From David Ruccio Everyone, it seems, now agrees that there’s a fundamental problem concerning wages and productivity in the United States: since the 1970s, productivity growth has far outpaced the growth in workers’ wages.* Even Larry Summers—who, along with his coauthor Anna Stansbury, presented an analysis of the relationship between pay and productivity last Thursday at a conference on the “Policy Implications of Sustained Low Productivity Growth” sponsored by the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Thus, Summers and Stansbury (pdf) concur with the emerging consensus, After growing in tandem for nearly 30 years after the second world war, since 1973 an increasing gap has opened between the compensation of the average American worker and her/his average labor

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

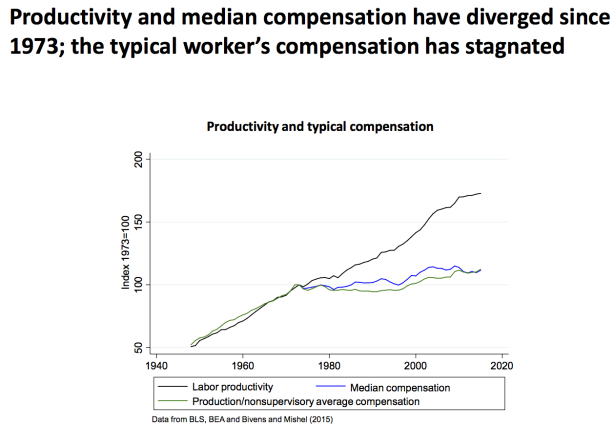

Everyone, it seems, now agrees that there’s a fundamental problem concerning wages and productivity in the United States: since the 1970s, productivity growth has far outpaced the growth in workers’ wages.*

Even Larry Summers—who, along with his coauthor Anna Stansbury, presented an analysis of the relationship between pay and productivity last Thursday at a conference on the “Policy Implications of Sustained Low Productivity Growth” sponsored by the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Thus, Summers and Stansbury (pdf) concur with the emerging consensus,

After growing in tandem for nearly 30 years after the second world war, since 1973 an increasing gap has opened between the compensation of the average American worker and her/his average labor productivity.

The fact that the relationship between wages and productivity has been severed in recent decades presents a fundamental problem, both for U.S. capitalism and for mainstream economic theory. It calls into question the presumption of “just deserts” within U.S. economic institutions as well as within the theory of distribution created and disseminated by mainstream economists.

It means, in short, that much of what American workers are produced is not being distributed to them, but instead is being captured to their employers and wealthy individuals at the top, and that mainstream economic theory operates to obscure this growing problem.

It should therefore come as no surprise that Summers and Stansbury, while admitting the growing wage-productivity gap, will do whatever they can to save both current economic institutions and mainstream economic theory.

First, Summers and Stansbury conjure up a conceptual distinction between a “delinkage view,” according to which increases in productivity growth no long systematically translate into additional growth in workers’ compensation, and a “linkage view,” such that productivity growth does not translate into pay, but only because “other factors have been putting downward pressure on workers’ compensation even as productivity growth has been acting to lift it.” The latter—linkage—view maintains mainstream economists’ theory that wages correspond to workers’ productivity and that, in terms of the economy system, increasing productivity will raise workers’ wages.

Second, Summers and Stansbury compare changes in labor productivity and various time-dependent and lagged measures of the typical worker’s compensation—average compensation, median compensation, and the compensation of production and nonsupervisory workers—and find that, while compensation consistently grows more slowly than productivity since the 1970s, the series (both of them in log form) move largely together.

Their conclusion, not surprisingly, is that there is considerable evidence supporting the “linkage” view, according to which productivity growth is translated into increases in workers’ compensation and hence improving living standards throughout the postwar period. Thus, in their view, it’s not necessary—and perhaps even counter-productive—to shift attention from growth to solving the problem of inequality.

ButSummers and Stansbury are still unable to dismiss the existence of an increasing wedge between productivity and compensation, which has two components: mean and median labor compensation have diverged and, at the same time, there’s been a falling labor share in the United States.

That’s where they stumble. They look for, but can’t find, a link between productivity and those two measures of growing inequality. There simply isn’t one.

What there is is a growing gap between productivity and compensation in recent decades, which has result in both a falling labor share and higher growth of labor compensation at the top. That is, more surplus is being extracted from workers and some of that surplus is in turn distributed to those at the top (e.g., industrial CEOs and financial executives).

Moreover, one can argue, in a manner not even envisioned by Summers and Stansbury, that the increasing gap between productivity and workers’ compensation is at least in part responsible for the productivity slowdown. Changes in the U.S. economy that emphasize capturing an increasing share of the surplus from around the world have translated into slower productivity growth in the United States.

The only conclusion, contra Summers and Stansbury, is that even if productivity growth accelerates, there is no evidence that suggests “the likely impact will be increased pay growth for the typical worker.”

More likely, at least for the foreseeable future, is the increasing inequality and the (relative) immiseration of American workers. Those are the problems neither existing economic institutions nor mainstream economic theory are prepared to acknowledge or solve.

*Actually, the argument is about productivity and compensation, not wages. In fact, Summers and Stansbury assert that “the definition of ‘compensation’ should incorporate both wages and non-wage benefits such as health insurance.” Their view is that, since the share of compensation provided in non-wage benefits significantly rose over the postwar period, comparing productivity against wages alone exaggerates the divergence between pay and productivity. An alternative approach distinguishes what employers have to pay to workers, wages (the value of labor power, in the Marxian tradition), from what employers have to pay to others, such as health insurance companies, in the form of non-wage benefits (which, again in the Marxian tradition, is a distribution of surplus-value).