According to the accepted narrative after about 1950 female participation rates started to rise thanks to inventions like the washing machine and kept rising forever after. Reality is more confusing. According to a recent book by Julia Sophie Wörsdorfer, washing machines were, contrary to the ideas of Ha-Joon Chang, not that important. Neither cross sectional data nor time series analysis yields a strong correlation between ownership of a washing machine and high female labour force participation. But there is a strong link between the rise of the washing machine and a rise of public and personal cleanliness standards – more kinds of clothes were washed more often than before in less time. The Japanese data also contradict the washing machine thesis. It explains neither the post 1960

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

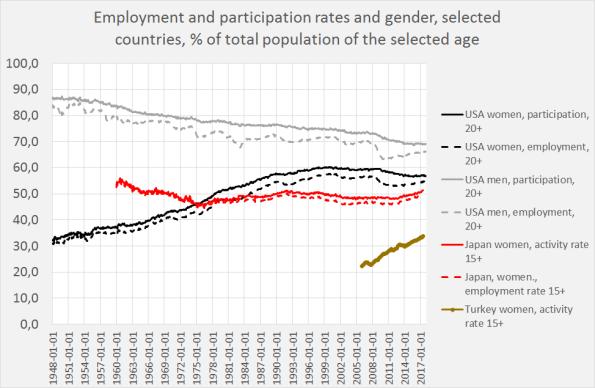

According to the accepted narrative after about 1950 female participation rates started to rise thanks to inventions like the washing machine and kept rising forever after. Reality is more confusing. According to a recent book by Julia Sophie Wörsdorfer, washing machines were, contrary to the ideas of Ha-Joon Chang, not that important. Neither cross sectional data nor time series analysis yields a strong correlation between ownership of a washing machine and high female labour force participation. But there is a strong link between the rise of the washing machine and a rise of public and personal cleanliness standards – more kinds of clothes were washed more often than before in less time. The Japanese data also contradict the washing machine thesis. It explains neither the post 1960 decline of the female Japanese participation rate nor the recent increase in Japan or, for that matter, Turkey. Clearly, the female participation rate is to quite an extent a cultural phenomenon, though it is no doubt also influenced by education, fertility decisions and urbanization. The idea that the washing machine enabled women to emulate men is, however, wrong. They made and make their own choices, often more family oriented than those of men. Which is not necessarily a bad thing.

The data shown here are complicated. They are corrected for seasonal influences. In Japan in the sixties, seasonal fluctuation were much larger than nowadays, which means that the series shown here underestimates the participation decline in the sixties. The series are also influenced by demographics. Male as well as female participation above 55 years of age is considerably lower than below 55. This is rapidly changing but even then the greying of societies tends to lower average participation – which makes the Japanese increase more remarkable. The decline of the USA male participation rate is not just demographic but also visible for the 25-54 group. Between 1960 and 2016 this rate declined from about 97% to around 88% but seems to have stabilized after 2016.