I’ve always been wondering why small farmers enjoying ‘Fair Trade’ privileges are not modernizing faster in the sense that they invest and modernize, capture the market and do not need ‘us’ anymore. Yes, I know that many international trade rules are not exactly fair. And the words ‘Banana republic’ and ‘Banana wars‘ come from somewhere – the official phrase for such ‘politically enforced’ global value systems is ‘empire‘ (TTIP anyone?). But even then – why do many small farmers and even slaves (cocoa production!) in more or less stable countries still need western NGO’s and benevolent consumers and companies like Chocolonely? There are reasons for this – as it surely is possible that, when circumstances are ‘right’, development can be very fast. My ideas about this were influenced by

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

I’ve always been wondering why small farmers enjoying ‘Fair Trade’ privileges are not modernizing faster in the sense that they invest and modernize, capture the market and do not need ‘us’ anymore. Yes, I know that many international trade rules are not exactly fair. And the words ‘Banana republic’ and ‘Banana wars‘ come from somewhere – the official phrase for such ‘politically enforced’ global value systems is ‘empire‘ (TTIP anyone?). But even then – why do many small farmers and even slaves (cocoa production!) in more or less stable countries still need western NGO’s and benevolent consumers and companies like Chocolonely? There are reasons for this – as it surely is possible that, when circumstances are ‘right’, development can be very fast. My ideas about this were influenced by my Ph. D. about Dutch agriculture. Between about 1890 and 1910 Dutch farmers managed to change input, output and credit markets in a fundamental way by establishing literally thousands of local cooperative purchasing, selling, production and saving and credit cooperatives while they also invested in new production systems; the government did its part by establishing an (grass roots) education and (grass roots) research system. Also, the Netherlands were in those days basically a low corruption, high trust society while the government (but also local dairy factories and railway entrepreneurs) enhanced basic education and roads and railways. On top of this, local teachers and other well-educated elite often did a very good job as voluntary secretaries or accountants of the boards of the cooperatives. Everything was ‘right’. And change did happen.

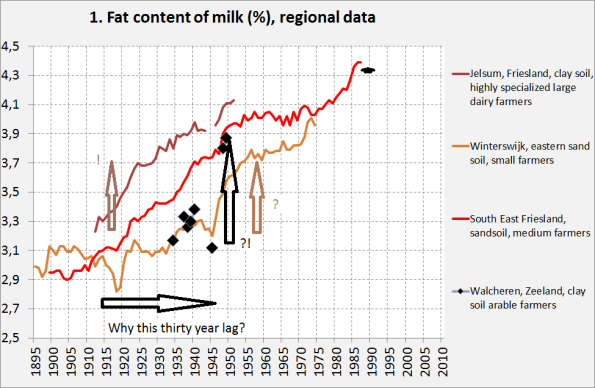

Or, did it? I recently delved into the archives of dairy factories and related organizations. Long story short: specialized dairy farmers in Friesland were able the work together with the government, scientists, veterinarians and the new cooperative and private dairy factories to change all kind of institutions which hampered modernization. Bovine tuberculosis was tackled (also because Frisian dairy cattle was an export product), factories were established and improved and meticulous ‘Taylorist’ measurement and accounting enabled farmers to increase fat content of the milk of their cows (a highly inheritable trait). Remarkably, farmers in the East and in Zeeland (the South West) did not follow suite, not even when dairy factories were established. It took the government to change institutions and price incentives and to establish systems to share costs of public services like the eradication of bovine tuberculosis. A small but telling example: around 1910, Frisian dairy factories already fined farmers which still used wooden buckets (breeding grounds for bacteria) instead of seamless metal buckets – but it was only in the thirties that the government outlawed (and controlled!) the use of wooden buckets in the consumption milk areas around the cities in Holland. The incentive of the factories was the need to produce ‘export quality’ butter and cheese. The incentive of the government was the growing perception that aspects of public health could and should be managed more actively by the government – a development based upon medical progress but which was decisevely influenced by the introduction of general voting rights in 1919.

Another and less benevolent example is Walcheren in Zeeland. To disable the German army to shell allied ships going to the port of Antwerp via the Scheldt estuary, the allied armies inundated Walcheren, a Dutch polder on the borders of the Scheldt estuary. Among other things this led to the annihilation of the entire stock of bovine. Restocking the area with cattle from Friesland led to a sudden jump in fat content of milk. For some reason and despite the best efforts of the Walcheren dairy factory, in the thirties Walcheren farmers had not been able to work together to buy a cheap second class Frisian breeding bulls – which would have enabled a serious improvement of their animals (aside of fat, a sturdy constitution was an important element of cattle breeding in Friesland).

The point: only in rare circumstances, everything is ‘right’ and civil society will itself change its institutional set up. In other circumstances, the government has to step in – but aside from radical democracy there is no guarantee that it will do so in an effective and just way. But the small farmers won’t get anywhere without an effective government. See also Niek Koning about this.