From David Ruccio 50 years ago, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, just days after joining a march of thousands of African-American protestors down Beale Street, one of the major commercial thoroughfares in Memphis, Tennessee. King and the other marchers were demonstrating their support for 1300 striking sanitation workers, many of whom held placards that proclaimed, “Union Justice Now!” and “I Am a Man.” The night before his assassination, King told the striking sanitation workers and those who supported them: “We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through.” He believed the struggle in Memphis exposed the need for economic equality, social justice, and human dignity

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

50 years ago, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, just days after joining a march of thousands of African-American protestors down Beale Street, one of the major commercial thoroughfares in Memphis, Tennessee. King and the other marchers were demonstrating their support for 1300 striking sanitation workers, many of whom held placards that proclaimed, “Union Justice Now!” and “I Am a Man.”

The night before his assassination, King told the striking sanitation workers and those who supported them: “We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through.” He believed the struggle in Memphis exposed the need for economic equality, social justice, and human dignity that he hoped the Poor People’s Campaign would highlight nationally.

The struggle hasn’t ended—nor have the conditions that provoked the Campaign in the first place.

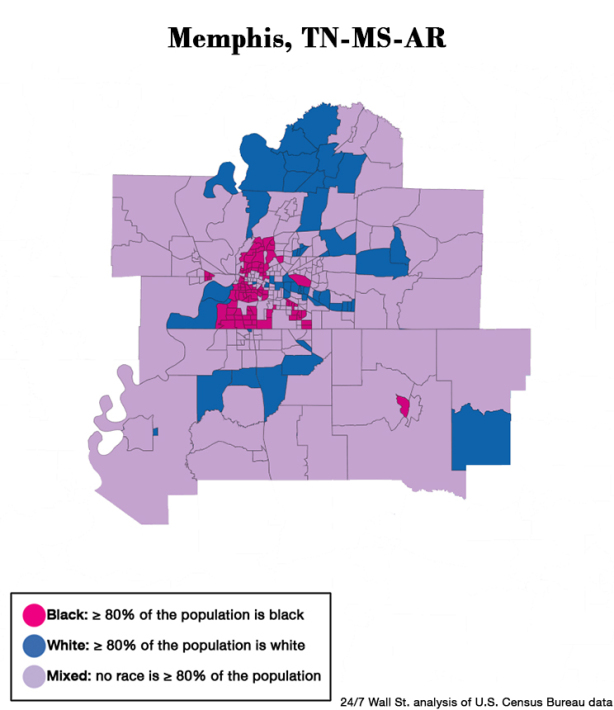

Today, according to an analysis by 24/7 Wall St., Memphis is the fourth most segregated city in the United States—following only Detroit, Chicago, and Jackson, Mississippi. Just 2.3 percent of white Memphis residents live in neighborhoods where are least 40 percent of the population are poor, compared to 20.5 percent of the black population.

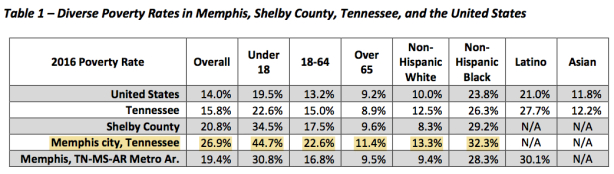

Moreover, data collected by Elena Delavega (pdf) of the Department of Social Work at the University of Memphis show the city to have an overall poverty rate of 26.9 percent—32.3 percent for blacks and 44.7 for children. In 2016, Memphis reverted to being the poorest Metropolitan Statistical Area with a population over a million people.

As recently as last year, the local Chamber of Commerce noted that Memphis offers a “work force at wage rates that are lower than most other parts of the country.”

King understood well the connection between poverty and capitalism. The year before his death, on 31 August 1967, he delivered “The Three Evils of Society” speech at the first and only National Conference on New Politics in Chicago.

When we foolishly maximize the minimum and minimize the maximum we sign the warrant for our own day of doom.It is this moral lag in our thing-oriented society that blinds us to the human reality around us and encourages us in the greed and exploitation which creates the sector of poverty in the midst of wealth. Again we have deluded ourselves into believing the myth that Capitalism grew and prospered out of the protestant ethic of hard word and sacrifice. The fact is that Capitalism was build on the exploitation and suffering of black slaves and continues to thrive on the exploitation of the poor—both black and white, both here and abroad. . .The way to end poverty is to end the exploitation of the poor.

That’s the kind of analysis that made King so controversial in mainstream circles in his later years, and that has remained buried for the past 50 years under the exclusive focus on dreams and mountaintops.

Today, in Memphis and across the country, Americans would do well to remember the sanitation workers’ strike and the “radical redistribution of economic and political power,” as part of the new “era of revolution,” that King called for in launching the multiracial Poor People’s Campaign.

As Michael K. Honey puts it,

Remembering King’s unfinished fight for economic justice, broadly conceived, might help us to better understand the relevance of his legacy to us today. It might help us to realize that King’s moral discourse about the gap between the “haves and the have-nots” resulted from his role in the labor movement as well as in the civil rights movement.

In addition to remembering the eloquent man in a suit and tie at the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, we should also remember King as a man sometimes dressed in blue jeans marching on the streets and sitting in jail cells, or as an impassioned man rousing workers at union conventions and on union picket lines.