From David Ruccio [ht: ja] describes the arrival of the first robots at Tenere Inc. in Dresser, Wisconsin: The workers of the first shift had just finished their morning cigarettes and settled into place when one last car pulled into the factory parking lot, driving past an American flag and a “now hiring” sign. Out came two men, who opened up the trunk, and then out came four cardboard boxes labeled “fragile.” “We’ve got the robots,” one of the men said. They watched as a forklift hoisted the boxes into the air and followed the forklift into a building where a row of old mechanical presses shook the concrete floor. The forklift honked and carried the boxes past workers in steel-toed boots and earplugs. It rounded a bend and arrived at the other corner of the building, at the end of

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

[ht: ja] describes the arrival of the first robots at Tenere Inc. in Dresser, Wisconsin:

T

he workers of the first shift had just finished their morning cigarettes and settled into place when one last car pulled into the factory parking lot, driving past an American flag and a “now hiring” sign. Out came two men, who opened up the trunk, and then out came four cardboard boxes labeled “fragile.”

“We’ve got the robots,” one of the men said.

They watched as a forklift hoisted the boxes into the air and followed the forklift into a building where a row of old mechanical presses shook the concrete floor. The forklift honked and carried the boxes past workers in steel-toed boots and earplugs. It rounded a bend and arrived at the other corner of the building, at the end of an assembly line.

The line was intended for 12 workers, but two were no-shows. One had just been jailed for drug possession and violating probation. Three other spots were empty because the company hadn’t found anybody to do the work. That left six people on the line jumping from spot to spot, snapping parts into place and building metal containers by hand, too busy to look up as the forklift now came to a stop beside them.

Tenere is just one of many factories and offices in which employers, in the United States and around the world, are installing robots and other forms of automation in order to boost their profits.

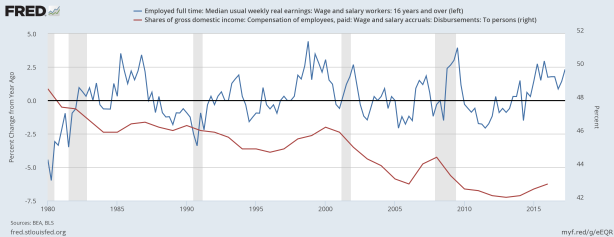

They’re not doing it because there’s any kind of labor shortage. If there were, wages would be rising—and they’re not. Real weekly earnings for full-time workers (the blue line in the chart) increased only 2.3 percent on an annual basis in the most recent quarter. Sure, they complain about a shortage of skilled workers but employers clearly aren’t being compelled to raise wages to attract new workers. As a result, the wage share in the United States (the red line) continues to decline on a long-term basis, falling from 51.5 percent in 1970 to 43 percent last year (only slightly higher than it was, at 42.2 percent, in 2013).

No, they’re using robots in order to compete with other businesses in their industry, by boosting the productivity of their own workers to undercut their competition and capture additional surplus-value.

And they can do so because robots have become much more affordable:

No longer did machines require six-figure investments; they could be purchased for $30,000, or even leased at an hourly rate. As a result, a new generation of robots was winding up on the floors of small- and medium-size companies that had previously depended only on the workers who lived just beyond their doors. Companies now could pick between two versions of the American worker — humans and robots. And at Tenere Inc., where 132 jobs were unfilled on the week the robots arrived, the balance was beginning to shift.

So, where does that leave us?

The prevalent response has been to worry about mass unemployment. However, as I explained a month ago, I don’t think that’s the issue, at least at the macro level.

If workers are displaced from their jobs in one plant or sector, they can’t just remain unemployed. They have to find jobs elsewhere, often at lower wages than their earned before. That’s how capitalism works.

Much the same holds for workers who don’t lose their jobs but who, as new technologies are adopted by their employers, are deskilled and otherwise become appendages of the new machines. They can’t just quit. They remain on the job, even as their working conditions deteriorate and the value of their ability to work falls—and their employers’ profits rise.

No, the real problem is how the gains from the introduction of robots and other new technologies are being unevenly distributed.

And that’s an old problem, which was confronted by forces as diverse as the Luddites and the John L. Lewis-led United Mineworkers of America, none of which was opposed to the use of new, labor-saving technologies.

In fact, Lewis’s argument was that machinery should replace hand work in the mines, which would serve to both ease the burden of miners’ work increase their wages—all under the watchful eye of their union. And mine-owners who attempted to pay workers less, without technological improvements, should be driven out of business.

Mr. Lewis called upon the miners to accept machinery, since they could not turn back the clock, but to demand a fair share of the benefits of mechanization in the form of shorter hours and increased compensation. He said that machines must be made the workingman’s ally, and that nothing was to be gained by fighting them.

The fact is, right now workers are not getting “a fair share of the benefits of mechanization,” whether in the form of shorter hours or increased compensation.

And if employers are not willing to provide those benefits, workers themselves should be given a say in what kinds of robots and other new technologies will be introduced, what their working hours will be, and how much they will be compensated.

Only then will workers be able to confidently say, “we’ve got the robots.”