From David Ruccio Is it any surprise, as Christina Starman, Mark Sheskin, and Paul Bloom argue, that fairness is not the same thing as equality? There is immense concern about economic inequality, both among the scholarly community and in the general public, and many insist that equality is an important social goal. However, when people are asked about the ideal distribution of wealth in their country, they actually prefer unequal societies. We suggest that these two phenomena can be reconciled by noticing that, despite appearances to the contrary, there is no evidence that people are bothered by economic inequality itself. Rather, they are bothered by something that is often confounded with inequality: economic unfairness. Still, I think, many people today are bothered by both—economic unfairness and grotesque levels of economic inequality. Let me explain. As I have written before, I’m not particularly convinced of the idea being promoted by Starman et al. and by other evolutionary psychologists that fairness is part of humans’ biological inheritance. Instead, I’m more inclined to look in the direction of history and society. Fairness is, I think, a concept that is part of bourgeois society, which is created and disseminated in a wide variety of discourses and sites, including economics.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Is it any surprise, as Christina Starman, Mark Sheskin, and Paul Bloom argue, that fairness is not the same thing as equality?

There is immense concern about economic inequality, both among the scholarly community and in the general public, and many insist that equality is an important social goal. However, when people are asked about the ideal distribution of wealth in their country, they actually prefer unequal societies. We suggest that these two phenomena can be reconciled by noticing that, despite appearances to the contrary, there is no evidence that people are bothered by economic inequality itself. Rather, they are bothered by something that is often confounded with inequality: economic unfairness.

Still, I think, many people today are bothered by both—economic unfairness and grotesque levels of economic inequality.

Let me explain. As I have written before, I’m not particularly convinced of the idea being promoted by Starman et al. and by other evolutionary psychologists that fairness is part of humans’ biological inheritance. Instead, I’m more inclined to look in the direction of history and society.

Fairness is, I think, a concept that is part of bourgeois society, which is created and disseminated in a wide variety of discourses and sites, including economics. (To be clear, there may be other notions of fairness in human history, outside and beyond bourgeois society. My point is only that capitalism has its own particular notions of fairness, and they’re the ones that motivate our current “fairness instinct.”)

Fairness is an important part of the self-justification of bourgeois society. For example, market outcomes are considered fair because sovereign individuals are free to engage in voluntary transactions, which result in equal exchanges. That’s an idea that is created and reproduced throughout contemporary society, especially in mainstream economics.

So, yes, individuals within contemporary capitalism are constituted, at least in part, by certain notions of fairness, which they express in a wide variety of contexts, from participating in the ultimatum game to making a distinction between “takers” and “makers.”

By the same token, it’s not particularly shocking that those same individuals agree there should be some degree of inequality in economic outcomes. That’s also part of capitalism’s self-justification, that “fair” processes will produce unequal results. So, people seem to agree, not everyone can or should receive the same income or have the same wealth. We have different abilities, needs, desires, and circumstances, so the discourse goes, resulting in—perhaps even requiring—different amounts of income and wealth.

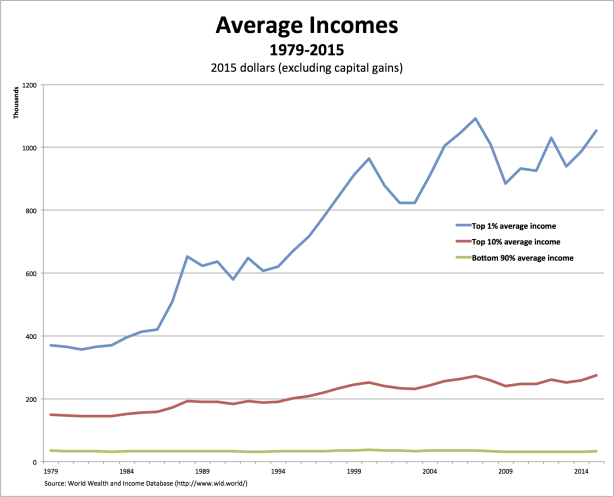

But then, of course, income inequalities have become so obscene—so unjustified by any conceivable differences in abilities, needs, desires, and circumstances—that, in the name of fairness, people demand more equality.

That’s how I think we need to reconcile the ideas of fairness and equality—not, as Starman et al. would have it, that people are bothered by fairness but not by inequality, but instead that bourgeois notions of fairness are so challenged and disrupted by existing levels of inequality people demand perhaps not perfect but certainly much more equality than exists today.

The real question is not whether there’s a “universal moral concern with fairness.” Instead, it’s whether the existing system can deliver on its promise to create fair (and, with them, more equal) outcomes—or, alternatively, whether it’s necessary to imagine and create a different set of economic and social institutions, which will actually fulfill that promise of fairness and at the same time deliver much more equality than exists in the United States today.