From David Ruccio I find myself thinking more these days about the fairness of Social Security and other government retirement benefits. One reason, of course, is because I’m getting close to retirement age—and, as I discover each time I raise the issue with students, young people don’t think about it much.* Another reason is because Social Security (in addition to Medicare, Disability, and other programs) is the way the United States creates a collective bond between current and former workers, by using a portion of the surplus produced by current workers to provide a safety net for workers who have retired. That represents a kind of social fairness—that people who have spent a large portion of their lives working (most people need 40 credits, based on years of work and earnings, to qualify for full Social Security benefits) are eligible for government retirement benefits provided by current workers. Another aspect of that fairness is the system should and does redistribute from those with high lifetime incomes to those with lower lifetime incomes. While that makes the actual “rates of return” unequal across groups, it’s designed to provide a floor for the poorest workers in society. Many people consider the U.S. Social Security system fair on those two grounds. That’s true even though some people, by random draw, may live longer than others. However, as Alan J.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

I find myself thinking more these days about the fairness of Social Security and other government retirement benefits.

One reason, of course, is because I’m getting close to retirement age—and, as I discover each time I raise the issue with students, young people don’t think about it much.* Another reason is because Social Security (in addition to Medicare, Disability, and other programs) is the way the United States creates a collective bond between current and former workers, by using a portion of the surplus produced by current workers to provide a safety net for workers who have retired.

That represents a kind of social fairness—that people who have spent a large portion of their lives working (most people need 40 credits, based on years of work and earnings, to qualify for full Social Security benefits) are eligible for government retirement benefits provided by current workers. Another aspect of that fairness is the system should and does redistribute from those with high lifetime incomes to those with lower lifetime incomes. While that makes the actual “rates of return” unequal across groups, it’s designed to provide a floor for the poorest workers in society.

Many people consider the U.S. Social Security system fair on those two grounds. That’s true even though some people, by random draw, may live longer than others. However, as Alan J. Auerbach et al. (pdf [ht: lw]) report, that fairness may be put into question if there are identifiable groups that vary in life expectancy, “as this introduces a non-random aspect to the inequality.”

Here’s the problem: retirement benefits in the United States are increasingly unequally distributed on a non-random basis. As I’ve written about many different times (e.g., here, here, and here), there’s a gap in life expectancies between those at the bottom and top of the distribution of income. And the gap has been growing over time.

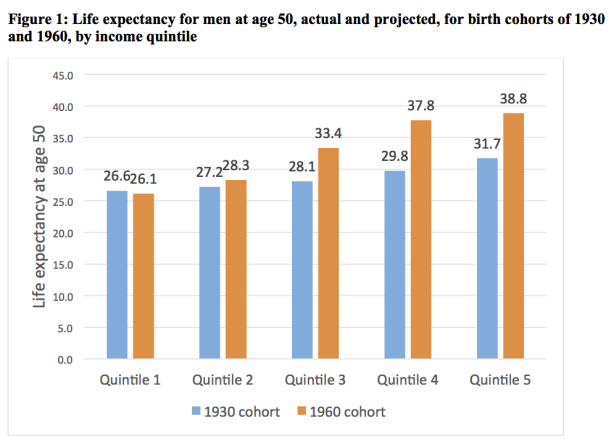

That result is confirmed by Alan J. Auerbach et al.: for the male birth cohort of 1930, life expectancy at age 50 rises from 26.6 to 31.7—a difference of 5.1 years. For the 1960 cohort, the lowest quintile has a slightly lower life expectancy than the 1930 cohort but then rises a level of 12.7 years higher for the top quintile, “indicating a very large increase in the dispersion.”

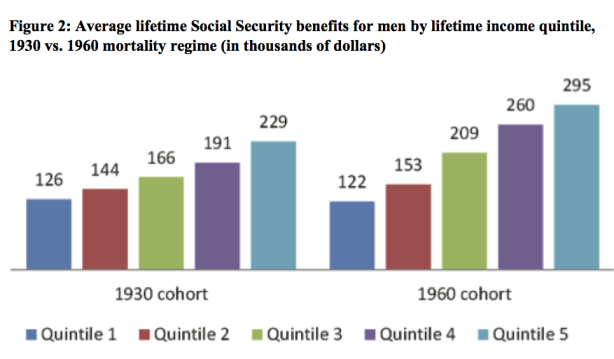

Not surprisingly (since benefits rise with earnings), Social Security benefits also rise with income quintiles. Thus, for example, for men in the 1930 cohort, workers in the lowest quintile can expect to receive, on average, $126 thousand in benefits over the rest of their lives (discounted to age 50), while workers in the top quintile can expect to receive $229 thousand, or 82 percent more than the lowest income workers.

What is particularly troubling is how the results change when we move to the 1960 cohort. The additional 6-8 years of life expectancy for the top three quintiles lead to large increases in expected Social Security benefits, with benefits for the top quintile reaching $295 thousand. The difference between the highest and lowest quintiles is then expected to be $173 thousand, or 142 percent of the lowest income workers’ benefit.

According to the authors of the study,

These results suggest that Social Security is becoming significantly less progressive over time due to the widening gap in life expectancy.

Not only does the growing gap in life expectancies undermine the basic fairness of the Social Security system. It calls into question capitalism itself.

*For understandable reasons. I certainly didn’t think about retirement at that age. (I barely thought about getting a job. I just presumed I would—and would be able to—at some point.) However, when students are induced to do think about retirement, as I’ve written before, most take it for granted that Social Security is doomed. While they expect to pay into Social Security, they don’t expect to receive any Social Security benefits when they retire. Then, of course, I explain to them that making only one change—raising the taxable earnings base—would eliminate the projected deficit and keep Social Security solvent forever.