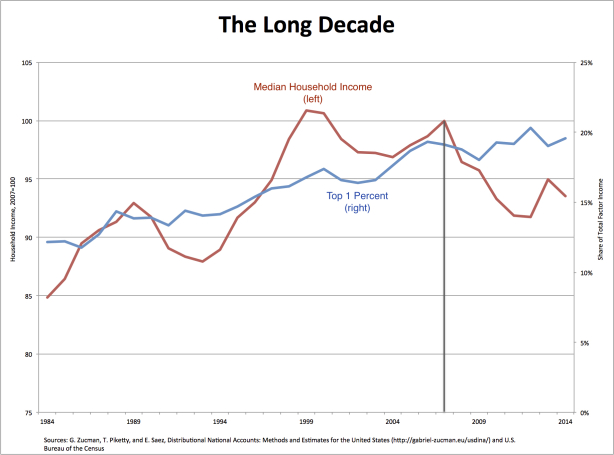

From David Ruccio Narayana Kocherlakota, professor of economics at the University of Rochester and past president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, is right: in some ways, the 2007-08 was worse than the Great Depression. It certainly has been worse for average households in the United States. Real median household income (the red line in the chart above) is still below what it was in 2007—and lower still from what it was even earlier, in 1999. But it hasn’t been a lost decade for the members of the top 1 percent. Their share of income (the blue line in the chart above), which was already an obscene 19 percent in 2007, is today even higher, at 19.6 percent.* Still, Kocherlakota’s warning is appropriate: financial crises and the responses to them can have highly persistent

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Narayana Kocherlakota, professor of economics at the University of Rochester and past president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, is right: in some ways, the 2007-08 was worse than the Great Depression.

It certainly has been worse for average households in the United States. Real median household income (the red line in the chart above) is still below what it was in 2007—and lower still from what it was even earlier, in 1999.

But it hasn’t been a lost decade for the members of the top 1 percent. Their share of income (the blue line in the chart above), which was already an obscene 19 percent in 2007, is today even higher, at 19.6 percent.*

Still, Kocherlakota’s warning is appropriate:

financial crises and the responses to them can have highly persistent adverse effects on economic potential. The risk of such large costs means that policy makers must have better safeguards in place, and be willing to respond vigorously through monetary and fiscal stimulus when crises nonetheless happen.

So what’s happening along these lines? The Trump administration’s nominee to be vice chair of supervision and regulation at the Federal Reserve wants to make the big banks’ stress tests less stringent — and that’ll make a financial crisis more, not less, likely. . .

In short, I see little evidence that policymakers have learned the lessons of the last decade. I hope that situation will change before another crisis occurs.

*Both of the data series represented in the chart above end in 2014. That’s because the series on the share of income captured by the top 1 percent ends in that year. Median household income in 2015, the last year for which those data are available, was still below what it was in 2007.

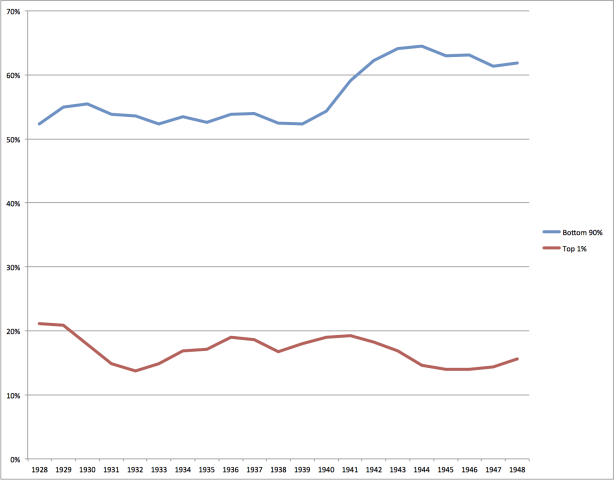

We don’t have comparable data series for the first Great Depression.

What we do know is that the share of income of the bottom 90 percent, which was 52.4 percent in 1928, hovered at roughly the same level throughout the 1930s, ending the decade at 52.5 percent, and then rose dramatically beginning in 1940. Meanwhile, the share of income captured by the top 1 percent, which stood at 21.2 percent in 1928, never managed to rise to that level during the 1930s and, by 1948, it had fallen to 15.6 percent.