and Pontiac Motors making above the mean wages with excellent health insurance as well as retirement pensions. You can not compare full employment at McDonalds and Walmart with the jobs that preceded them. The full employment measure doesn’t mean much if it isn’t correlated with a index that compares that employment with a standard of living as it relates to a set basket of goods, services, and benefits.