From David Ruccio They keep promising, ever since the recovery from the Great Recession started more than eight years ago, that workers’ wages will finally begin to increase. But they’re not. Sure, profits continue to rise. And so is the stock market. But not wages. And mainstream economists can’t come up with an adequate explanation of why that’s the case. We’ve all heard or read the story. According to mainstream economists, as the unemployment rate falls (the blue line in the chart above), a labor shortage will be created and workers’ wages (the red line) will begin to rise. That’s the promise, at least. But the official unemployment rate is now down to 4.4 percent (from a high of 9.9 percent in 2009) and yet wages (for production and nonsupervisory workers) are only increasing

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

They keep promising, ever since the recovery from the Great Recession started more than eight years ago, that workers’ wages will finally begin to increase. But they’re not.

Sure, profits continue to rise. And so is the stock market. But not wages. And mainstream economists can’t come up with an adequate explanation of why that’s the case.

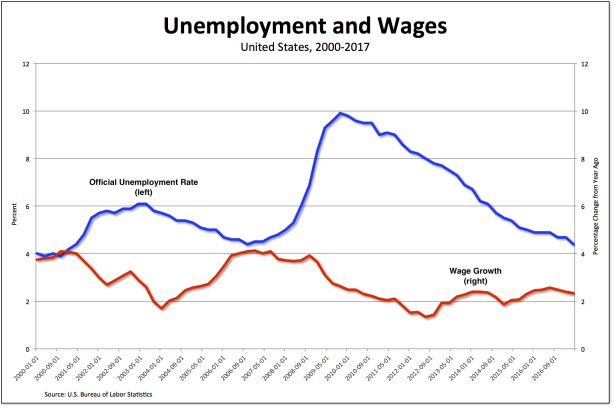

We’ve all heard or read the story. According to mainstream economists, as the unemployment rate falls (the blue line in the chart above), a labor shortage will be created and workers’ wages (the red line) will begin to rise.

That’s the promise, at least. But the official unemployment rate is now down to 4.4 percent (from a high of 9.9 percent in 2009) and yet wages (for production and nonsupervisory workers) are only increasing at a rate of 2.3 percent a year—much less than the 4 percent workers saw back in 2007 when the unemployment rate was pretty much the same.

What’s going on?

One of the things going on is the Reserve Army. The existence of a large pool of unemployed and underemployed workers competing with other workers for the available jobs is keeping wage growth at a very low rate.

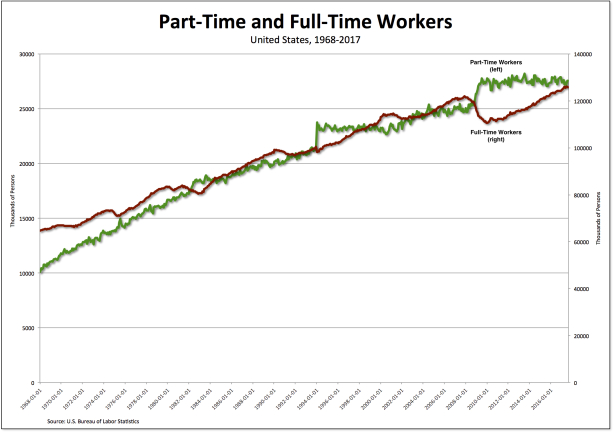

Consider, for example, the growth of full-time (the green line in the chart above) and part-time work (the purple line) in the United States. Since 1968, the two kinds of employment increased more or less simultaneously—until the most recent crash. Notice in the chart that, as full-time employment fell (from 121.9 million in 2007 to 111 million in 2010), part-time employment soared (from 24.7 million to 27.4 million). But then, even as full-time work began to increase again (reaching 125.8 million in August 2017), part-time employment remained high (27.6 million in that same month).

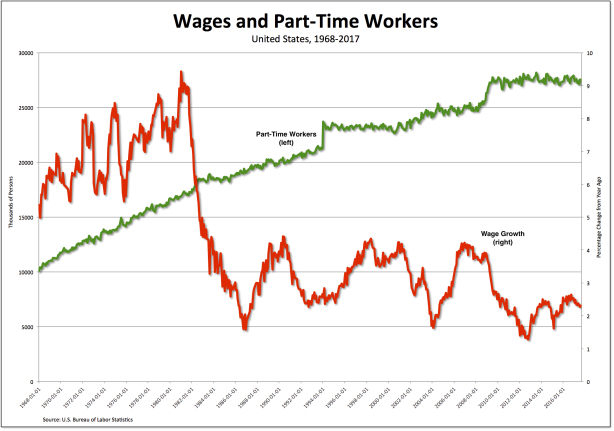

And it’s that pool of part-time American workers (in addition to the pool of surplus workers in other countries, increased automation, and low wages in the retail and food-service sectors) that is keeping most workers’ wages from growing.

Mainstream economists keep promising the American working-class an increase in wages. But neither they nor the economic system they celebrate is able to deliver on those promises.

The fact is, the longer those promises are proffered but remain unmet, the more frustrated workers will become. And the more likely it is they will demand a solution—a radically different economic system that doesn’t rely on a Reserve Army and can actually deliver on its promises to workers.