From David Ruccio No, the stock market is not predictable. And no one knows the exact causes of last week’s carnage on Wall Street—with the Dow down 4.2 percent, the S&P 4.1 percent and the Nasdaq 3.7 percent, representing their worst weekly performances since March. But the precipitous fall in all major indices, which many analysts blamed at least in part on the earnings blackout period, did serve to highlight one of the factors that has been driving the bull market: corporations purchasing their own stock. As Matt Phillips explained, When companies have more cash than they believe they can use productively, they typically return it to shareholders either with cash payments—known as dividends—or by repurchasing shares in the market. Buybacks raise demand, putting upward pressure on

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

No, the stock market is not predictable. And no one knows the exact causes of last week’s carnage on Wall Street—with the Dow down 4.2 percent, the S&P 4.1 percent and the Nasdaq 3.7 percent, representing their worst weekly performances since March.

But the precipitous fall in all major indices, which many analysts blamed at least in part on the earnings blackout period, did serve to highlight one of the factors that has been driving the bull market: corporations purchasing their own stock.

As Matt Phillips explained,

When companies have more cash than they believe they can use productively, they typically return it to shareholders either with cash payments—known as dividends—or by repurchasing shares in the market. Buybacks raise demand, putting upward pressure on share prices.

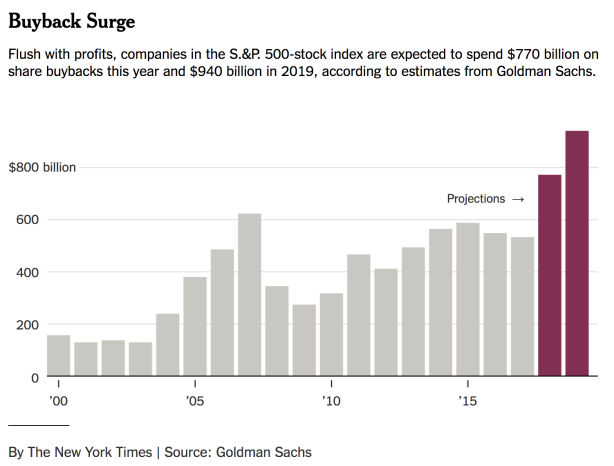

Such repurchases have boomed this year as the strong economy—and steep cuts in corporate tax rates—have left American companies flush with profits. Companies including Apple, Cisco Systems and Amgen have returned billions in cash to shareholders by buying back shares. Apple is responsible for the largest sum, spending nearly $64 billion on buybacks in the 12 months ending in June 2018, the last period for which full data is available, according to data from S&P Dow Jones Indices.

Generally, around earnings reporting season, corporations avoid repurchasing their own stocks, to avoid the charge of insider trading. But the overall trend is for U.S. corporations to spend (or to leverage, via debt) a large portion of their profits on buying their own stocks—with plans to spend $770 billion on share buybacks in 2018, and even more next year.*

And when they cut back on those purchases, as they seem to have done last week, a large part of the demand for stocks collapses.

The fact is, corporations have three major ways of goosing the golden goose, which they and a small group of wealthy households in the United States benefit from.

First, employers endeavor to keep workers’ wages low, even as productivity increases, thereby boosting their pretax profits (and then distributing portions of those profits in the form of salaries to their CEOs and dividends to stockowners).

Second, they lobby for tax breaks on corporate profits, an effort that once Donald Trump was elected delivered a slashing of the tax rate, from 35 percent to 21 percent.

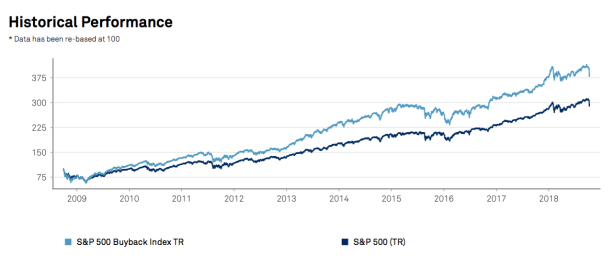

Third, they use a portion of those higher post-tax profits to purchase their own stocks, which tends to boost the price of shares, producing additional wealth for shareholders who hang onto their stock. It also improves per-share performance on key metrics like earnings, which in turn attracts more stock purchases from other institutional and noninstitutional investors with their own growing share of the surplus.**

The result, of course, is an increase in the already-obscene degree of income and wealth inequality in the United States.

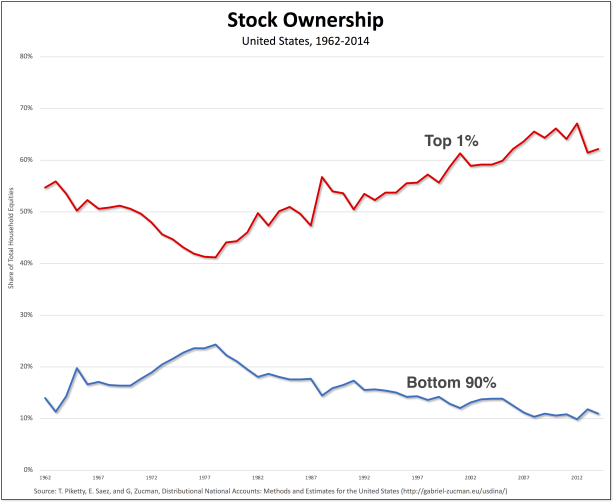

According to my calculations (illustrated in the chart above), the top 1 percent in the United States owns (as of 2014, the last year for which data are available) 62 percent of equities, while the share of the entire bottom 90 percent is only 11 percent.

So, it’s really only the small group at the top that is in a position to receive a cut of corporate profits in the form of dividends and to increase their wealth as corporate buybacks boost the prices of the stocks they keep in their portfolios.

Everyone else is forced to have the freedom to try to get by on their stagnant wages—and to watch in fascination and horror the ongoing spectacle in the Trump White House.

*For most of the twentieth century, stock buybacks were deemed illegal because they were thought to be a form of stock market manipulation. But since 1982, when they were essentially legalized by the Securities and Exchange Commission, buybacks have become perhaps the most popular financial engineering tool in the American corporate tool shed.

*According to the S&P Dow Jones Indices, the top 100 stocks with the highest buyback ratios in the S&P 500 have regularly outperformed the overall S&P 500 index (as seen in the chart below).