From David Ruccio Over the course of the last two days, I’ve discussed mean gifts (which promise significant tax relief only to a small group of corporations and wealthy individuals) and mean exchanges (which leave middle-class Americans with a declining share of national income). Now, thanks to recently completed Reuters investigation, we’re forced to confront the reality in the United States of mean exchanges that transform generous donations into desperate, mean gifts. I’m referring to the largely unregulated trade in body parts. The selling of body parts—heads, knees, feet, torsos, and entire bodies—actually begins with the gifting of the bodies of deceased Americans, who have decided to donate their bodies to science. But in many cases it’s a mean gift, not because of the

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Over the course of the last two days, I’ve discussed mean gifts (which promise significant tax relief only to a small group of corporations and wealthy individuals) and mean exchanges (which leave middle-class Americans with a declining share of national income).

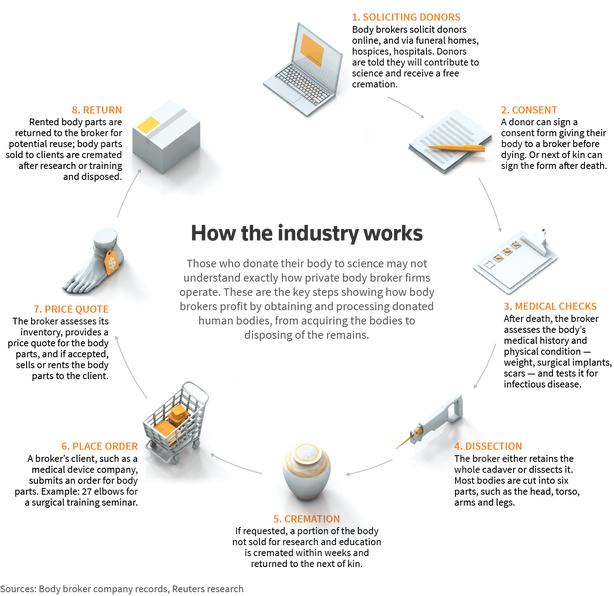

Now, thanks to recently completed Reuters investigation, we’re forced to confront the reality in the United States of mean exchanges that transform generous donations into desperate, mean gifts. I’m referring to the largely unregulated trade in body parts.

The selling of body parts—heads, knees, feet, torsos, and entire bodies—actually begins with the gifting of the bodies of deceased Americans, who have decided to donate their bodies to science. But in many cases it’s a mean gift, not because of the intentions of the givers (who in many cases do want to contribute to the advancement of the scientific study of the human body), but because body brokers often prey on poor people (who can’t afford the price of a proper burial).

The industry’s business model hinges on access to a large supply of free bodies, which often come from the poor. In return for a body, brokers typically cremate a portion of the donor at no charge. By offering free cremation, some deathcare industry veterans say, brokers appeal to low-income families at their most vulnerable. Many have drained their savings paying for a loved one’s medical treatment and can’t afford a traditional funeral.

“People who have financial means get the chance to have the moral, ethical and spiritual debates about which method to choose,” said Dawn Vander Kolk, an Illinois hospice social worker. “But if they don’t have money, they may end up with the option of last resort: body donation.”

Then, the body brokers—aka non-transplant tissue banks (that are distinct from organ and tissue transplant banks, which the U.S. government closely regulates)—turn around and sell or rent bodies and body parts for use in research or education.*

“The current state of affairs is a free-for-all,” said Angela McArthur, who directs the body donation program at the University of Minnesota Medical School and formerly chaired her state’s anatomical donation commission. “We are seeing similar problems to what we saw with grave-robbers centuries ago,” she said, referring to the 19th-century practice of obtaining cadavers in ways that violated the dignity of the dead.

“I don’t know if I can state this strongly enough,” McArthur said. “What they are doing is profiting from the sale of humans.”

The body brokers can charge what they want to for cadavers or deceased body parts. They negotiate prices with with research facilities—$250 for a hand, $450 for a knee, $5000 for a whole body—and even put their inventory on sale when they become overstocked.

The result is a profitable exchange for the body brokers—who of course are getting their raw materials for free—and the destruction of the gifts people have attempted to make to science.

Gail Williams-Sears, a nurse in Newport News, Virginia, said neither she nor her father realized Science Care might profit when he donated his body before his death in 2013. John M. Williams Jr, who lived 88 years, served in World War II and the Korean War, earned a master’s degree in social work and spent decades in Maryland state government advocating for children.

“Dad was very frugal,” his daughter said. “He thought it was ridiculous to pay a large amount of money to be put in the ground.” His decision to donate his body was also motivated by a lifelong interest in good health, his Christian faith and science fiction books and movies, she said. Whenever he was admitted to the hospital, he made sure to bring the donor documents with him, in case he died, his daughter said.

“I don’t remember anything in the literature that said anything about them selling his body,” she said. “I thought it was just his body going for research and it wasn’t to get gains off of someone’s charity. Well, I guess we’ve gotten to a world where everybody just makes money off of everything.”

The United States is now based on an economy in which many people can’t afford to die, and whose final gifts to science are annulled by the profit-making exchanges of largely unregulated body brokers.

*Selling hearts, kidneys and tendons for transplant is illegal in the United States. But no federal law governs the sale of cadavers or body parts to academic, medical, or scientific facilities.