From David Ruccio When I ask my students that question, they don’t really have an answer. That’s because, like much of the rest of the U.S. population, they don’t have much experience with unions, either directly or indirectly—not when the union membership rate has fallen to below 11 percent nationwide and is only 6.4 percent in the private sector. And if you pose that question to neoclassical economists, the response is: labor unions cause unemployment, by setting a wage rate that exceeds the equilibrium price for labor. According to the neoclassical story, while union workers (“insiders”) may benefit, unemployed non-union workers (“outsiders”) lose out. So, their overall conclusion is, unions ultimately hurt workers and cause increased inequality. Unions should therefore be

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

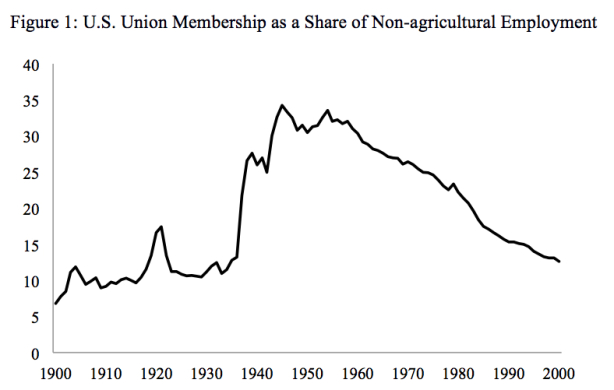

When I ask my students that question, they don’t really have an answer. That’s because, like much of the rest of the U.S. population, they don’t have much experience with unions, either directly or indirectly—not when the union membership rate has fallen to below 11 percent nationwide and is only 6.4 percent in the private sector.

And if you pose that question to neoclassical economists, the response is: labor unions cause unemployment, by setting a wage rate that exceeds the equilibrium price for labor. According to the neoclassical story,

while union workers (“insiders”) may benefit, unemployed non-union workers (“outsiders”) lose out. So, their overall conclusion is, unions ultimately hurt workers and cause increased inequality. Unions should therefore be discouraged.

For my students who have taken a course in mainstream economics, that’s pretty much the only answer that will be offered to them.*

But what if we look back to the heyday of unions—to the period that begins during the first Great Depression (when the Wagner Act was passed and unionization rates once again began to rise) and extends through the 1950s?

According to a new study by Brantly Callaway and William J. Collins, who utilize a novel dataset compiled from archival records of a survey of male workers in five non-Southern cities conducted in 1951, unions played an important role in reducing inequality, especially at the bottom of the wage scale.

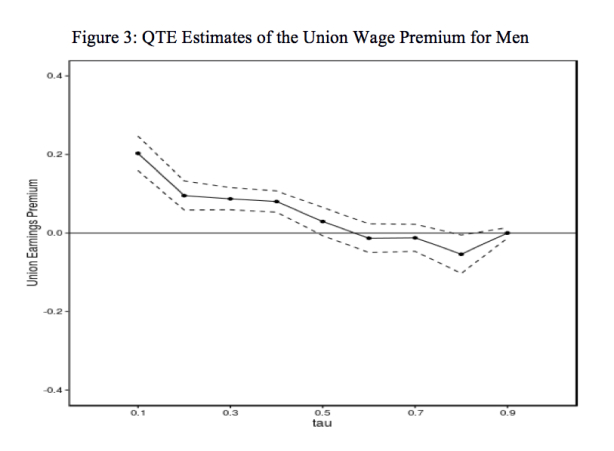

Thus, for example, at the 10th percentile, union workers earned 20.3 log points more than comparable non-union workers—while the difference at the median was smaller and, at the 80th, the difference turns negative.

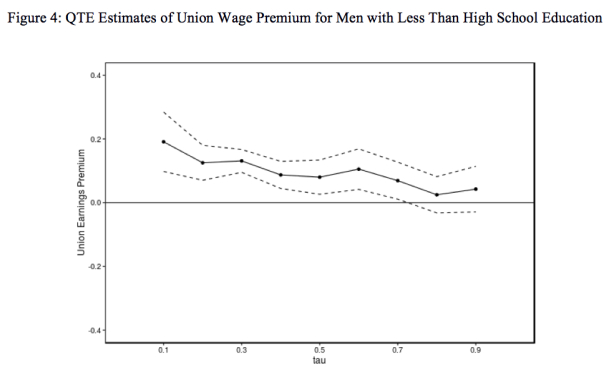

For less-educated workers (those with less than a high-school education), the premium at the bottom was similar (at 19.1 log points) but the advantage persisted across all percentiles. And the union wage premium was relatively large, and it remained so, throughout the Black income distribution. The clear indication is that the emergence of industrial unions after 1935, which sought to unionize production workers along industry rather than craft lines, opened more better-paying union job opportunities for both less-educated and Black workers.

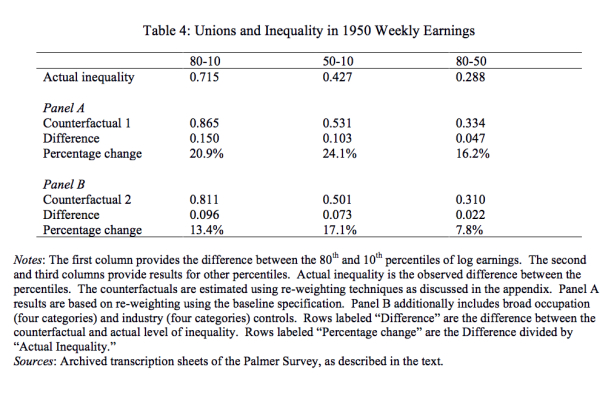

Callaway and Collins also conduct some counterfactual estimations concerning wage inequality, by looking at what would happen if union workers had been paid according to the non-union wage schedule. Their Table 4 (Panel A), shows that in terms of all measures—overall inequality (the difference between the 80th percentile and the 10th percentile), lower-tail inequality (the difference between the 50th percentile and the 10th percentile), and upper-tail inequality (the difference between the 80th percentile and 50th percentile)—inequality is significantly higher in the counterfactual “no union” scenario than in reality. In other words, the overall wage distribution was considerably narrower in 1950 than it would have been if union members had been paid like non-union members with similar characteristics.

As I see it, there are two lessons that can be drawn from the Callaway and Collins study. First, in terms of U.S. history, unions played a significant role in mitigating the effects of competition among workers, both raising workers’ wages and reducing inequality among workers. Second, with respect to economic theory, their research shows that simple supply-and-demand stories (which neoclassical economists use to attempt to explain inequality in terms of skills and levels of education) are profoundly misleading precisely because they leave out institutions.

One of the most important institutions in the postwar period in the United States, when economic inequality was much lower than today, were labor unions.

*If students were exposed to something other than neoclassical economics, they’d learn that unions do many other things, including helping non-union workers, through: (1) the threat of unionization (nonunion employers worried about a possible unionization drive may match union pay scales to reduce the demand for organization), (2) the ripple effect (like minimum-wage increases, union wage rates for production workers can lead to increases in wages for those above them, e.g., their managers), and (3) the moral economy (unions help institute norms of fairness regarding pay, benefits, and worker treatment that can extend beyond the unionized core of the workforce). They might also learn that, historically and by examining the experience in other countries, unions have often defended and promoted the larger interests of workers—in their enterprises (by demanding a say in decisions about such things as safety and jobs), nationally (by contributing time and money to political parties and campaigns), and internationally (by cooperating with and assisting unionization efforts in other countries).