A variable like GDP (Gross domestic Product) receives a lot of flack from economists. Much of this is misguided. The economists should not look at GDP but at the national accounts (of which GDP is one, but only one, variable). And they should not criticize the accounts but praise them. A 2016 ECB working paper about the flagship ECB ‘EAGLE-FLI’ neoclassical macro-model (Bokan e.a. (2016)) shows why: neoclassical have no idea about how and what to measure. National account statisticians do. According to the abstract of the ECB paper new features of the EAGLE-FLI model were the inclusion of ‘deposits’ and banks. Bokan e.a. go on to state: ‘banks collect deposits from domestic households’. Auch Banks don’t collect deposits. As they can’t collect what they already have. At least, the

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

A variable like GDP (Gross domestic Product) receives a lot of flack from economists. Much of this is misguided. The economists should not look at GDP but at the national accounts (of which GDP is one, but only one, variable). And they should not criticize the accounts but praise them. A 2016 ECB working paper about the flagship ECB ‘EAGLE-FLI’ neoclassical macro-model (Bokan e.a. (2016)) shows why: neoclassical have no idea about how and what to measure. National account statisticians do.

According to the abstract of the ECB paper new features of the EAGLE-FLI model were the inclusion of ‘deposits’ and banks. Bokan e.a. go on to state: ‘banks collect deposits from domestic households’.

Auch

Banks don’t collect deposits. As they can’t collect what they already have. At least, the ‘deposit taking institutions’ which are generally known as banks don’t. They create the stuff. And not just according to ‘heterodox’ economists. But also according to the statisticians which measure this.

According to the definition used by statisticians deposits are by definition a liability of a bank. They can be transferred from one bank to another bank. And though they can leave a country they do not leave the wider banking system (institutional detail differs a bit between countries). There are no real of digital wallets filled with ‘deposits’ in the vaults of households. There is nothing to be gathered from households. There might be vaults filled with cash. But this is not what Bokan e.a. are writing about. They state (again: this is about the flagship ECB model): “In line with these contributions [i.e. other DSGE models, M.K.], we assume a cashless economy, so there is no explicit role for money” (Bokan e.a. (2013) footnote 4) and: “The model represents a cashless economy (see Woodford, 1998) so we abstract from money and, hence, from interbank liquidity as well” (p. 8) and “we allow deposits to endogenously adjust consistently with the bank’s balance sheet. This calibration strategy emphasizes the role of bank’s loans and thus induces a broad interpretation of bank deposits”(p. 22).

Wow.

Clearly, deposits are not cash and deposits are not ‘money’. Don’t ask. Or at least, don’t ask me. As we all know, cash still is an important kind of money. Also, statisticians use a concept of money which (consistent with textbooks of economics, by the way) includes cash as well as some deposits (long-term savings deposits are excluded). To be scientifically consistent one should, when one for the first time introduces ‘deposits’ into a model, use the prevalent terminology. Biologists do, when they use the latin name of an organism. Psychologists do when they use the official name of a disorder. Chemists do when they use the name of a compound. Physicists do (the periodic table!) Geologists do. Economic statisticians do. Neoclassical economist – don’t. Or at least: Bokan e.a. don’t.

Also, the statement that deposits adjust consistent with the bank’s balance sheets confuses the mind. Deposits are defined as an element of bank’s balance sheets (i.e. a liability of banks). Banks can do nothing else than letting their balance sheets adjust with deposits. And banks do not gather deposits from households: credit agreements between a bank and a household (or a company) lead to the creation of deposit money. As an example: when a consumer uses his or her credit card to buy something the consumer incurs a debt towards the bank which issued the credit card. This debt enables the bank, considering the legal and institutional structure of our economies, to transfer new deposits (backed by the promise of the buyer to pay the debt down – with other deposits or with cash) to the account of the seller. Even if the account of the seller is at another bank the deposits stay within the banking sector (technically, one should also take account of consumers which change deposits for cash but Bokan e.a. assume cash away).

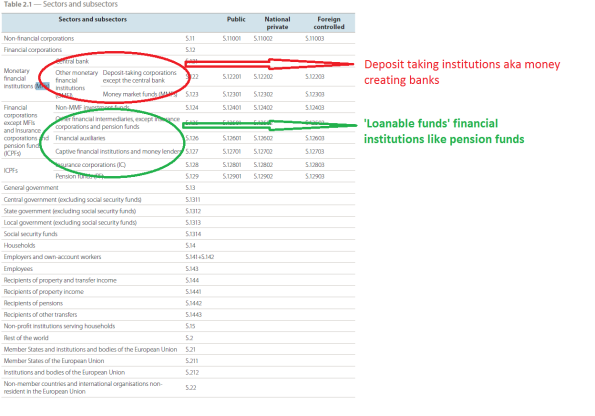

What Bokan e.a. in fact do is assuming money creating banks (sector S 122 in the ESA 2010) away (though somehow these ‘deposit taking institutions’ do seem to increase the amount of deposits in a mysterious way when the economy grows though I have to admit that I do not fully understand the sentence about this quoted above) and to assume that all lending in an economy occurs via financial institutions like pension funds (or sectors S 124-S 128 in the ESA 2010).

Come in the national accounts. The accounts precisely define and measure the (sub-)sectors of the economy and especially for the financial sector the aggregate of all the transactions and balance sheet positions is precisely known (as of the third quarter of 2017 pension fund deposits were, according to De Nederlandse Bank, 26 billion euro or 1,9% of the total value of assets of Dutch pension funds, rather trifling compared with the 420 billion of different kind of deposits (not all of the included in the ‘M3’ definition of money) owned by Dutch households according to the Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek). Below, from the European System of Accounts 2010, the exact delineations which enable us to show which sectors are left out by Bokan e.a. The statisticians do a very good job measuring the stocks and flow. Bokan e.a. do a bad job using this data and these definitions. Aside: as Bokan e.a. introduce a class of entrepreneurs which owns all the capital and households which have nothing to sell but their labor their model might be called classical instead of neoclassical. It should be possible to turn it into a Marxist model by assuming that wages are set including a mark down representing market power of the entrepreneurs and some kind of underconsumption mechanism caused by an outflow of this rent income of the entrepreneurs from the flow economy towards ‘abroad’. That would be fun. But as long as the sectors are not well-defined, it would be as unscientific as the model as it is. Maybe I just misunderstood Bokan e.a. but in that case they should have written it down more clearly. Much more clearly.