S Source (p. 32) Oops. Mark Gertler (with Kiyotaki and Prestipino) does it again: “There has been considerable progress in developing macroeconomic models of banking crises. However, most of this literature focuses on the retail sector where banks obtain deposits from households.” After ‘obtaining’ deposits, these banks are supposed to lend the ‘money’ to households and companies. Source: the 2000+ pages Handbook of [neoclassical, M.K.] Macroeconomics edited by John Taylor. As we know, this is not true. In reality, ‘loans create deposits’. A joint act of lender and borrower, in my 1975 Dutch textbook this was called ‘wederzijdse schuldaanvaarding’ or ‘mutual acceptance of debt’. The lender has a liability towards the borrower (the deposits on the account have to be freely available to

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

S

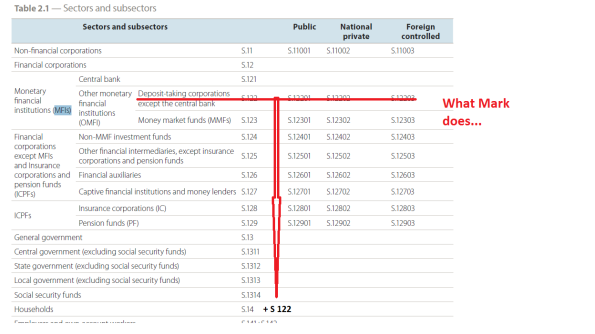

Oops. Mark Gertler (with Kiyotaki and Prestipino) does it again: “There has been considerable progress in developing macroeconomic models of banking crises. However, most of this literature focuses on the retail sector where banks obtain deposits from households.” After ‘obtaining’ deposits, these banks are supposed to lend the ‘money’ to households and companies. Source: the 2000+ pages Handbook of [neoclassical, M.K.] Macroeconomics edited by John Taylor. As we know, this is not true. In reality, ‘loans create deposits’. A joint act of lender and borrower, in my 1975 Dutch textbook this was called ‘wederzijdse schuldaanvaarding’ or ‘mutual acceptance of debt’. The lender has a liability towards the borrower (the deposits on the account have to be freely available to the borrower) and the borrower promises to pay back the debt which created these deposits. They can be transmitted from one bank to another. That’s the whole point of the system: in a currency zone bank A accepts deposits created by bank B as means of exchange which at a 1:1 exchange rate can be used to pay down a debt owed by a person to bank A. And the government accepts the deposits at a 1:1 exchange for tax debts. Neat. But these deposits are not somewhere in a vault of a household to a bank. Alas, after about 1980 Anglo-Saxon textbooks started to take over the Dutch market.

Insurance companies and Pension funds obtain deposits (but generally do not lend these but invest them in existing Italian government bonds or other financial assets). What Gertler e.a. in fact do is to assume that the entire money creating banking system (excluding the central bank) is part of the sector households. But in that case, households would be involved in money creating loans to companies. Or the government. Which, in the models, does not seem happen (at least not in an explicit way).

Wouldn’t it be nice and also a hallmark of science if the neoclassical modellers just stuck with the institutional setup of the economy as laid out by the statisticians. My 1975 textbook as consistent with the statistical measurements. Anlo-Saxon textbooks still aren’t – a lack of institutional precision which makes for inconsistent and incoherent models. To take the ‘the map and the territory’ metaphore: yes, a map has to be abstract and I do use a highly abstract map of French highways to get to from my home to the Drome department. But that’s still a map of the territory. I do not use a map of the moon.