@Brankomilan leads us to this (french) piece about Austria. It states that the Austrian government enacted a new law which authorizes working days of 12 hours and working weeks of 60 hours. A). This is a clear case of retrogression. It’s good to read what, in 1921, the International Labor Office stated in its first annual report: ““It would therefore be almost impossible to exaggerate the truly revolutionary character of the events which during the last years of the war or after the war took place in the sphere of the regulation of hours of work…. During the years 1918-19 the 8-hour day has, either by collective agreements or by law, become a reality in the majority of industrial countries … Before the war, whenever even a minimum or gradual reduction of the working day was proposed,

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

@Brankomilan leads us to this (french) piece about Austria. It states that the Austrian government enacted a new law which authorizes working days of 12 hours and working weeks of 60 hours.

A). This is a clear case of retrogression. It’s good to read what, in 1921, the International Labor Office stated in its first annual report:

““It would therefore be almost impossible to exaggerate the truly revolutionary character of the events which during the last years of the war or after the war took place in the sphere of the regulation of hours of work…. During the years 1918-19 the 8-hour day has, either by collective agreements or by law, become a reality in the majority of industrial countries … Before the war, whenever even a minimum or gradual reduction of the working day was proposed, foreign competition was one of the arguments employed in the universal controversy concerning the working day”

Six days of eight hours make 48 hours a week… Note the phrase about ‘foreign competition’. In ‘Globalists‘ Quinn Slobodian notes how in the twenties people like Mises and Hayek raged, raged about the importance of international competition to keep labor in check and to make people work more for lower wages. Mind that Slobodian notes that Von Mises as well as Von Hayek were quite ‘nostalgic’ (my phrase) for the Austrian-Hungarian multicultural world they had lost and which, by enabling academic and bureaucratic careers, had been so good for their lesser gentry families. Fun fact: until economic statistics turned out to show that shared prosperity was not just possible but also a ‘New Deal’ reality, Mises and Hayek were very enarmored by the rapidly expanding science of economic measurement.

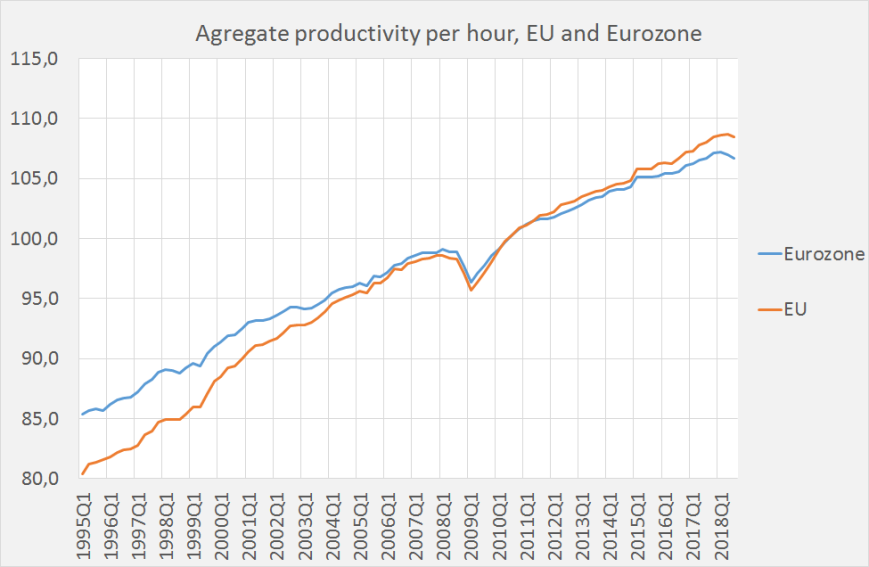

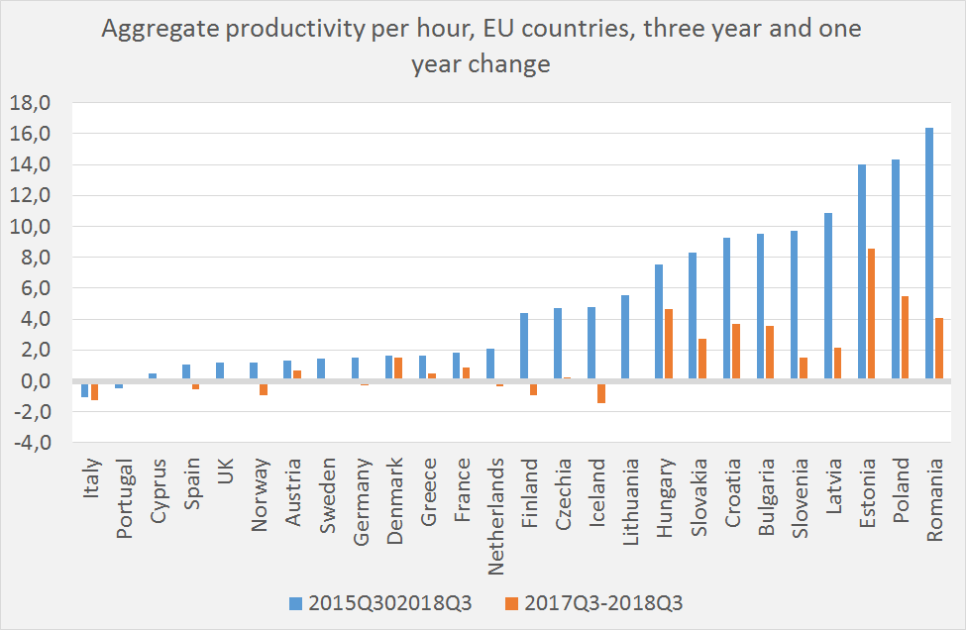

B. One of the most important result of economic measurement is that it shows how much productivity has risen. We need much fewer people and hours to produce economic items than we used to do. And productivity continues to increase, even when the third quarter of 2018 shows a cyclical setback for the Eurozone (second graph). Increases of 1% a year are totally possible and some EU countries even show increases of 4 to 5% per year. Instead of dumbing down and controlling labor, like the Austrians do, we have to unleash labor and to raise productivity. The Amazone robots are a good thing. This, of course, requires full employment policies from the government. One element of these policies is a shorter work week. Not a longer one. The Austrian 60 hour work week is not just a capitulation for big business or fear of the increasing number of old people. It’s worse. It’s bad economics which somehow, for some reason, has the idea that dumbing down labor instead of treating people with dignity and unleashing their creativity should be a moral prerogative of the economic order. We do not need 60 hour a week workweeks to counter a greying society, we need robots. And not necessarily robots which care for the old, but robots which perform stupid menial tasks like menial work in warehouses which will enable people to do better work.

Yes, there are reasons why productivity in Poland is increasing at a break neck speed while it’s lower in Germany and the Netherlands. Unemployment in Germany and the Netherland is however getting lowish, which (mind my words) will cause an increase of productivity, if not by the introduction of more and better robots then by people moving out of crappy jobs to better, jobs which pay more. Down with Deliveroo, up with pay for elementary school teachers.