From David Ruccio Most of us pay the taxes we’re required to pay. That’s because there aren’t many ways to avoid them. Sales, property, payroll, or income—the tax is paid at the time of the purchase, the amount is deducted from our paychecks, or the records go directly to the government. There’s no real way around them. And we pay those taxes out of wages and salaries more or less willingly, since that’s how government services are financed. Not so for those who are able to capture the surplus. Large corporations and wealthy individuals pay far less than their fair share of taxes. Their ability to evade taxes is only matched by their insistent demand that their tax rates be lowered even more. We’ve known for a long time that large corporations use a variety of mechanisms—from claiming

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Most of us pay the taxes we’re required to pay. That’s because there aren’t many ways to avoid them. Sales, property, payroll, or income—the tax is paid at the time of the purchase, the amount is deducted from our paychecks, or the records go directly to the government. There’s no real way around them. And we pay those taxes out of wages and salaries more or less willingly, since that’s how government services are financed.

Not so for those who are able to capture the surplus. Large corporations and wealthy individuals pay far less than their fair share of taxes. Their ability to evade taxes is only matched by their insistent demand that their tax rates be lowered even more.

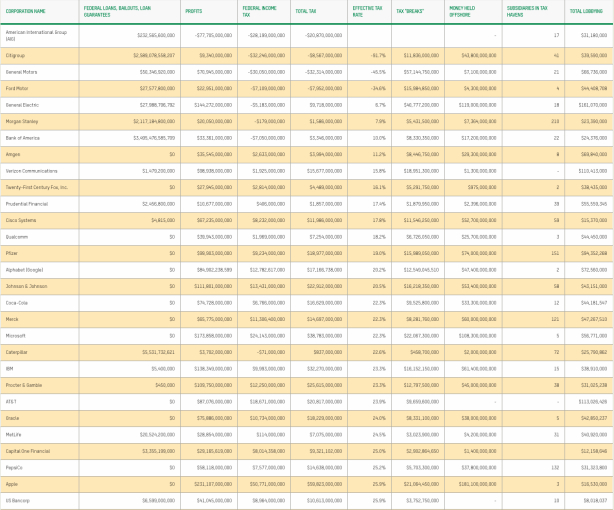

We’ve known for a long time that large corporations use a variety of mechanisms—from claiming tax deductions and using loopholes to stashing profits in tax havens abroad—to lower their effective tax burden.

Thus, for example, according to Oxfam America (pdf), between 2008 to 2014, the top 50 companies in the United States paid an effective tax rate (to the federal government as well as to states, localities, and foreign governments) of just 26.5 percent overall, 8.5 percent points lower than the statutory rate of 35 percent and just under the average of 27.7 percent paid by other developed countries. And then they use their tax savings to lobby for even more tax advantages.

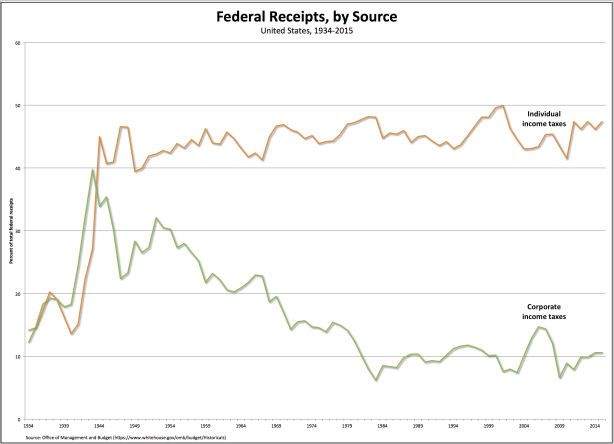

One of the results of corporate tax evasion is, I’ve argued before, the tax burden has been shifted from corporations to individuals.

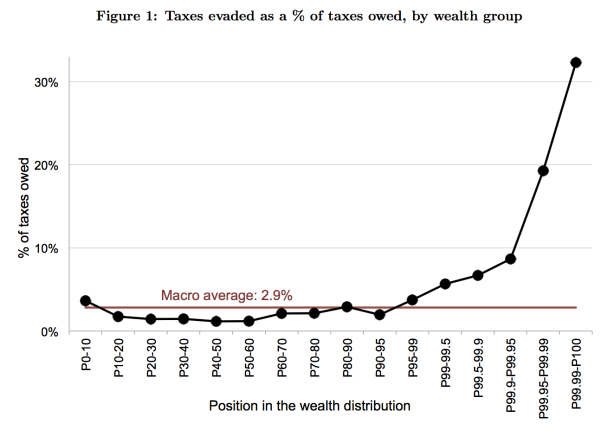

But not to wealthy individuals. As new research by Annette Alstadsaeter, Niels Johannsen, and Gabriel Zucman has shown (pdf), the top 0.01 percent of the wealth distribution—a group that includes households with more than $40 million in net wealth—evades about 30 percent of its personal income and wealth taxes. This is an order of magnitude more than the average evasion rate of about 3 percent.

The main reason those at the very top of the wealth distribution are able to evade a large portion of their tax burden is because they’ve managed to use their cut of the surplus to accumulate personal wealth—and then to hide that wealth offshore.

Ownership of wealth is, of course, extremely concentrated. Offshore wealth even more so. According to Alstadsaeter et al., the top 0.01 percent of the distribution owns about 50 percent of offshore wealth, which means the top 0.01 percent manage to hide about one quarter of their true wealth.

We now have an economy in which more and more surplus is captured by a small number of large corporations and wealth individuals, who in turn manage to evade a larger and larger portion of their fair share of taxes by hiding the surplus.

Oxfam’s view is that

Rather than engaging in a mutually destructive race to the bottom, the US should stake out a leadership role in addressing structural problems in the global tax system. The US should push for a truly inclusive process where all governments are able to build mutually beneficial tax rules that improve information sharing, transparency and accountability globally.

Until that happens, the rest of us—who are not members of the boards of directors of large corporations or wealthy individuals—will continue to be forced to shoulder the burden of paying taxes to finance government services. And the distribution of income and wealth will become, year by year, increasingly unequal.