From David Ruccio Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations makes for uncomfortable reading these days. That’s because, as my students this semester have learned, the father of modern mainstream economics—who has become so closely (and mistakenly) identified with the invisible hand—held a narrow theory of money and advocated extensive regulation of the banking sector. This is contrast to the obscene growth of banking in recent decades, which Rana Foroohar reminds “isn’t serving us, we’re serving it.” According to Smith, the “judicious operations of banking” did nothing more than convert dead stock into active and productive stock—”into stock which produces something to the country.” The gold and silver money which circulates in any country may very properly be compared to a highway, which, while

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations makes for uncomfortable reading these days. That’s because, as my students this semester have learned, the father of modern mainstream economics—who has become so closely (and mistakenly) identified with the invisible hand—held a narrow theory of money and advocated extensive regulation of the banking sector.

This is contrast to the obscene growth of banking in recent decades, which Rana Foroohar reminds “isn’t serving us, we’re serving it.”

According to Smith, the “judicious operations of banking” did nothing more than convert dead stock into active and productive stock—”into stock which produces something to the country.”

The gold and silver money which circulates in any country may very properly be compared to a highway, which, while it circulates and carries to market all the grass and corn of the country, produces itself not a single pile of either. The judicious operations of banking, by providing, if I may be allowed so violent a metaphor, a sort of waggon-way through the air, enable the country to convert, as it were, a great part of its highways into good pastures and corn-fields, and thereby to increase very considerably the annual produce of its land and labour.

Moreover, Smith also argued, banks were susceptible to speculative crises. Thus, even in his system of “natural liberty,” the banking sector needed to be regulated, in order to lessen the likelihood of such crises and to minimize the suffering of the poor when they did happen.

To restrain private people, it may be said, from receiving in payment the promissory notes of a banker, for any sum whether great or small, when they themselves are willing to receive them, or to restrain a banker from issuing such notes, when all his neighbours are willing to accept of them, is a manifest violation of that natural liberty which it is the proper business of law not to infringe, but to support. Such regulations may, no doubt, be considered as in some respects a violation of natural liberty. But those exertions of the natural liberty of a few individuals, which might endanger the security of the whole society, are, and ought to be, restrained by the laws of all governments, of the most free as well as of the most despotical. The obligation of building party walls, in order to prevent the communication of fire, is a violation of natural liberty exactly of the same kind with the regulations of the banking trade which are here proposed.

Those warnings and regulations, of course, disappeared from contemporary mainstream economics—even as the financial sector continued to increase in size and significance within the U.S. economy.

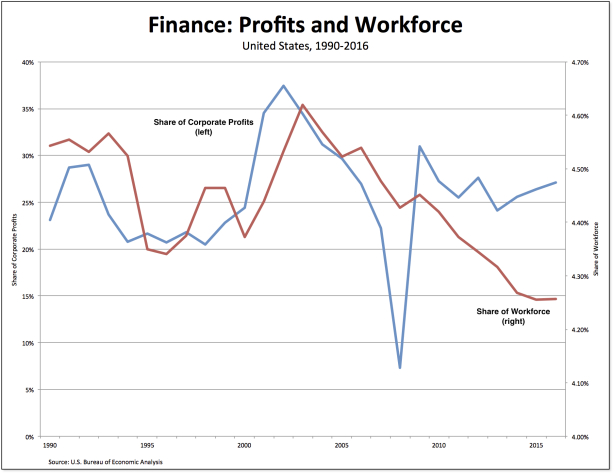

Today, financial profits (the blue line in the chart above) represent more than a quarter of total corporate profits in the United States, although the financial sector provides only 4.3 percent of American jobs (the red line in the chart).

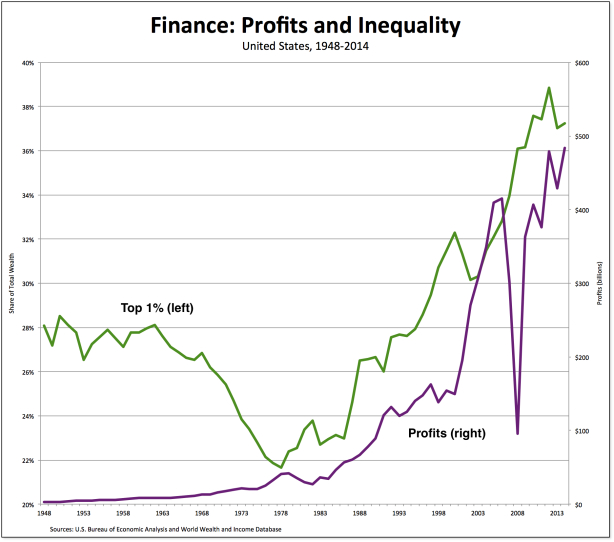

Moreover, as the profits of the financial sector (the purple line in the chart above) have grown—reaching still another record high of more than $500 billion in 2016—the distribution of wealth has become more and more unequal—such that, in 2016, the share of total wealth owned by the top 1 percent (the green line in the chart) was more than 37 percent.

And it’s not just the financial sector. As Forohoor explains, corporations outside the banking sector are copying the spectacularly successful model:

Nonfinancial firms as a whole now get five times the revenue from purely financial activities as they did in the 1980s. Stock buybacks artificially drive up the price of corporate shares, enriching the C-suite. Airlines can make more hedging oil prices than selling coach seats. Drug companies spend as much time tax optimizing as they do worrying about which new compound to research. The largest Silicon Valley firms now use a good chunk of their spare cash to underwrite bond offerings the same way Goldman Sachs might.

The fact is, financial wheeling and dealing has—after a brief interlude—returned as the tail that wags the economic dog in the United States. It manages to capture an outsized share of profits, even as it creates increased instability and obscene levels of inequality.

It should be clear to all that finance has been fundamentally transformed since Smith’s day, from a highway that was supposed to serve us into a master that we serve.